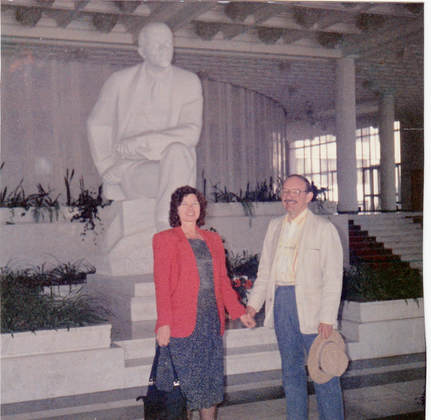

Sherrill & Bruce with Lenin at Hotel Yugo-Zapad, Moscow

Sherrill & Bruce with Lenin at Hotel Yugo-Zapad, Moscow Before we reached Moscow, Cesar stopped the coach at a roadside restaurant so our guide could call Intourist—pre-cell phones. We could see Marina through the window having an agitated conversation on the telephone. Finally, she returned to the bus. As Cesar drove on to Moscow, she explained what had happened.

"They wanted to put you in the Hotel Belgrade, an old dump. I've seen rats there! Finally, they agreed to another hotel, new and modern. Unfortunately, all the rooms are singles. That's because it's a convention center where the Party sends members for advanced training. It's very nice—even if husbands and wives will be in separate rooms."

During our free time, we took the Metro back and forth to the center of town, usually to Red Square or the picturesque Arbat neighborhood—the North Beach or Greenwich Village of Moscow. The stations—one of Stalin's better legacies—were amazingly grand and ornate, with arched, tiled ceilings, fancy columns, sculptured plasterwork, and terrifyingly deep and fast escalators. To avoid getting lost, since we couldn't read Cyrillic, we identified the names of the stations, counted the letters and memorized the first and last letters. Somehow, we survived and got where we wanted.

| Marina and the local Intourist guide showed us the usual sights, starting with Red Square and Lenin's embalmed body. "He looks like a Madame Tussaud wax figure," Sherrill whispered to me. It was true: he looked as if he was wearing makeup. Maybe that was why we weren't allowed to photograph him. Then we continued with St. Basil's cathedral, its bulgy, colorfully striped domes like a collection of giant candies, suggesting an oversized gingerbread house. Nearby, the austere Kremlin Walls with their notched crenellations and round towers, several topped with blood red ruby stars were appropriately foreboding. Marina pointed out the twin-towered red brick state history museum, which looked like a place where painful interrogations would take place. We couldn't go into the museum, but Marina assured us that it was boring and the local Intourist guide insisted that we had to go see the monument to Yuri Gagarin, the first human in space, back in 1961. The actual statue turned out to be surprisingly moving: a forty-two meter tall titanium column, ribbed to simulate rocket exhaust, with a stylized Gagarin at the top, arms raised, face lifted toward the stars. | On another day, we had some delightful hours at the Pushkin Museum, which had nothing to do with the poet, but was crowded with Western art, especially Impressionist paintings, much of it acquired at the end of World War II. We also were given tickets for an evening at the Bolshoi Theatre—folk dances that night, not the ballet. Several times, we passed yet another of those overly decorated, monstrous wedding cake towers so beloved by Stalin--even bigger and uglier than the one in Warsaw. When Sherrill and I went into the GUM "department store," we saw that it was more like a mall with separate shops than what we think of as a department store. The late-nineteenth century architecture, with three floors of open walkways running past the shops, a glass and iron roof arching above, was spectacular, but there wasn't much there to buy. Ordinary Russians seldom went there, anyway. "Never mind caviar and fur coats," Sherrill insisted. "I'd kill for a good salad or an avocado—even an orange." |

The henna-haired woman at this shop recited in broken English the Odyssey of her woes, no money, no fruit to sell most of the time and when she did get some it often was rotten, a lazy husband who usually was drunk on vodka, kids who ran off instead of helping her, and on and on. Finally, I bought a small bag of the apricots, overpaying her because I felt she'd earned it with her performance.

What did the principal want to do with the money? Buy things? But there wasn't much to buy in this country. Russian clothes? His were much better than any he could purchase here. How many cute Russian nesting dolls could he need? Did he simply like to shop?

"In Red Square!" Sherrill shook her head. "I never thought he was very bright, but holding up a bill like that in Red Square! Poor dope."

"It's the kid I feel sorry for."

Mile after mile of tall, slender birch trees flickered past under a sky of blinding clarity, the horizontal markings on their black and white bark leaping from one to another as we sped past on our way to the ancient walled city of Novgorod. We might have been in an old black and white Russian movie, fleeing the Czar's troops. From time to time, we glimpsed ornately painted wooden cottages and small villages among the trees. We crossed the mighty Volga and spent the night in Novgorod, our hotel on a hill, wedged among old wooden houses, some unpainted. We definitely had slipped into an Eisenstein movie, I told Sherrill.

"Don't get carried away," she warned me. "You haven't had dinner, yet."

The days were long, now, and the nights were over in moments, but that gave us more daylight to enjoy the splendors of Leningrad. The light seemed to glow on the many canals that sliced through the city and off the walls of the palaces above them, but it was hard for us to be sure of the time of day. We spent many happy and exhausting hours in the vast Hermitage palace museum, and even then couldn't see all the paintings and other treasures that we would've liked to have studied, and, of course, the palace, itself, was worth exploring.

"Can you believe it?"

Sherrill indicated the wide open windows, letting the gritty city air into the galleries where masterpieces from before the Renaissance to the Impressionists and after hung naked on the walls. In each large room, an old babushka sat on a chair in a corner, knitting or dozing, supposedly guarding the treasures around her, but not one of them would've noticed if we'd walked out with armloads of paintings—and what would they have done about it, anyway?

Sherrill, Peter & Paul Fortress, Leningrad

Sherrill, Peter & Paul Fortress, Leningrad "This is our heritage," the guide told us. "It is important for us to preserve it."

We were aware, now, as we toured Leningrad, of how much restoration work must have been here done after the War, although they didn't bother with Minsk and other cities we visited: street after street and canal after canal, lined with palaces and other buildings, including several palaces that Catherine gave one of her lovers, Count Potemkin.

In a small park across from our Leningrad hotel, stood one of the many monuments we saw throughout the Soviet Union to the Great Patriotic War, as they called World War II. One day, Sherrill and I noticed that a large crowd had gathered in the park. When we walked over to investigate, we discovered that a man was selling hundreds of pairs of white athletic socks from a suitcase to excited customers.

After several days in Leningrad, our group was treated to what Marina called a "farewell banquet." The meal was of many courses and nicely served, including one glass of sparkling Romanian wine for each of us and such delicacies as caviar, but the courses nevertheless were small.

The next day, Cesar and Marina drove us though another forest and across the border into Finland and its capital city, Helsinki. Passing the harbor on our way to our hotel, we were astonished to see a huge fruit and vegetable market: scores of tables piled high with produce, vegetables and fruit, strawberries even falling onto the pavement.

"Wait!" we called to Cesar. "Stop! We need to buy this stuff. Stop!"

To be continued....

If you enjoy these posts, please pass them on to anybody else you think might enjoy them. And why not explore the rest of my website, too? Just click on the buttons at the top of the page and discover where they take you—including to several complete short stories and excerpts from my novels.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed