"We've never been there," Sherrill answered.

"And it'll be a trip back in time," I added. "Way back...."

Sherrill, ready for adventure, with driver in Jordan

Sherrill, ready for adventure, with driver in Jordan "After thirty years," she exulted, "it's about time!"

The security routine at London's Heathrow airport where we boarded the Royal Jordanian plane for Amman was unlike anything we'd experienced. This was long before 9/11 and the enhanced security that followed. Our hand baggage was x-rayed several times and I was frisked at least two or three times and an electronic wand was used over Sherrill more than once. We wondered if somebody knew something we didn't, then decided that even if they did we didn't want to know.

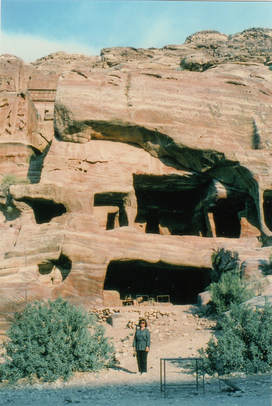

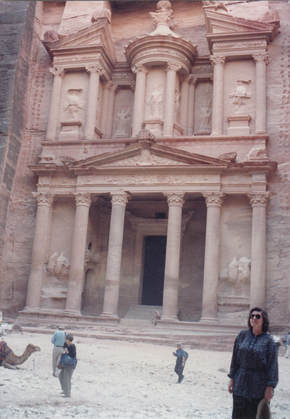

Sherrill, ancient Petra, Jordan

Sherrill, ancient Petra, Jordan The first of the temples, the so-called "Treasury," suddenly appeared before us as we emerged from the far end of the tunnel-like siq. More than a dozen stories tall, it was hard to imagine how anyone could have carved it out of the sandstone—and it was only the first of many such wonders, no less impressive because of the crouching camels and young Bedouins lounging in front of it. At last, Sherrill was following in the steps of her heroines, Gertrude Bell and Isabella Bird, two women of the 19th and early 20th centuries who defied the conventions of their times to explore the world, going alone to places that few European or British "ladies" went at all.

"Go ahead," Sherrill told me several times. "I'll stay down here in the shade."

"Why is it that the most interesting places have the worst roads?" I moaned.

Sherrill patted me on the knee: "This isn't nearly as scary as China."

"Not yet."

"How did it manage to survive for all these centuries?" I asked, as we hiked among the elegant theatres, Roman baths, temples, oval-shaped forum, colonnaded street, even a race course and an arch dedicated to Hadrian.

"Never mind," Sherrill replied, "just be glad it did."

Few tourists were walking the streets of Jerash when we were there in 1994, but it felt like a real city, a place where people could live, even today. We felt privileged that we were there and wondered why more people didn't come to experience this amazing place.

"No need to fear terrorists," one man told us. "This is a safe country."

Sherrill, Damascus, Syria, 1994

Sherrill, Damascus, Syria, 1994 We still saw few western tourists, but while we were in the country, U.S. President Bill Clinton also was there, meeting with the Syrian president for life, Hafez Assad, father of the current dictator. According to the newspapers, their meeting focused on the conflict between Israel and the Arab world. We saw no mention of the rights of Syrian citizens. We did see a number of large billboards in Damascus and other cities, though, of the smiling, shark-eyed Assad trying to look fatherly.

"It would be exciting to see Bill Clinton while we're here," Sherrill said, wistfully, but of course it didn't happen.

Sherrill in chador, Mosque, Damascus, 1994

Sherrill in chador, Mosque, Damascus, 1994 Every day turned into a treasure chest of experiences: archaeological sites, visits with people in their homes, trips to mosques, palaces, museums, a tomb reputed to hold the head of John the Baptist. It seemed to be a particularly good time to visit Syria because it was in transition, blending old and new customs, but we had no idea where this growing tsunami of change would sweep the people and the country.

If you find these posts interesting, why not explore the rest of my website, too? Just click on the buttons at the top of the page and discover where they take you—including to several complete short stories and excerpts from my novels. Please pass the posts on to anybody else you think might enjoy them.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed