Dinner with friends

Dinner with friends "We haven't really started yet," we sometimes replied with a shrug and a smile. The more we traveled, the more we wanted to do it. I sometimes wonder if we were trying to catch up with ourselves—past and future, too. Motion isn't only through space, after all, but through time, as well: our time and the times we live in, the past but also the future, as it becomes present and past. As we traveled, it blurred together. And, sometimes, even just a day with friends could feel like a trip to another place and time, leaving us rich with memories.

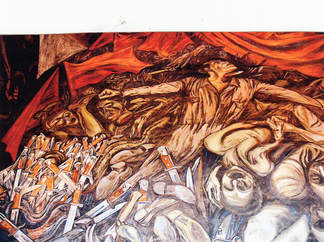

One reason Sherrill and I were drawn to the Mexican muralists, I suspect, was because they didn't compromise. Their art hurled truth as they saw it right in our faces. The past, we learned early in our travels, is more than a colorful theme park—and nowhere is that more evident than in Orozco's murals. In building after building, we found walls and ceilings covered with his fiery paintings of human suffering and the struggle to escape it—and along the way, we also were immersed in the beauty of Guadalajara.

The next year, the three of us returned to England—and to Stonehenge, since Simone had little memory of walking among the giant stones when she was three. While we were in the area, we stopped at the broken monoliths of Avebury Circle, some Neolithic burial mounds, and recently excavated remains of ancient Roman villas—mostly mosaic floors and outlines of walls, but evocative of past times and lives, nevertheless. We also discovered some medieval stone farm buildings in remarkably perfect condition. We almost could smell the farm animals and the sweat of long ago farm hands.

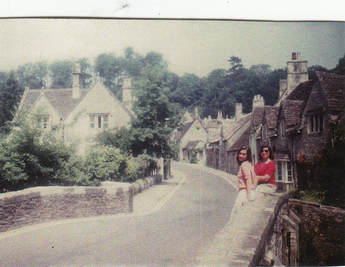

Driving through the fertile green hills and farms of the Cotswolds, we were tempted to stop and use all of our film (people still used film then) on one picture-perfect country scene after another. The golden stone buildings of Castle Combe and the other Cotswold villages seemed to glow as if lit from inside when sunlight hit them. On the outskirts of one village, we stopped to watch men re-thatch a cottage roof, doing it as their ancestors would have five hundred years before.

Sherrill & Simone in Bath

Sherrill & Simone in Bath As we traveled over the years we saw how people everywhere work to create something that will last after they're gone. The men thatching that roof could point to it later—as their children and grandkids would be able to in the future. A thatched roof can last fifty or more years. The carpenters and stonemasons who built the manor houses, churches, and castles were leaving part of themselves behind. Why did Walter Potter devote his life to stuffing those tiny animals and arranging them as he did? Why did Orozco hurl himself into the backbreaking effort of covering walls and ceilings with his vision of life and death?

Similarly, I also remember the times when adults, even into middle age, came up to Sherrill in stores and on the street and in libraries to introduce themselves.

"Mrs. Reeves? You don't remember me, but my mother brought me to your preschool story hours. I loved those times. Because of you, I learned to love books. Thank you."

The words varied, but the message was always the same.

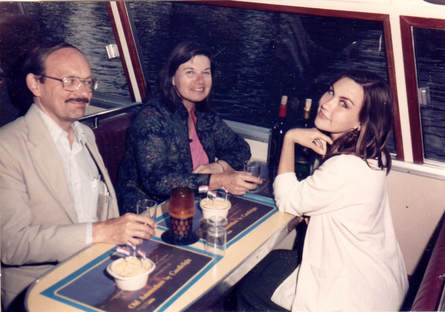

Bruce, Sherrill, Simone on Amsterdam Canal Boat

Bruce, Sherrill, Simone on Amsterdam Canal Boat * * *

Across the English Channel in the low countries, we found a vivid, colorful world, one in which people were happy to talk with us and help us. Even then, most of them seemed to be fluent in English. Amsterdam was where we first ate in an Indonesian restaurant and indulged in rijsttafel, the "rice table" meal that we came to love. The bowls of rice with a dozen or more appetizer-size dishes of seafood, meats, vegetables, nuts and fruits, and more overwhelmed us at first, but how could we resist the tantalizing rainbow of sweet and spicy, salty and sour flavors?

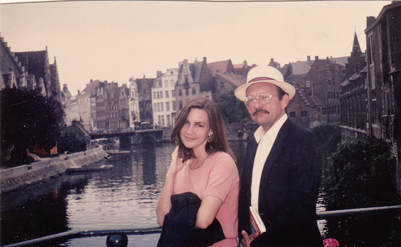

Simone & Bruce at Bruges

Simone & Bruce at Bruges Sherrill loved boats of all kinds, so when we could we explored Amsterdam, Bruges, and other cities on their canals, passing narrow old houses (including one the width of a single window) with their steeply peaked roofs. One of those gaunt Amsterdam houses was where Anne Frank and her family hid during the Nazi occupation. We read about such terrible times, but nothing brings them to life as vividly as being in the place where they happened. Standing in those small, cramped spaces, we wondered why the family didn't lose their sanity and why it took as long as it did for them to be discovered. Anne Frank's diary ensured that what she and her family suffered would not be forgotten.

Simone in Ghent

Simone in Ghent Traveling, I think, taught us to appreciate the moment, maybe because we knew that we'd be moving on. Maybe, without realizing it, sometimes we were happy and sad at the same time. We could appreciate simultaneously the beauty of Orozco's work and the horror it represented or see the beauty of ruined abbeys and Greek temples and at the same time the fact that the worlds they were from were long gone. Later, we were to see on television and in newspapers the destruction and loss of places we'd learned to love, such as Syria and parts of Iran and Italy and Southeast Asia, whether because of human beings or natural causes. We didn't dwell on the sadness, but increasingly became aware of it.

To be continued....

RSS Feed

RSS Feed