Ready for More Adventures

Ready for More Adventures People love that question. When they asked which of the countries of the Middle East ("middle" from whose point of view?) and North Africa that Sherrill and I had visited did we like best, we usually said that they all were fascinating in different ways. Each one was an exciting opportunity for a curious traveler to open his or her heart to life-changing experiences. Well, it was true, back then. Still, Syria probably was our favorite.

"It's the people," Sherrill always said. And I agreed.

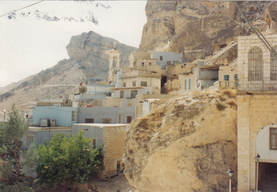

Ancient Village of Maaloula, Syria

Ancient Village of Maaloula, Syria Maaloula, a village tucked into the rocky mountain cliffs north of Damascus, was one of them, a place where the people still spoke Aramaic, the ancient language of the Bible, and where in an ancient church we found an altar that long ago was adapted from a pre-Christian one used for animal sacrifices, with a carved channel for draining blood. The morning after visiting Maaloula, Sherrill and I walked up the cobblestone street of a nearby town almost as old, passing a pair tiny old women in black leaning against the wind, the ochre stones of an ancient citadel behind them. Then, up some steps from the street, we came to a little church, tried the door, discovered it was locked.

Later that day, our friend Hala introduced us to the wonders of Krac des Chevaliers, the great crusader castle that dominated the rugged landscape from its hilltop. Hiking on its cobbled passageways, through its many levels, dark chambers, and cool stone rooms, we almost could imagine life in a medieval fortress/castle. From the battlements at the top to the base, where the stones were as much as 80 feet thick, the castle was more impressive than any Hollywood version. For a while, Sherrill played hide and seek with a couple of Syrian children until their mother took them away.

Sherrill with meze in restaurant

Sherrill with meze in restaurant A cramped little shop that sold antiques and small objects drew us in. Sherrill was intrigued by an antique brass pen holder with an attached inkwell that was etched with an ornate, interlocking leaf design. Curious, she lifted the little scallop-shaped cap to the inkwell and popped open the lid to the shaft made to hold pens and brushes. When we left the shop a few minutes later with the newspaper-wrapped treasure in her hand, we saw four tent-like figures like black ghosts facing the bright display window opposite. Even their gesturing hands were hidden by the inky fabric of the chadors. Behind the smudged glass, three bald mannequins flaunted skimpy brightly hued dresses that revealed most of their plastic bodies.

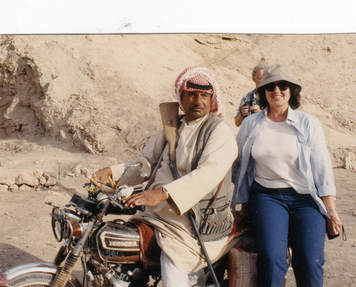

Sherrill and Guard, after the rain

Sherrill and Guard, after the rain "Thanks!" she said, ignoring my shake of the head and climbing onto the motorcycle behind the guard.

They bounced away, mud exploding behind them. When I finally reached the entrance, I found them drinking hot tea with our driver and a couple of our compatriots under a makeshift shelter. Before long, at least, the rain stopped, the sky cleared, and the ground began to dry. The guard even let me take a photograph of the two of them on the motorcycle.

Souk, Deir Ezzor, Syria

Souk, Deir Ezzor, Syria  Ancient Palmyra, Syria

Ancient Palmyra, Syria "It must be fun," said Sherrill. "And cheap."

The next day, we hiked through the three thousand year-old city, past marble temples and through the ornate remains of Zenobia's palace, where we lingered beside the mosaic-lined pools in which she'd soaked her royal body.

"Emperor Caracalla claimed Palmyra as a colony," our guide told us, "but its wealth gave it unusual freedom. Zenobia made Palmyra into an independent power—even dared mint coins with her profile."

"Maybe I'll find one," Sherrill said.

"You'd be arrested if you were caught trying to take it out of the country."

Desert tomb, Palmyra, Syria 1994

Desert tomb, Palmyra, Syria 1994 Later, after bouncing across the desert, we stopped at the limestone entrance of one of the underground tombs. Our friend had arranged something special for us. A pipe more than foot in diameter bridged sandy steps that descended to a pair of massive doors. Our guide ducked under the pipe with a flashlight and unlocked the stone doors, so perfectly balanced that they swung open easily.

Following him down the steps and under the pipe, we walked into the dry dusty chill of the past. With his flashlight and a single caged bulb shining through clouds of dust, we explored a tomb not denuded by grave robbers, with carved portrait slabs still protecting many stone shelves. Here, a curly-headed youth, there a proud middle-aged woman, hair elaborately arranged atop her long face. At the end of the room, a bas relief showed the entire family languidly eating Roman style. We followed the guide through the icy tomb to where a portrait slab had been lifted from one of the burial shelves. He aimed his flashlight inside, onto a skeleton, its shape twisted as if sleeping, a small clay oil lamp near the bony hand.

Temple of Bel, Palmyra, 1994, before ISIS blew it up in 2015

Temple of Bel, Palmyra, 1994, before ISIS blew it up in 2015 During recent years, the violence has persisted and escalated, destroying much of Damascus and Aleppo and their environs and other cities, as well. Many thousands of the country's citizens have died, been left homeless, and fled to other countries, but Sherrill and I treasured the welcoming smiles that greeted us across the country before this conflagration overtook them.

If you find these posts interesting, why not explore the rest of my website, too? Just click on the buttons at the top of the page and discover where they take you—including to several complete short stories and excerpts from my novels.

Please pass the posts on to anybody else you think might enjoy them.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed