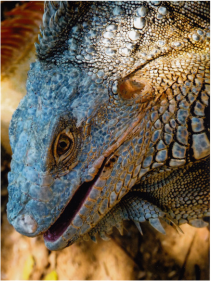

Finally, we drifted to a stop beside a cluster of small brown figures, most of them clinging to red-eyed iguanas. Instantly, barefoot children swarmed around us. The tallest girl, scraps of blue and yellow yarn braided into her black hair, slapped at the passenger door, her iguana grimacing. Dragging their beasts, the other kids gathered around her.

"Candy?" she demanded, using the English word.

"Candy!" they all hollered. “Pens! Money!”

They knew that much English, at least.

I didn’t know if I should give these children candy or money or anything else, or if that would encourage them to spend their lives begging. What about school? Since then, I’ve seen this in many places around the world. And in many developing countries grown men and women leave their fields and jobs to make and sell trinkets to tourists. Their ancient traditions and ceremonies are becoming entertainment for tourists. As we rush around “seeing” the world we’re having more impact than we may realize. Societies and cultures that until recently have survived almost untouched for generations and even centuries are changing, sometimes dramatically—and this probably is only the beginning.

Across the globe in Eastern India, we bounced and lurched for hours over narrow, crumbling roads to a remote forest village, an area of tribal people who still live as they did hundreds of years ago. The women of the tribe were unmistakable: small, dark brown, they wore their fortunes on their bodies, starting with large twisted metal rings around their necks and huge brass earrings. Their shaved heads were covered with coiled strands of small beads so that they seemed to be wearing colorful, close-fitting hats.

They used to be entirely naked except for their ornaments, but now they wore pieces of cloth around their waists and sometimes short capes. Their almost naked, flat chests were covered with strands of beads, with bits of glass and small seashells, that reached to below their waists. Bracelets of multicolored beads decorated their skinny arms and ankles. Very few men from any tribe were visible here. As with many tribal societies, the women of these remote Indian villages did most of the work.

Now, these women surround visitors from around the world, offering for sale the beads and jewelry that cover their bodies. Six foot-tall blond Norwegians bend over them bargaining for the trinkets that are their fortune. American women take photographs with mobile phones, offering small coins or candy bars as reward. Even this remote tribe may eventually become part of the modern world. It may give them more options in their lives and make life easier for them. Or will they come to prefer junk food to fresh fruit and vegetables? Will they start making these cheap trinkets specifically to sell to tourists, even adapt them to sell more? Will they want canned entertainment that has nothing to do with their own experiences? Are the old ways worse, better, or just different?

Are the people of this tribe happy? They’ve never known anything else, until now. Even though I didn’t buy any trinkets or snap any photos, I felt guilty for invading their ancient, rustic world, for leaving my footprint on this dusty path.

(Photo by Mona Reeva)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed