Simone & Sherrill & friend, in Yucatan

Simone & Sherrill & friend, in Yucatan Part way through the job, a cloud of reddish dust announced a rusty pickup truck with half a dozen workmen on the open bed behind the driver. Several of them had the sleek Mayan profiles we'd seen in museums and carved on temples. When they saw me behind the car, tools in hand, they laughed and hooted and called out in rapid Spanish. For one irrational moment, I pictured these dust-covered men jumping out of the old truck to rob us, but they waved cheerfully, amused by the sight of me struggling with the tire, and bounced and lurched on their way. I finished with the tire (after chasing a lug nut into the undergrowth) and Sherrill started along the road again. Five minutes later, a huge bug blew in the open window, stung me below my right eye, and flew out again. The side of my face soon swelled up into a painful red balloon.

"What a morning!" I grumbled, suppressing several other expressions that came to mind, but that wasn't all the fates had for us that day.

Simone at Palenque, Yucatan

Simone at Palenque, Yucatan Several dripping boys waded up to us, shouting, finally making me understand that the road ahead was closed—the bridge was out. They pointed to a detour. I gave them a tip and we went the direction they said, hoping for the best. Eventually, we realized that we'd reached the town of Campeche on the Gulf—very different than it is today, mostly un-restored, not yet a big tourist destination, despite its colonial history. As far as we were concerned, its glory was a hotel where we could escape the storm and recuperate from the day.

The next morning, the storm had passed, the day was clear and hot (and humid), and—with a new tire and my swollen cheek—we continued on, visiting pre-Columbian ruins, starting with the Zapotec site of Mitla. Its geometric friezes, carvings, and mosaics seemed so crisp and perfect that whoever made them might have just stepped out for a lunch break. Chitzchen Itza and Uxmal were just as impressive in different ways, all of them home to hairy tarantulas, giant red ants, and scorpions. It was hard for us to believe that Mayan priests—and their sacrificial victims—were able to climb those steep narrow steps to the tops of those huge pyramids. Simone and I climbed part way a few times, but that was enough for us.

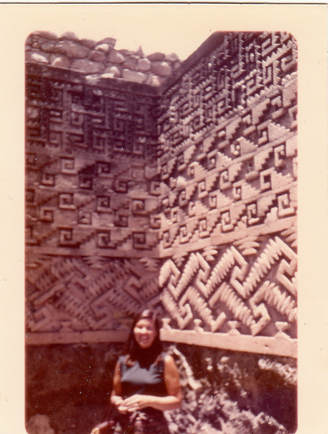

Sherrill at Mitla, Yucatan

Sherrill at Mitla, Yucatan Despite its renegade atmosphere—or maybe because of it—Veracruz's central plaza was surprisingly busy in the evening. Ignoring the heat and humidity, families and couples crowded the restaurants under arches along the sides, cigar-smoking old men played dominos in front of the colonial-era city hall, and friends and lovers strolled around the square. Today, this city founded by Hernan Cortes has a reputation for being one of the most dangerous in Mexico, but in 1972 we felt safe. More than anything else, we felt the pull of history.

The cathedral with its tile-covered cupola had survived centuries of sun and storm, revolution and war, even earthquakes. Now it faced a row of electric-light-draped arches under which purple- and orange-skinned people swatted insects and stuffed spicy food into the dark O's of their mouths. Mustachioed waiters in stained white coats bustled between tables, trays balanced on splattered shoulders. Peddlers hustled in and out of shadows, shoving necklaces and postcards at diners. Crusty-nosed kids hardly three-feet high juggled boxes of Chiclets over plates of mole. Long-skirted women, babies hidden in rebozo folds, dangled beads and braided leather belts between German tourists and their plates.

Under one of those arches, Sherrill and I ate snapper veracruzana while Simone slowly spooned her flan. We talked and ate and watched the passing scene—the cheapest show in town—until she fell asleep at the table, using her napkin for a pillow. I carried her clutching it to our hotel room and brought it back the next day.

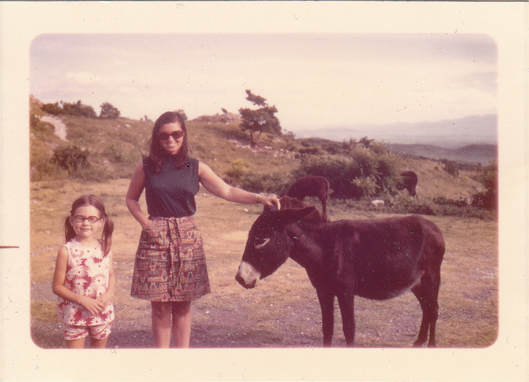

Sherrill & Simone, Merida, Yucatan

Sherrill & Simone, Merida, Yucatan "Where is your other child?" The officer aimed his handsome brown face with its thick black eyebrows and moustache at Sherrill. The three of us were at the Mexico City airport, about to leave—we hoped—for San Francisco. Sherrill looked at him, not clear what he meant. "You each have a child on your entry form," he explained.

"When we came into Mexico," she said, "at the train station in Mexicali—they said we both had to put our daughter's name on the forms."

"We only have one child," I pointed out. "Look, it's the same name. Simone."

The officer looked at the forms and at Simone.

"But where's the other one? You can't leave him in Mexico."

"This is our only child named Simone and it's a girl. Here she is."

We'd forgotten that in Latin countries boys can be named Simone, too. The officer seemed to be afraid that we were trying to abandon our son in his country. Eventually, we did seem to persuade him that we only had one child and she was in front of him. He stamped our papers and let us go to the airplane—all three of us—but I wasn't sure that he was entirely convinced about how many kids we had.

Sometime later, at home, we got a letter telling us to go to the San Francisco airport to pick up a package. It turned out to be our missing camera—with the film still in it. How it happened, we never knew.

To be continued....

If you enjoy these posts, why not explore the rest of my website, too? Just click on the buttons at the top of the page and discover where they take you—including to several complete short stories and excerpts from my novels. Please share the posts with anyone else you think also will find them interesting.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed