Sherrill's Iran Visa Photo

Sherrill's Iran Visa Photo He read it, grinning broadly. Crowds of children and some adults waved as we left, smiling and calling, "Goodbye! Goodbye!"

"Where are you from?" one girl peering out from under her scarf asked Sherrill.

"America."

"Welcome," the girl said, with a shy smile, and turned to pass the information to her companions.

In Tehran, we saw that a good half of the drivers were women.

"More than fifty percent of college graduates are women," we were told. "And more than half of the doctors. Many more women are educated, now, than under the shah."

We also discovered that every hotel room included a Koran, a prayer rug, and a small prayer stone on which to place the forehead while praying, and on every room ceiling an arrow pointed toward Mecca. One evening, we had dinner at a restaurant in a converted 15th century hammam: lamb kabobs, salad, and saffron rice, but no wine or beer or other alcohol. A few of us tried a nonalcoholic beer made in Iran. It didn't taste much like real beer, but was better than local soft drinks.

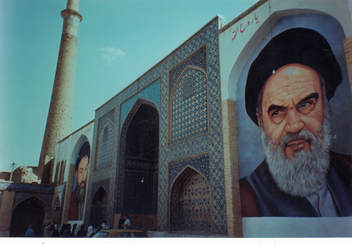

Mosque & Minaret with Portraits of Ayatollah Khomeini & Islam Revolution Martyr

Mosque & Minaret with Portraits of Ayatollah Khomeini & Islam Revolution Martyr "No wonder the people overthrew the shah," we couldn't help whispering to each other, as we trudged past the glass cases.

An early morning flight on an old Aerflot plane with notices in both Russian and Farsi took us past the snow-topped Alborz mountains to the holy city of Mashad near the Afghanistan border. At the airport, the men were publically frisked, while the women disappeared into a curtained booth. In Mashad, we drove directly to the holy complex, the resting place of the eighth Shi'ite Imam. Twenty million pilgrims traveled to his shrine every year. We could take photographs of the golden domes only from far away. Before we reached the shrine and surrounding buildings, our guide gave the women in our group chadors to cover their manteaus and scarves.

We weren't allowed to carry anything into the complex, not even a purse or camera. In our stocking feet, we were escorted through a series of courtyards, but couldn't go into the holy sanctuary, itself. The obvious devotion of the families and students around us, people even weeping, was touching, although foreign to us.

Tufa-carved Village of Kandovan

Tufa-carved Village of Kandovan A second guide joined us for a while. As we continued driving south the next day, he sang verses of Ferdowsi's poems, accompanying himself on a daf, a traditional goat skin instrument—a cross between a drum and a tambourine. His voice was strong, flexible, fluid.

"I was a music student at the time of the Islamic Revolution," he told us, "but after the revolution music was banned as too frivolous. Now, traditional Iranian music is allowed again."

"They should know better than to plant roses here," Sherrill said. "I feel sorry for the poor things."

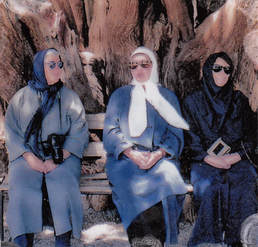

Sherrill (center) & Traveling Friends

Sherrill (center) & Traveling Friends One of the older men, with a short white beard and large dark brows, shuffled over to Hala and our guide, bowed slightly, asked several questions in Farsi, then bowed again and, belly leading the way, scuffed back across the linoleum to his companions.

"What did he ask?" Sherrill asked our guide.

"Where you're from," he explained, "and if you're Moslem. When I said no, you're not, he asked why the women are covered up, then. I told him that it was to show respect. That pleased him. I'm sure he told the others."

Sherrill at restaurant in former hammam

Sherrill at restaurant in former hammam Another day, we drove through naked hills and low mountains toward the Turkmenistan border, following the ancient caravan route of the Silk Road, along which a series of caravansaries had been built. No billboards spoiled the view along the roads. (Even in the cities there were few. The only large posters we saw in most towns were portraits of either religious leaders or young men killed during the Iran-Iraq war.)

In Royal Caravansary

In Royal Caravansary Afterwards, our guide explained that we'd been watching an historic sport in what was called a "House of Strength." In 1220 AD, the Mongols invaded Iran, destroying cities and towns. By decree, no Iranian male could carry weapons or train for war, but boys secretly were trained through sports so they'd be ready for war when the time came—spiritual and mental training, as well as physical. Now, House of Strength teams in many towns compete against each other.

A flight from Mashad to the city of Kerman and then, the next day, a bus trip across a hilly desert took us to the ancient walled city of Bam. The temperature outside had climbed to 100, heat radiating off the road so fiercely that we wouldn't have been surprised if it had melted into black goo, but still the women had to wear their manteaus, trousers, and head scarves. Even in our hotel room, if Sherrill took off the outfit she had to put it back on before she opened the door. A couple of days before, using her manicure scissors, she cut out the coat's lining, trying to make it more bearable.

Then we saw the 2,000 year old city in the distance, its huge crenellated walls and towers against the blue sky giving it the look of a giant dragon marching across the sun-baked hill. Eventually, with our bottles of water, we hiked through the giant mud-brick gate and along the narrow streets of the walled city, trying to stay in the shade. Drinking our water, we climbed past empty mud-brick mosques and shops, the remains of communal baths and houses, and up to the citadel at the top of the hill.

It seemed as if malicious gods were destroying the history of the world. Palmyra and other glories of Syria had been devastated, the great Buddha in Afghanistan was gone, and now Bam. This time the cause wasn't human viciousness, but that was small comfort. All across the Middle East and around the world, historic treasures and their record of human achievement were at risk.

Sherrill in carpet store, Iran

Sherrill in carpet store, Iran Kerman's magnificent mosque and fabulous bazaar were just two of many unique, historic places in Iran that are part of a global heritage we all share, wherever we happen to live, and for which we all are responsible.

To be continued....

If you find these posts interesting, why not explore the rest of my website, too? Just click on the buttons at the top of the page and discover where they take you—including to several complete short stories and excerpts from my novels.

Please pass the posts on to anybody else you think might enjoy them.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed