Sherrill & Bruce, 40th Wedding Anniversary, Eastern Turkey

Sherrill & Bruce, 40th Wedding Anniversary, Eastern Turkey We noticed what looked like a party in progress next to a faded blue house set back from the road. A group of men and women were dancing in a wide circle to recorded folk music on an open area between the house and road. We stopped and Hala and our driver walked over to find out what was happening. It turned out to be an engagement party for a young Kurdish couple—and we were invited.

Kurdish engagement party, Eastern Turkey

Kurdish engagement party, Eastern Turkey "Where are you from?" one asked. When we said the United States they were surprised, but pleased. They offered us fruit juice and sweets, then pulled us into the dancing circles. Laughing, we all did our best to copy the steps.

Kurdish engagement party: bride & groom, bride's sister & baby niece

Kurdish engagement party: bride & groom, bride's sister & baby niece "What was that?" I asked.

"A U.S. airbase is near here," someone explained. "The border is just over there."

Sherrill and I dropped out of the circle, but a young man came up and, with his few words of English, invited us to follow him into the house. The engaged couple was inside, sitting with family members in a low-ceilinged room carpeted with overlapping rugs. Very young, the boy and girl gazed up at us, the bride in a long white gown with high collar and full sleeves, the thin young groom, with hollow cheeks, dark eyes, and big ears, in an ill-fitting black suit. Were they as terrified of the future as they appeared?

"Please," I asked the man who took us in, "tell them that we wish them happiness and good fortune." Then, hand over my heart, I bent toward them and backed away.

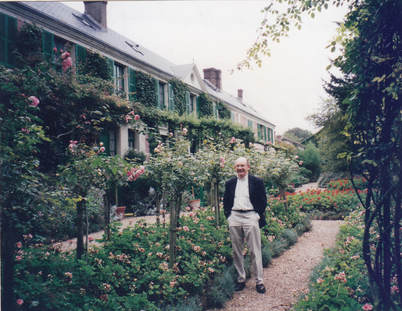

Our close friend and travel mentor, Hala, Topkapi Palace, Istabul

Our close friend and travel mentor, Hala, Topkapi Palace, Istabul From Trabzon, we drove east along a narrow coastal strip between green mountains and the sea, then turned inland until we drove along a fast-running river at the bottom of a deep gorge, tall cliffs on each side. Our goal was the Sumela Manastriri, an ancient monastery famous for its frescoes. Eventually, we parked and began a climb on foot up a steep trail of dirt, broken rock, and boulders until we reached a stone staircase of 90 steps and then saw the monastery complex rising like an organic part of the massive cliff face. Then, we descended and walked across the various levels of the ancient buildings, studying early frescoes depicting the life of Mary and various saints. Although damaged, the paintings powerfully dramatized the beliefs of the artists.

Village boy, Eastern Turkey mountains

Village boy, Eastern Turkey mountains  Rural life, Eastern Turkey, 2004

Rural life, Eastern Turkey, 2004 Sherrill and I celebrated the day of our wedding exactly forty years before with a party our good friend Hala gave us with our group in the lounge of our hotel in the historic border town of Kars. We even were treated to a stirring performance of young costumed, sword-flourishing, Armenian dancers: a memorable celebration with good friends in an exciting place.

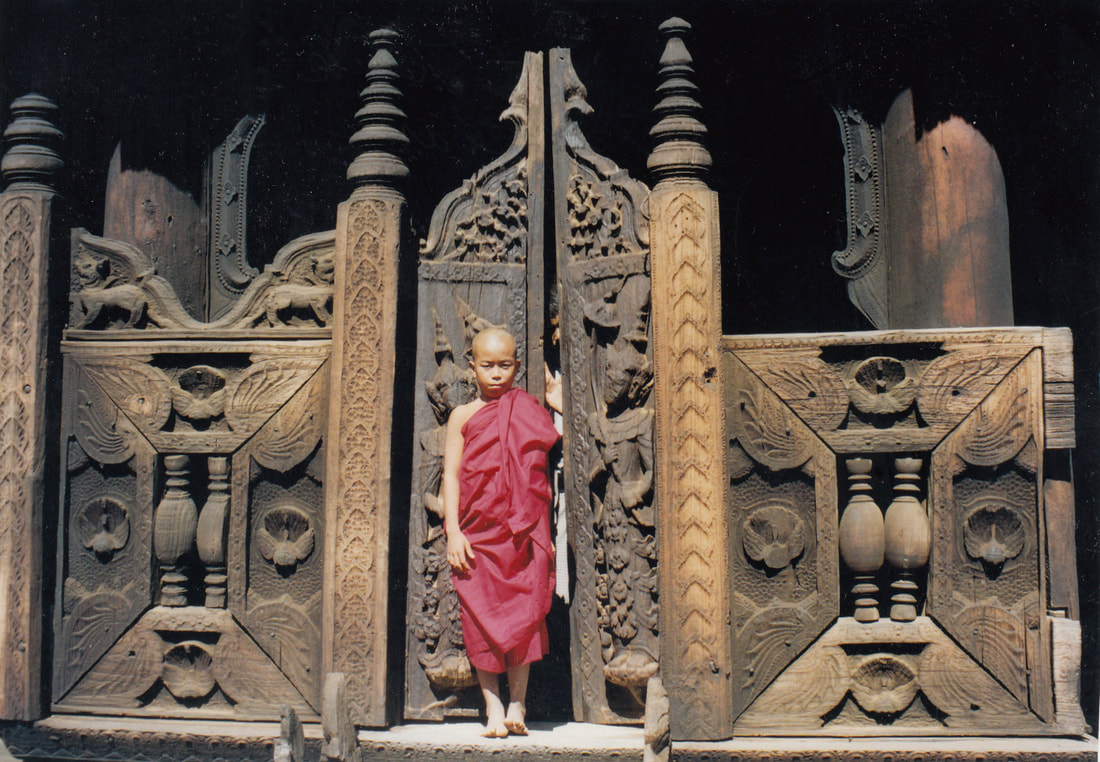

Ferry boat captain's son, en route to Akdamar Island, Eastern Turkey

Ferry boat captain's son, en route to Akdamar Island, Eastern Turkey The next morning, a small two-deck boat took us to the island of Akdamar in Lake Van. The captain's son, a boy of about eight, never stopped working, coiling and uncoiling ropes, moving ladders, serving drinks, passing out napkins, carrying sugar for tea, moving fearlessly up and down the steep outside stairs as the boat churned through the lake waters.

Armenian church, 915 AD, Akdamar Island, Lake Van

Armenian church, 915 AD, Akdamar Island, Lake Van So much of Eastern Turkey is mountainous and rocky, we had to wonder why people fought over it for so many centuries. The university town of Bitlis, named after one of Alexander the Great's commanders, was another vertical city, streets and neighborhoods climbing treacherously steep cliffs. Here, as all over Eastern Turkey, 90 percent of the people on the street were men, the few women trudging along the dusty streets under their heavy bundles, completely covered. The cafes, Sherrill noted, were filled with men sitting on low stools, smoking, talking, and sipping small glasses of tea.

Sherrill and great tower, Hosap Kalesi Citadel, 1643

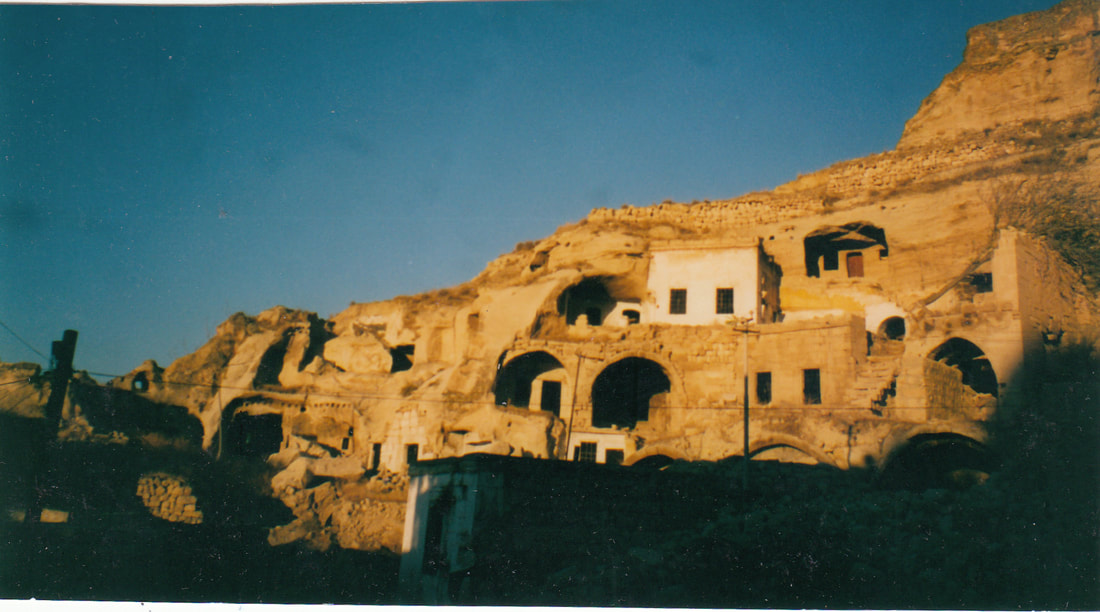

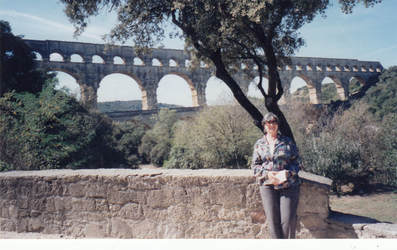

Sherrill and great tower, Hosap Kalesi Citadel, 1643  Mud brick beehive houses in 4,000 year-old town of Harran, where Abraham lived

Mud brick beehive houses in 4,000 year-old town of Harran, where Abraham lived The Biblical Abraham was said to have lived in the ancient village of Harran around 2000 B.C. Large mounds called tels were scattered around the village and as far away as Syria, all of them the remains of prehistoric settlements. We climbed the huge Harran Mound, or tel, many layers of history dating back at least to the third millennium B.C. beneath our feet. We almost could feel the layers of history underfoot, stories waiting to be told: tales of the Iron Age, Pagan, Jewish, and Moslem stories, perhaps Christian stories, as well. Harran and environs is said to be the first place in the world to build with adobe mud brick. About 1,000 of the traditional mud brick beehive houses survived. We visited one, four connecting beehive-roofed rooms, cool inside, despite the heat outside.

Bruce standing by heads from decapitated colossal statues, Mt. Nemrut

Bruce standing by heads from decapitated colossal statues, Mt. Nemrut Finally, we reached a small parking lot below the summit, from which we could walk up. A few people elected to ride donkeys. Later, Sherrill told me that her donkey driver spoke enough English to tell her that he supported a wife and five children with his job. Half way up to the summit, she heard an odd ringing sound. His cell phone. Although the donkey stopped while he took the call, when Hala and I reached the summit on foot there was Sherrill, sitting on the stone steps leading to the altar on the Eastern Terrance, staring at the great stone heads that had been placed in front of the monumental statues from which they'd fallen—the king and the gods, including Hercules and Apollo.

Sherrill & Bruce at mountain rest stop, Eastern Turkey

Sherrill & Bruce at mountain rest stop, Eastern Turkey "She is under my protection," he said—a very Moslem/Middle Eastern way of expressing the situation, I thought.

The plane from Gaziantep in the east to Istanbul was crowded, but the flight was smooth and from the air we could see how empty and rugged much of Turkey still was. The next morning, we were up early for our flight to Ankara, the capital of the country and much closer to Cappadocia, our next destination. First, we visited the State Archeology Museum in a large Ottoman-era building. Ranging from prehistoric to Neolithic to Hittite and more, the collection gave a breath-taking picture of early Turkish history, even pieces from the 8th century B.C. burial treasure of King Midas--and his skull.

Forty years and still counting!

Forty years and still counting! By the time we landed in Istanbul, the city glowed with electric lights. After a few days on our own in the city, Sherrill and I flew back to San Francisco, but we promised ourselves that we'd return. Three visits simply weren't enough. That didn't happen, but we always remembered Turkey and Istanbul as among our favorite places.

Please pass the posts on to anybody else you think might enjoy them.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed