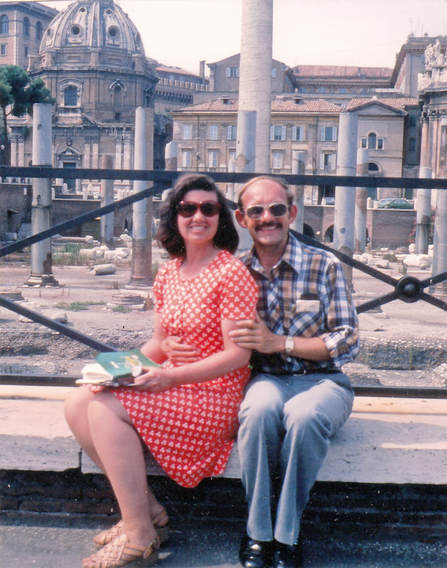

Sherrill & Bruce in Rome

Sherrill & Bruce in Rome Rome is a city for walking, despite its hills, and we walked! Coping stoically with tired feet, Sherrill, Simone, and I discovered the endless variety that is Rome. To fight the summer heat, we consumed gelato—much gelato. Especially from a wonderful little place near the Piazza Navona. Then, flourishing more clippings, Sherrill explained how easy it would be to get to the Renaissance gardens of the Villa d'Este, so from Rome's Tiburtina station, we rode a local train to Tivoli so we could walk even more among its fountains, statues, and grottos. This local train was pretty much like the others we'd experienced, but we were starting feel that they were quaint and even charming.

As spectacular as the acres of decorated walls, cleverly shaped hedges and trees, antique statues, and reflecting pools were and as imaginative as the spouting fountains were, Tivoli wasn't quite what we'd expected. We didn't doubt that the place deserved its reputation and designation as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. It certainly was unique, but was it a "garden?" Most of it wasn't what Sherrill thought of as a garden, but more of a triumph of architecture and "hardscaping."

"I'm glad I saw it," she sighed, "but give me an English garden, any time."

Simone at Tivoli Gardens

Simone at Tivoli Gardens Rome's massive train station, designed under Mussolini, but built after the war, promised speed and efficiency. Despite the early hour, we were looking forward to riding the new super express Aurora, which was to get us to Naples in just two hours. However, it never appeared. Then we learned that a strike had derailed it. As time went by, we began to wonder if we'd just stay longer in Rome and miss Naples and Pompeii.

"Everything has been too easy," I moaned. "This is our punishment."

However, we discovered that a later, slow, train heading to Sicily would pass through Naples. Apparently, it wasn't affected by the strike. Too unimportant, maybe. Two hours later, we were on an old, battered train heading south. Five hours and many stops later, we arrived in Naples. Each time the train stopped, some kind of altercation exploded on the platform beside it, giving us visions of being stranded in a village between Rome and Naples, but eventually it staggered on its way again.

A local train on Naples' suburban train system took us to Pompeii—well, toward Pompeii. From time to time, it stopped. Not a strike, somebody told us, just a work slowdown. Wonderful, we thought. How many days would we be stuck among these hills and farms? At least, we had a snack with us. Eventually, we did walk among the remains of Pompeii—until we had to catch the train back to Naples. We didn't want to stay there all night, among the ghosts of Vesuvius's victims.

Capri is paradise on earth. At least, that seems to be what most people think. At last, we were going to find out for ourselves. Running to the dock in Naples, we jumped onto a crowded ferry just before it pulled away—avoiding a two hour wait for the next one. After bouncing around for a while in the blue water, it deposited us and more than a hundred others us near a rocky beach crowded with exposed skin. Vendors were selling gelato and cold drinks and funny little toys.

The streets of Venice may be water, but we ended up with tired feet, anyway. We'd reserved a room at the Pensione Accademia, the little hotel on a small canal just off the Grand Canal used by the secretary heroine in the movie Summertime. Jane Hudson learned in Venice that reality may not live up to dreams, but that doesn't mean it's better never to dream. We got lost among the canals, narrow streets, and winding alleys, but enjoyed that even more than the museums and galleries.

"Mit goulash," I read on signs in front of some restaurants. And "Mit Schlog."

We were surprised to see so many signs catering to German tourists—some entirely in German. Clearly, Europe had moved on since the War.

The pigeons at Piazza San Marco rivaled the numbers at Trafalgar Square, but folks didn't feed them as generously as in London. Variegated feathers brushing past our hot faces, we settled at a table in front of a cafe and I started to read aloud from the guidebook.

"Not now," Sherrill protested. "Just sit here and enjoy it."

After resting on the piazza, sipping overpriced bottled water, we boated out to the Lido so we could rest more on the beach. Another day, we rode a crowded vaporetto to the island of Murano, where, as wide-eyed as any other tourist, we gazed at the ancient and magical process of creating sparkling, fragile glass from fire. Sweaty faces flushed from the heat of the furnaces, the craftsmen demonstrated their astonishing skills, using thin tubes, lung power, and deftly maneuvered implements.

To save money, we brought a picnic with us on the long-distance train to Paris on the first part of our trip back to London. Across the aisle, an elegant French woman glanced disapprovingly at us as we devoured it. The only other movement I saw her make was to slip the heel of her foot out of one of her two-tone pumps. Twice. Several hours later, though, hungry again, we hiked through the train to the dining car. We ate well, but when the time came to pay, I found myself counting paper bills in three different currencies into the waiter's hand. He smiled, but converted the pounds and lira into francs until he had enough.

On our way to Heathrow, before leaving London we stopped to see the crown jewels at the Tower. Since there was no place to check our suitcases, we carried them with us. One of the guards opened and searched them—to Sherrill's embarrassment.

"Don't worry, love," the grinning middle-aged guard told her as he pawed through her underwear. "We're all married men here!"

There was no mistaking that we were Americans—sometimes loud and messy, sometimes trying too hard to be friendly, but curious and interested in everything. Looking back, I like to think that we didn't do so badly.

To be continued....

If you enjoy these posts, please share them with anyone else you think also will find them interesting.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed