She liked to surprise me with these semi-impromptu trips.

The name called up images of the exotic and dangerous, and not just in old movies. My Uncle Douglas, my father's older brother, had told me about traveling to Hong Kong many years ago, flying from San Francisco on one of the huge Pan American Airways' flying boats, stopping at Honolulu, Midway island, and other strategic points across the Pacific for refueling, splashing belly first in the water with each landing and taking off in great waves of white spray. This was the old Hong Kong, before all the towers had started to rise, dramatically changing both the skyline and the nature of the city. He never wanted to return, he said, because he knew that this wonderful, magical place had been spoiled by development.

"I wandered through tiny alleys," he told me, "beggars following me, men offering me fantastic deals and sometimes their sisters, but it was beautiful, too, the green hills rising from the harbor, the blue water crowded with little wood boats and islands. No skyscrapers."

I was only a kid, so I asked him if—since he was there just after World War Two—spies were creeping around the city, too. He smiled and shrugged.

"Who knows? Maybe."

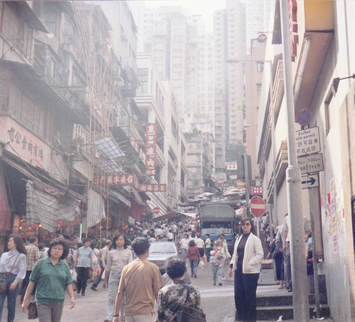

Sherrill on a Hong Kong street, 1990

Sherrill on a Hong Kong street, 1990

"Then you have to get some clothes, too. How about some dresses?"

Neither of us wanted to take the time to do it, so we left the bustling area of shops and hotels and made a trip to "The Land Between" along the border with China, a very different part of Hong Kong than we'd seen up to then, a land of green hills, terraced fields, duck farms, and rural markets. We might have been going back in time, back to the Hong Kong that my Uncle Douglas had remembered.

We tried to laugh in an understated way.

"Okay, but it won't be like the movies, you know."

A jetfoil carried us to Macau amid sprays of white water. When we started looking around the old Portuguese colony, we were surprised at how rundown and sleazy a lot of it seemed to be—just like in the old movies. Some of the buildings, in fact, appeared abandoned and in danger of collapsing. We looked into a couple of the casinos and gambling dens, but the air in them was so thick with tobacco smoke that we quickly backed out. And no sign of either Robert Mitchum or Jane Russell.

Sherrill. Temple of Makok, Macau

Sherrill. Temple of Makok, Macau The part of Macau that we liked best, though, was down in the heart of the old city where we asked one of the fortune tellers about our futures (he looked worried when he gazed at our palms, but for an extra tip promised that all would be good) and where we discovered a smelly concentration of tiny factories and workshops and watched people carving wood chests, putting together iron bedsteads, beating out aluminum bowls, stamping out toy soldiers, making noodles, painting wooden shoes, and pounding and blending medicines. Sherrill bought a folded paper package of herbal medicine, but I don't remember what it was supposed to cure. It looked pretty disgusting, though. I don't know if she ever used any of it.

Bruce, Pak Tai Temple, Cheung Chau Island

Bruce, Pak Tai Temple, Cheung Chau Island We were aware that in the time we had we could see very little of the dense, complex reality that was Hong Kong, but hoped, unlike my uncle, to go back one day—however, as it turned out, we never made it.

Back home in Berkeley, someone asked Sherrill if she wasn't afraid when we were lost among the crowds of Hong Kong.

"Are you kidding?" she replied. "I work in downtown Oakland. A man was shot to death on the library's front steps. A few weeks later, there was a gang killing in the McDonald's two blocks away. Hong Kong felt completely safe."

To be continued....

RSS Feed

RSS Feed