Sherrill and Bruce with robot friend who, oddly enough,

seemed to be the mascot at Runnymede,

where the Best of English Gardens tour began.

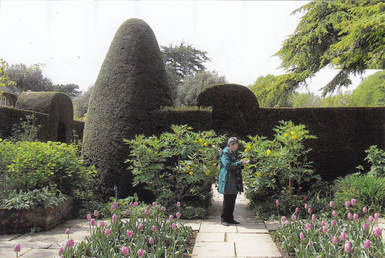

Sherrill, on the Best of English Gardens tour, 2015

Sherrill, on the Best of English Gardens tour, 2015 As she gained strength after this year-long ordeal, she discovered a Best of English Gardens tour that she wanted to do to celebrate her recovery: visiting some of the most famous and iconic gardens of England, ending with the annual Chelsea Flower Show in London. Her oncologist said that there was no reason why she shouldn't take the trip.

"I can do this," she told me, as we packed. "Don't worry."

Sherrill's favorite gardens, the ones most congenial to her, were the deceptively casual-appearing gardens of England, with their planted "rooms" of different colors and textures and their herbaceous borders that offered unexpected delights to the eye. This was the style that had influenced Sherrill when she designed and created her own garden in Berkeley.

Sherrill in hidden nook, Fenton House garden, Hampstead, London

Sherrill in hidden nook, Fenton House garden, Hampstead, London Gardens, I think, gave Sherrill hope. These living, growing, places of beauty promised that there would be a future. Seeds would germinate, plants would grow, flowers would blossom. They attracted and nurtured birds, butterflies, and bees. The tour visited many of the most famous and influential English gardens, ranging from very personal ones such as Wendy Dare's little hillside terraces next to an old Gloustershire mill to the large, formal, gardens of Stourhead in Wiltshire and Hidcote Manor in the Cotswolds to the eccentricities of writer Vita Sackville-West's garden rambling among the ruins of a castle.

We allowed ourselves time in London, both before and after the tour, to visit other gardens in the vicinity, as well. A short trip on the Underground took us to Hampstead, where we walked up a curving hillside road to Fenton House, a 17th century red brick National Trust mansion with a terraced walled garden, topiary shrubs and trees, sunken garden, and rose garden.

"I've seen this before," Sherrill said as she sat on a bench beneath a purple wisteria on the upper terrace, looking toward the house.

Then we both remembered where: The gardens had been one of the locations in a BBC miniseries about a 1930s jazz band, Dancing on the Edge. It projected the posh yet stylish atmosphere needed for the scene.

Sherrill, Eccleston Square greenhouse, London

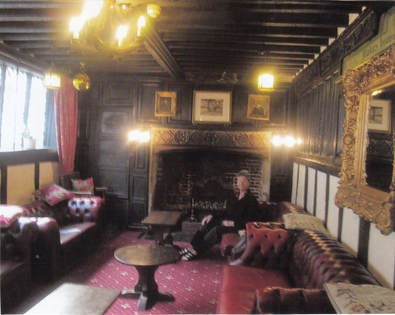

Sherrill, Eccleston Square greenhouse, London  Barnsley House, Cirencester, Cotswolds

Barnsley House, Cirencester, Cotswolds Rosemary Verey was a formidable name among serious gardeners, so Sherrill was pleased when we began with gardens that Verey designed in the 1950s for the 17th century manor, Barnsley House. Following the paths leading from the mansion, we discovered lawns framed by topiary plantings, herbaceous borders in full bloom, knot gardens, a laburnum walk, and ornamental fruit and vegetable gardens, each section rich with gorgeous, sometimes whimsical, surprises.

Of course, Sherrill pulled out her notebook and pen and began jotting down ideas. She soon made friends with other gardeners on the tour, especially a woman from Massachusetts who had two homes with gardens and a landscape gardener from Grass Valley in northern California.

"Every terrace, large or small, every path and step, all the plantings and beds. We weren't rich, so we couldn't hire it done, but we loved doing it."

"Sounds familiar," Sherrill smiled.

* * *

"He was influenced by Gertrude Jekyll," she reminded me, with tap of her notebook on my shoulder.

To a gardener, that was like saying he was influenced by Leonardo or Rembrandt.

"You're not making notes, now," I mentioned to Sherrill.

"Nothing here inspires me."

Once again, Sherrill didn't bother to make notes.

* * *

Sissinghurst gardens from the Tower

Sissinghurst gardens from the Tower Novelist and gardener, Vita Sackville-West, with her diplomat husband, Harold Nicolson, created a unique world when they transformed the ruins of a fortified manor house into their personal retreat and garden.

Climbing to the top of the sixteenth century tower, we could see the garden's various "rooms"— the "white garden" and other beds with spring blossoms opening, tulips, bluebells, wisteria, roses, azaleas, and more. Our garden didn't have a moat to cope with, as Vita famously wrote about in one of her gardening books, but Sherrill did pick up some ideas from the planting arrangements and color combinations. Maybe the most important lesson was to be fearless. If something doesn't work, change it.

Sherrill particularly had wanted to see Great Dixter, a 15th century house and garden to which gardeners from around the world made pilgrimages. She'd read the books by Christopher Lloyd, who'd spent more than 40 years transforming the garden, experimenting with ideas about plant combinations, colors, scale, and texture. Although she didn't always agree with his theories, she'd incorporated some of his ideas into our garden—especially about herbaceous borders.

"They really should be called masala borders," Sherrill said, with twinkle, using the Hindu word meaning "a mixture."

Back in London, we spent most of a day at the Royal Horticultural Society's Flower Show in Chelsea. The day before, the Queen had officially opened it and the next day it would be opened to the general public. Some people had dressed up for the occasion, as if they were going to the Ascot races, others not so much. Although there were a number of large indoor pavilions, the big garden displays that competed for prizes were outside. The grand prize went to a garden sponsored by the Chatsworth Manor estate.

Chelsea Flower Show exhibit of garden statues

Chelsea Flower Show exhibit of garden statues However, she did collect a number of ideas from the display gardens. This was the end of our tour, so the next day the two of us took a train to the coastal town of Rye, which she had wanted to see for a long time, particularly Lamb House and garden, where Henry James had lived for several years. The Chelsea Flower Show wore her out, so a train ride was a chance to rest.

Sherrill in Rye restaurant

Sherrill in Rye restaurant "I love this," Sherrill whispered, squeezing my arm.

"Maybe, if you call a place a garden," Sherrill said, staring at the human-sized cats frolicking on the grass, "it is."

Two more days in London took us to William Morris's Red House at Blexleyheath and Kensington Palace and Gardens, all enjoyable, but we were ready go home. It had been a good trip, even though a lot of it was a challenge for Sherrill. Nevertheless, as the weeks and months went by, we started making plans for more trips and good times together.

If you find these posts interesting, why not explore the rest of my website, too? Just click on the buttons at the top of the page and discover where they take you—including a bio, information about my four novels, along with excerpts from them, and several complete short stories.

Please pass the posts on to anybody else you think might enjoy them.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed