Sherrill, Havana, Cuba

Sherrill, Havana, Cuba Havana, 2003: an old city, a hot and humid city in which bare skin was in fashion, a city rich with art and music. We were there in a small group of eight with our friend Hala, who had arranged for us to visit in a special cultural program—an exception to the ban then on U.S. citizens going to Cuba. At the airport in Miami we'd been warned not to lose our letter of permission from the U.S. government or we'd each have to pay an eight thousand dollar fine. After an hour flight, we stepped down a rolling staircase to the Havana runway. As soon as we walked out of the airport we came face to face with a 1948 Studebaker, the model with the pointed jet airplane grill in front.

Old Havana

Old Havana The next day, a drive to Revolutionary Square gave us views of a monument to the national hero Jose Marti and a giant portrait of Che Guevara on the side of a large building. Nearby, we saw a yellow sign with large black letters on a wall: "La Verdad sobre el BLOQUEO debe ser conocida." Somebody translated it for us: "The truth about the blockade must be known."

"Blockade?" I asked.

"It's what Cubans call the U.S. Embargo."

"And what is the truth?"

"It's also called 'genocide' here."

In a cafe where we stopped for lunch, an old man with a guitar appeared in the doorway as we ate a blockade "salad" of canned corn and canned peas. He was followed by a skinny youth shaking a pair of castanets, both of them singing. Their complicated salsa rhythms filled the air.

"Music," we were told, "is one way to survive."

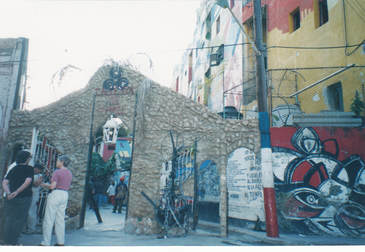

Callejon de Hammel, Havana

Callejon de Hammel, Havana "Callejon de Hammel, a street of art, a celebration of Afro-Cuban culture. Most of it relates to Santeria."

"The cult?"

"More than that. A religion, a way of life. Mix primitive Christian beliefs with West African gods worshiped by sugar plantation slaves, add rum and cigar smoke. Result: Santeria. Drums and rhythmic movement send you into a trance so you can communicate with your ancestors and their gods."

In a gallery, we discovered images and figures representing Yoruba/Santeria gods.

"There is Oshun, the river goddess, Chango's favorite wife. Chango evolved from the Yoruba god of thunder. Oshun was the blood that created human life—also Our Lady of Charity. Two gods for the price of one, just as Chango also is St. Barbara, because they're both fond of hatchets. The Santeria gods have both African and Catholic identities. Gender is irrelevant."

All of this came together for us in a weathered colonial building in an old Havana neighborhood. In the once grand house, we sat on folding chairs to watch brightly costumed dancers. Chango led the way, followed by Eleggua, the teasing god, performed by a boyish young woman in motley costume, who pranced and leaped, sat on audience members' laps, snatched scarves or hats, then returned them to the wrong people, tossing back her head with silent laughter. Then female dancers in green, white, and red dresses pranced and whirled, seducing bare-chested men who arched over them with erotic abandon.

Havana balcony scene

Havana balcony scene Leaving at the end of the show, Sherrill pointed up to an open window where a caramel-skinned girl not more than nine or ten in a white dress with a red bow in her black hair was swaying to the music pouring into the street. Then, looking across the street, we saw painted on a wall beneath an old apartment building the red letters: "VIVA FIDEL."

Sugar cane plantation, Cuba

Sugar cane plantation, Cuba  Sherrill, sugar cane plantation

Sherrill, sugar cane plantation The infamous Hotel Nacional, built in 1930, became popular with Americans during the last years of Prohibition and during the gangster era after. Before long, it was the Havana headquarters of the Mafia. We were there one evening for a reunion concert of Cuban jazz greats, primarily from the "Buena Vista Social Club." The hotel walls were covered with photographs of celebrities who had stayed there, including movie stars like Errol Flynn and Frank Sinatra, politicians, and gangsters—including Mafia king Meyer Lansky. Most of the band members were in their twenties and thirties, but the old timers were in their seventies and eighties. As soon as they heard the applause as they came out, though, they seemed to swell up with new energy. Sherrill, who used to play the clarinet and saxophone in bands, was impressed with their skill and energy at their ages.

Hemingway's home, near Havana

Hemingway's home, near Havana "Are you Canadian?" he asked me. "I heard you speaking English."

Sherrill gave me her "you've been talking too loudly again" look, but he was just curious about where we were from and was astounded when I admitted that all eight of us were from the U.S. He and his wife, he said, were from Czechoslovakia. He was even more amazed when I told him that Sherrill and I had visited his country in 1988.

"But you're Americans!" he gasped. And the whole world knows, he implied, that Americans don't care about anyplace outside of their own little sphere.

Standing there, we talked for a while about travel and America and making friends in different countries. Before we left the dining room, he again vigorously pumped my hand.

Sherrill, banana orchard

Sherrill, banana orchard  Block party in Remedios old town

Block party in Remedios old town "Your wife is a very nice lady," one of the young people told me.

Sherrill & Bruce, Santiago de Cuba

Sherrill & Bruce, Santiago de Cuba  Central Plaza, Santiago de Cuba

Central Plaza, Santiago de Cuba "Buenas Noches," I told her, picked up my money, and went to the bar to pay for my drink.

The U.S. embargo, however, had affected Cuba's ability to get and maintain medical equipment. Cuba's clinics and hospitals could buy equipment from Japan, Sweden, Australia, and other countries, but couldn't get replacement parts from the U.S. If a U.S. company bought a company in another country or even had a relationship with a company trading with Cuba, the Cuban medical facilities no longer could get machines or parts from them. As a result, Cuba focused on keeping the population healthy through prevention programs.

Che Guevara statue, Santa Clara, Cuba

Che Guevara statue, Santa Clara, Cuba  Political Art, 2003 Bienal exhibition, Havana, Cuba

Political Art, 2003 Bienal exhibition, Havana, Cuba To be continued....

Please pass the posts on to anybody else you think might enjoy them.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed