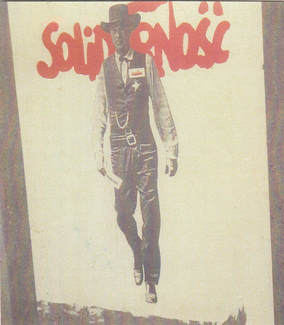

Sherrill, Warsaw, Poland

Sherrill, Warsaw, Poland We couldn't travel there independently because all trips had to be organized and controlled by the Soviet Intourist agency, but Sherrill discovered a British company that was working with Intourist. This would be a chance to get farther behind the Iron Curtain, she pointed out, even if we couldn't push it aside, ourselves.

"They have no taste," Sherrill whispered to me. "How could they not know how ugly this place is?"

"Worse than that," I countered, peering over her shoulder around the dusty acreage of the lobby, past the fake leather chairs at the middle-aged bellboys and clerks shuffling in the shadows, to the little hard currency shop in one of the corners. "I feel like I'm being watched all the time."

"You don't need to be paranoid, sweetie. Losing your mind right now is not a good idea."

Changing the Guard, East Berlin

Changing the Guard, East Berlin "If we're lucky, we'll get through in under an hour," she told us from the front of the bus, standing behind our diminutive Belgian driver, Cesar, as he steered the Mercedes coach through the erratic East Berlin traffic. "They go over the bus very carefully. Once, it took us two hours. They come on board, look at your passport and match the picture to you. Mostly, they'll search the bus to make sure no East German is doing a Houdini to escape to the Western zone. Cesar has been through this before." She peered through the wide front windows at the little house and gate of the Friedrichstrasse border crossing. "We have the big German woman," she announced. "Don't try to be friendly. It'll make her suspicious."

A uniformed guard rolled over a steel-framed mobile staircase and scrambled up to survey the top of the coach. Simultaneously, a large mirror was slid beneath so that another guard could inspect its underside. The humorless female guard, standing like a Wagnerian soprano in her uniform and heavy shoes, exchanged terse remarks with Marina, then plodded down the aisle, demanding passports. It seemed like a joke, but none of us dared smile. A third guard, with Cesar's assistance, was searching the engine section at the rear of the bus, luggage compartments on the sides, and even the cooler chest where drinks were kept. Finally, Brunhilde growled at Marina, who stepped down off the coach with her.

"You passed," Marina told us when she was back on the bus. "And Cesar and the bus passed," She looked at her watch, "Only forty-five minutes."

The bus paused after we were through so we could take pictures, then continued on, stopping at the Brandenburg Gate with the Wall—its skin a chaos of graffiti on this side—hiding part of it, and then at the burned remains of the Reichstag building, once the center of the German government, still not restored after many years. Eventually, we came to a boulevard lined with sleek new buildings, on one of which a Mercedes logo revolved. Cesar tucked the coach into a parking place between the Zoo train station and the Kurfurstendamm.

"I can't believe it!" Sherrill indicated a large group of German students at the museum.

It was true, though: they were excited about an exhibit of hand-woven baskets and other artifacts made by California Indians, identical to those we'd studied in grammar school.

* * *

Stalin's Tower, Warsaw, Poland

Stalin's Tower, Warsaw, Poland "It's considered the best address in Warsaw," Marina told us, "because then you don't have to look at it."

I remembered from movies made in Warsaw after World War II by Polish director Andrzej Wajda how devastated the city was, not a whole building left standing. Since then, the main square in the historic city had been reconstructed using old paintings and photographs as guides, but it looked as fake as a stage set. When we walked into a few of the buildings, we saw that their interiors had no relation to their exteriors. We stopped at the site of the notorious Warsaw Ghetto, where a huge monument had been built in 1948 to honor the Ghetto uprising of the Jewish partisans against the German military occupying the city. One side represented the heroic Jewish rebels, the other the tragic parade of Jewish families to their fate, one carrying a Torah.

A personable young woman in her late twenties, she understood that we weren't too happy and offered to take anyone who wanted to go with her on a walk that evening and chat with us. Sherrill and I and a few others decided that it had to be better than sitting around in that hotel. As we strolled on almost deserted streets, she answered questions about the lives that she and her friends led. Shortly before leaving home, Sherrill and I had watched one of the few new Soviet movies to get to the United States, Moscow Does Not Believe in Tears, which followed the lives and fortunes of three young women, their relations with men (all of whom turned out to be drunks), and their careers. Judging from this film, the life of a woman in the Soviet Union wasn't easy. Even the life of the most successful of the trio, who became an engineer, looked pretty Spartan to us—and that was after she dumped her abusive drunkard husband.

"Does the movie give an accurate picture of life over here?" I asked.

"Ah," she replied. "I love that movie. All my friends love it, too."

Another lesson from those long days on the road through the Soviet Union was that it was a very large sprawling, carelessly stitched together, quilt of a country.

"It's like driving over and over again across central Canada," Sherrill commented, "but not as exciting."

To be continued....

RSS Feed

RSS Feed