Although we'd talked about saving places relatively close to home for when we were 'old,' we'd already taken mini-trips to see fall foliage in New England and to explore various cities, including Las Vegas, Chicago, Portland, and Seattle, but she was thinking of something more ambitious. As usual, she had a specific adventure in mind.

Sherrill, Cathy, Bruce, Larry, Canyonlands National Park

Sherrill, Cathy, Bruce, Larry, Canyonlands National Park The next morning, we set off with a local guide and her group to the old Mormon town of Moab, gateway to the red rock world of Arches and Canyonlands National Parks, a land of deep canyons, tall mesas and buttes, and landscapes eroded into fabulous, unexpected shapes. It even was possible that we'd stumble over petrified dinosaur tracks. In a Moab pub I bought a bottle of Polygamy Porter, which on its label asked "Why have just one?" Clearly, Utah now was less strict about alcohol than we remembered.

Canyonlands National Park

Canyonlands National Park "Herds of wild horses once roamed here," our guide told us. "Close your eyes and you'll hear their hooves."

That evening, overwhelmed by this endless grandeur, we were treated to a "cowboy" barbeque dinner cooked in Dutch ovens and then a boat ride on the Colorado River through an illuminated red rock canyon. We agreed that it was hokey, but fun, and when the artificial lights were turned off the black sky above the canyon walls exploded with stars.

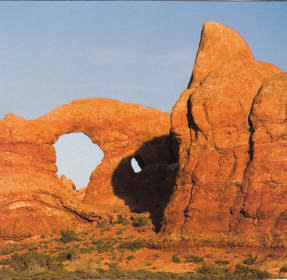

Arches National Park, Utah

Arches National Park, Utah "Nobody will believe it, otherwise."

Our appreciation of the absurd had helped bring us together decades before and it still was alive and kicking.

During lunch, we started talking with some of the other members of the group, including a middle-aged couple originally from Bangalore, where Sherrill and I once had quite a different kind of adventure.

Arches National Park

Arches National Park Decades earlier, the U.S. military conducted secret above-ground atom bomb tests in a remote area of southern Nevada at the Utah border. Fallout from the tests blew across the rocky desert and several towns, causing dramatic increases of different types of cancer in the population, especially in children. In 1956, a John Wayne/ Susan Hayward epic was filmed in the desert there. By the end of 1980, 91 of the cast and crew had developed cancer and 46, including Hayward and director Dick Powell, had died of it. The red rocks and desert were beautiful, but were they still deadly?

Back in Moab, we visited a museum of local history that took us from the dinosaurs up to the John Ford western movies made there, then we dropped in on a few art galleries. After our long day of hiking over rocky trails and Moab pavement, we relaxed in a local dive, "Eddie McStiff's," with drinks and then dinner. Of course, I had another bottle of Polygamy Porter.

"Don't get addicted to that," Sherrill warned me.

"Too late!"

Cathy, Larry, Sherrill, Bruce at the Four Corners

Cathy, Larry, Sherrill, Bruce at the Four Corners "Well, we're here!" Sherrill pointed out.

There was no denying that we were there.

The lady from Bangalore (now from San Diego), short and somewhat plump, but very charming, had learned that I was a writer and approached me across one of the state lines with questions, her dark eyes bright with polite curiosity. She belonged to a book club, she said, and loved to read and made me give her the names of my books. Months later, I got a note from her that she had read one.

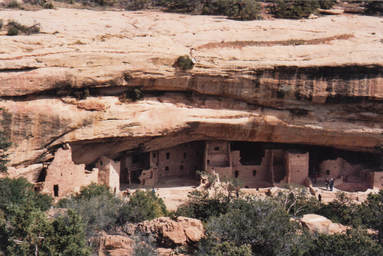

Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado, a UNESCO World Heritage Site

Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado, a UNESCO World Heritage Site The site, he said, had been left to crumble until the Civilian Conservation Corps that President Roosevelt established during the Depression set to work on it.

"They saved Mesa Verde," he stated, looking around at all of us. "And now President Obama's stimulation package is saving it again. Over the years, it had been ignored and allowed to fall into disrepair, but now it will last for future generations to discover and enjoy."

Spruce Tree House, Mesa Verde

Spruce Tree House, Mesa Verde Then, as we followed the white-haired guide up the steep sandstone steps to "Spruce Tree House," he segued into the story of the native Americans who lived and flourished there for more than seven hundred years. "Archaeologists called them the Anasazi, but today we call them Ancestral Puebloans." When the house was discovered in 1888, a large Douglas spruce was growing in front of it. Although the tree is long gone, he explained, the name stuck to it.

* * *

Durango-Silverton narrow gauge train, Colorado

Durango-Silverton narrow gauge train, Colorado "Don't look," Sherrill told me, as the train shook and rattled, swerving around sharp cliff-top curves above a rushing river. I started to protest, but she added, "And don't fuss, Wart." Her abbreviated nickname for her "Worry Wart."

"I can't imagine anyone building these tracks," I told Sherrill, gazing out at the tops of trees.

"Be glad that you didn't have to."

"I am!"

Cathy & Larry, History Museum, Santa Fe, New Mexico

Cathy & Larry, History Museum, Santa Fe, New Mexico This was the address of, as a plaque now read, "The Santa Fe office of the Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory." The little storefront office was the place from which the people who worked on the atom bomb at Los Alamos left on their way to the project—the place from which they disappeared. They went in the front door and left by a secret back door to an alley and waiting vehicles.

The plaque continued: "All the men and women who made the first atomic bomb passed through this portal to their secret mission at Los Alamos. Their creation in 27 months of the weapons that ended World War II was one of the greatest scientific achievements of all time."

Cathy & Sherrill with long horn goat, Santa Fe

Cathy & Sherrill with long horn goat, Santa Fe

To be continued....

If you find these posts interesting, why not explore the rest of my website, too? Just click on the buttons at the top of the page and discover where they take you—including a bio, information about my four novels, along with excerpts from them, and several complete short stories.

Please pass the posts on to anybody else you think might enjoy them.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed