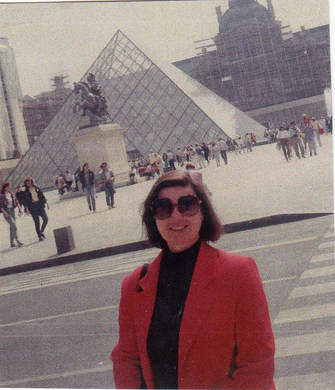

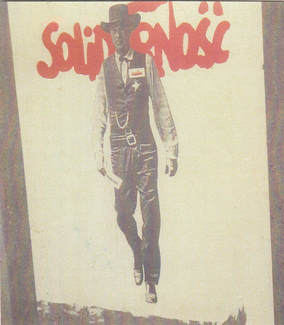

Sherrill, Paris, start of Pilgrimage route

Sherrill, Paris, start of Pilgrimage route "Of course."

It would be fascinating, Sherrill convinced me, to travel the same ancient roads that the faithful trekked a thousand years ago. And why did they do this? Because they'd been told that if they prayed to the remains of saints preserved in the churches and abbeys along the route they'd be saved from the horrors of eternal damnation, which they believed in quite literally. We didn't want to either walk or pray, but did want to see the Romanesque churches and the often spectacular reliquaries that held the bits and pieces of the saints. The pilgrimage routes crisscrossed much of Europe, but the ones that interested us the most led from Paris to the great church of Santiago de Compostela in Spain.

Sherrill, ever resourceful, found a small group tour led by a pair of married professors that would follow one of those pilgrimage routes. As it turned out, the group was just five, plus the husband and wife profs, and, although we traveled in a van, often we felt as if we'd ridden a time machine back to a feudal world.

We flew on TWA (soon to be extinct, although we didn't know it) to Paris, where we started our pilgrimage—as many of the original pilgrims did—at the Sainte-Chapelle on the Ile de la Cite', where the actual Crown of Thorns reputedly had ended up. The light, I remember, seemed particularly beautiful that day, pouring through the sixteen colored glass windows of Sainte-Chapelle onto our little band of travelers. The walls around us might have been prisms capturing all the light in the universe.

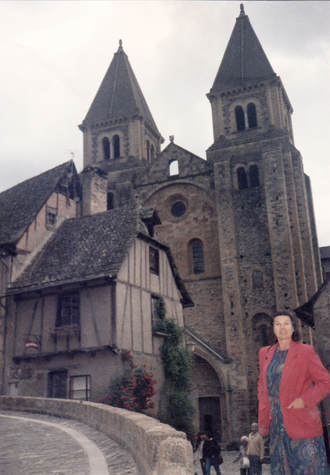

Bruce & Sherrill, France, en route to Santiago

Bruce & Sherrill, France, en route to Santiago She was right: the Church of the Middle Ages delighted in showing the horrible punishments waiting for the damned. The Last Judgment carvings on the cathedral at our next stop in Autun were even more violent, with vast numbers of the damned being clawed, chewed on, and pulled apart by demons. As we traveled from one church to another, we developed a new appreciation for the wicked imaginations and great craftsmanship of medieval sculptors. Only the saints, it seemed, were worthy of sympathy and respect.

Sherrill was eager to visit the great abbey at Cluny, the world's largest and richest church until St. Peter's in Rome was built, and also famous for once housing the most important manuscript library in Europe. Most of the abbey, however, was destroyed during the French Revolution and the surviving manuscripts scattered. Only one of its eight great towers still stood, but its remains were impressive, even so.

Bruce, Romanesque Church, Vezelay

Bruce, Romanesque Church, Vezelay  Sherrill, Conques Village & Church, France

Sherrill, Conques Village & Church, France Wouldn't it be nice to live here, where it's unspoiled and full of history? I asked Sherrill as we wandered through Conques.

"There you go again," she said. "You're such a romantic. Maybe the people here don't love it so much and would like to get away, but can't afford it."

"I still think it's beautiful."

She patted me on the back. "Never mind."

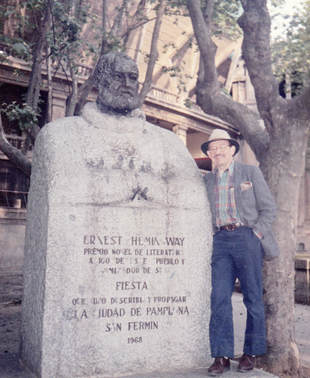

Bruce, Pamplona, Spain, Hemingway Monument, by Bull Ring

Bruce, Pamplona, Spain, Hemingway Monument, by Bull Ring Finally, we drove into the Pyrenees and through the historic pass where the French pilgrimage routes crossed into Spain, where we stopped at Pamplona, famous now, of course, for the annual running of the bulls and The Sun Also Rises.

That first evening, since we'd been riding much of the day, Sherrill and I decided to go for a stroll. Our hotel stood isolated on a triangular island bordered by busy streets, the new city across one and the old city across another. In the newer part of town, a few blocks away, we came to the bull ring and a rectangular monument topped with Ernest Hemingway's bearded head. Eventually, we wandered over to the older, more picturesque city, where we were surprised to discover large piles of garbage, broken furniture, and even mattresses, piled on corners at the intersections.

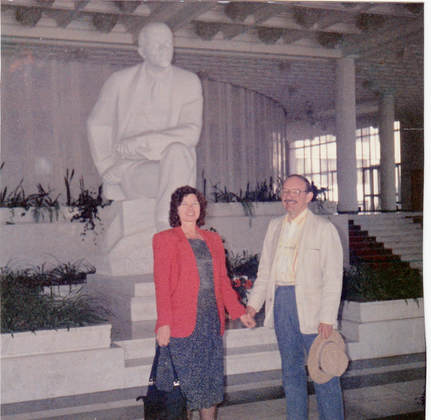

Sherrill, Visigoth Church, Spain

Sherrill, Visigoth Church, Spain While staying in Burgos, we went out each evening to join the paseo, when families, couples, and groups (especially teenagers) strolled along the sidewalks and pedestrian streets, shopping, gossiping, flirting, and then, when the hour was late enough, stopping someplace to dine. We saw no cars trying to "drag main," such we'd seen in California when we were young, just this tradition that engaged the whole community from babies to grandparents and probably great grandparents.

Sherrill at Church of Santiago de Compostela, Spain

Sherrill at Church of Santiago de Compostela, Spain To be continued....

You also might enjoy reading the new bargain-priced e-book of my novel, The Night Action. It has been called the last great novel of an past era. "The novel careens around the night spots of San Francisco's North Beach and the words seem to fly off the page in the style of Tom Wolfe or the lyrics of Tom Waits." The book is available at Amazon and Barnes and Noble. Click on the title for the link. Or click HERE.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed