Sherrill on the Yangtze River

Sherrill on the Yangtze River We climbed across several rotting wood docks, then up mossy concrete steps lined with mud-hued beggars, some missing arms, others legs, holding out tin cans tied to stumps, making weird noises in their mouths. Then we were guided to an ancient building and up and down a series of steps and through corridors and rooms displaying torture devices and scenes of "Hell." It seemed anticlimactic after the mutilated beggars on the steps.

Second Wu Gorge, Yangtze, 1993

Second Wu Gorge, Yangtze, 1993 Later in the day, the ship entered the first of the three great Yangtze gorges. Variegated with green streaks of lush vegetation, the gorge narrowed in places, cliffs rising steeply on both sides. Caves and oddly shaped outcroppings appeared high on the rocky cliffs, each with its own stories and legends, usually about monks, royalty, generals, and other historic or fictional figures. Some of the huge rocks had been given descriptive names.

At Wushan, we changed to a small motorized sampan for a side trip up the Daning River into three smaller gorges. These narrow, cliff-lined gorges hurtled upward with unexpected drama, even more than the big one we'd just seen. We entered the first Daning gorge under a graceful, high-arched automobile bridge.

"What about the people?" I asked.

"Necessary more than million being moved and towns and cities relocated."

"Then why do it?" Sherrill asked.

"China will have world's largest dam," he replied, proudly.

We were tempted to use all of our film on that first Daning gorge—the "Dragon Door" Gorge—because the cliffs were so tall and close, dripping with yellow-green foliage. On one side, endless rows of square holes penetrated the rock, all that was left of an amazing plank walkway constructed during the Han period: wooden stakes once were inserted into the holes to support planks from which peasant trackers pulled boats up river. These historic remnants also would be drowned.

The next Daning gorge was studded with jagged rocks and shadowy caves and the famous "hanging coffins" on the cliffs, where monks were placed when they died. Small clusters of people appeared from time to time on tiny beaches. Rick explained that they made their living collecting rocks from the edge of the river. They would be relocated when the dam was completed—to a city far from this river where their families had spent their lives for generations.

from the Daning River gorges, we returned to the great 25 mile-long middle Yangtze gorge, where the White Emperor was dwarfed by the sheer cliffs and peaks that rose startlingly against a steel gray sky far above. We might have been bobbing up and down in a toy boat.

"Aren't you glad we came now, instead of waiting?" Sherrill asked me.

Later that morning, we passed through a huge lock at the Gezhouba Dam, the first dam built on the river, back in the 1970s. The lock was so big that we shared it with the Yangtze Princess with room to spare. Talking from deck to deck, we learned that the VIPs who bumped us from that newer ship were a group of Taiwanese that the Communists wanted to impress.

The Yangtze suddenly spread out wider than before, the great cliffs left behind as broad green plains stretched out on either side. The ancient town of Jingzhou, although we'd never heard of it before, surprised us in odd, conflicting ways. We were impressed by the Han era treasures in its museum, especially the preserved corpse of a Han lord and 2,000 year old lacquer ware and silk clothing, but the stores in the town had almost no merchandise, just empty boxes and plastic bags piled on the dusty aisles and stairs. Clerks stood around gossiping, ignoring both the mess and the few customers, reminding us of stores we saw in the Soviet Union.

"Obviously, they don't care," Sherrill said loudly, "if they sell a single piece of that garbage." Not one turned to look at her.

Our experience with the Yangtze should have ended in Wuhan, but instead of getting there by ship, we now took an alarming six hour bus ride through small towns and past farms and new "industrial zones," the driver leaning on his horn the whole time. The two-lane highway was a chaos of constantly passing vehicles—buses, trucks, cars, wagons, bicycles, motorbikes, and an erratic stream of pedestrians—but we saw only one accident, a minibus-truck collision.

"In China, when vehicles collide," Rick told us, "people say they kissed."

We suspected that on Chinese roads there was plenty of vehicle smooching.

Bruce, Shanghai, 1993

Bruce, Shanghai, 1993 Trying to navigate Shanghai's streets in the morning, I discovered one day, was a struggle with torrents of people on foot and on bicycles and pushing on and off buses. A few blocks from our hotel I was horrified to see another of those awesomely ugly buildings constructed across the Communist world by Uncle Joe Stalin, the Shanghai Exhibition Center, a huge horseshoe-shaped tower splotched with Mayan/Egyptian/Babylonian decorations. Inside, the merchandise seemed intended only for gullible tourists. No sane Chinese would waste money on any of it.

That evening, Rick took us through the city to the Shanghai Acrobatic Circus on Nanjing Road. Along the way, he pointed out the architecture of the different foreign concessions, or districts, of the past—some distinctly French, others British or German. Since we were there, most of those historic districts have been replaced with new towers. The city didn't have many high-rises yet in 1993, but it had smeared plenty of gaudy, multi-colored neon, or sometimes strings of colored lights, over the old buildings.

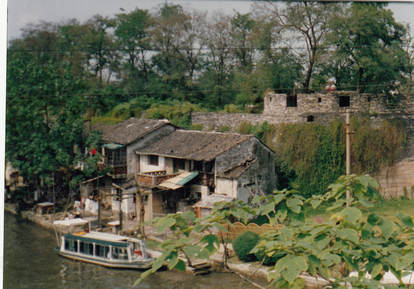

Suzhou Canal

Suzhou Canal Constantly changing views, ranging from water buffalo trudging through flooded rice fields to the steadily coughing chimneys of power plants to chaotic scenes of new construction, kept us staring out the window.

"I love this," Sherrill grinned, watching the passing scenes. "It's almost like being on a boat."

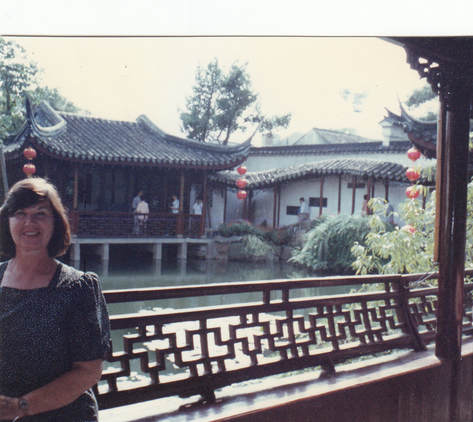

Sherrill, Suzhou Garden

Sherrill, Suzhou Garden During the next two days, Rick seemed under pressure to make sure that we followed the official itinerary, taking us to a silk factory, an embroidery factory, a paper cutting workshop, and a sandal wood factory. Of course, we had opportunities at each place to buy treasures to carry home. A temple and a museum were squeezed in along the way, each of which also boasted a gift shop.

Suddenly, the Bund, historic business center on the waterfront, once part of the International Settlement, opened up before us. Now, we could stroll along the street without being shoved and pushed, admiring the old buildings, the broad esplanade, the white ships at anchor, the bridges and monuments against the blue sky—cities in China then still could have blue skies. The buildings that once housed foreign banks and trading houses, famous cafes and bars and hotels, still stood, suggesting a romantic past, now gone forever. Only on the other side of the river were new towers starting to rise. Foot sore, we stopped for tea at the former Cathay Hotel, now the Peace Hotel, then indulged in a taxi across town to our hotel.

"They expect bribes, now," one said, "the bigger the better."

However, we had only to see the huge line of people waiting to see Mao in his Beijing mausoleum to know that the country still had strong ties to Communist ideology. The image that especially stuck with me, though, was that of a young man in a blue suit riding in Beijing traffic on his bicycle while talking intently into his cell phone. What, Sherrill and I wondered, would China be like when all the ambitious young entrepreneurs like this one traded in their bikes for their own BMWs?

To be continued....

You also might enjoy reading the new bargain-priced e-book of my first novel, The Night Action. Set in San Francisco's North Beach, it has been called "the last great novel of an past era." The book is available at Amazon, Barnes and Noble, and other retailers. Click on the title or Here for the link.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed