"We paid money for this," Sherrill whispered, wiping sweat from my face.

Vientiane, we saw driving from the airport, was still a city free of high-rises and heavy traffic. Buildings from the French colonial era, most of them with wide eaves like sleepy eyebrows over weathered faces, broad verandahs, and shuttered windows, peaked out from among newer two and three story buildings. Circling around a massive Victory Arch built in the 1960s to celebrate independence from "foreign control," we drove to our hotel, where we passed out until the next day.

Sherrill, Morning Market, Vientiane

Sherrill, Morning Market, Vientiane  Sherrill, Motorbike taxis, Vientiane

Sherrill, Motorbike taxis, Vientiane "Look at the kids with those blades," I told Sherrill, as we passed boys cutting down clusters of bananas with machetes big enough to remove a leg.

"Don't fret. They've probably been doing it since they were babies."

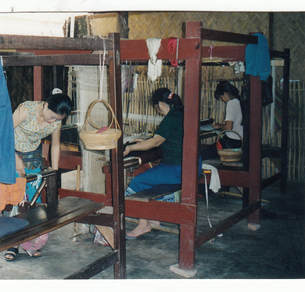

Weavers at Carol Cassidy's, Vientiane

Weavers at Carol Cassidy's, Vientiane  Sherrill, Buddhist temple, Laos

Sherrill, Buddhist temple, Laos "Oh! You're in room seventeen! Didn't anyone tell you not to use the tub?"

Monks with begging bowls, Luang Prabang

Monks with begging bowls, Luang Prabang At six the next morning, we walked out to where monks in their saffron-orange robes shuffled barefoot with their begging bowls past local people with bowls of sticky rice or other food. As each monk hesitated, each person dropped a wad of rice into the bowl, gaining "merit" toward the next phase of earthly existence.

"When a boy goes into a monastery," we were told, "it's one less mouth for his family to feed."

Booth with rocket bomb, rice whiskey village, Laos

Booth with rocket bomb, rice whiskey village, Laos During the Vietnam War, American planes flew over Laos to Vietnam, but had to return with empty bomb bays. If they still carried bombs in their guts when flying back, they dropped them onto Laos, which had the misfortune to be on the route to home base.

Villager hand-making paper

Villager hand-making paper  Hmong Village Woman

Hmong Village Woman "Happy birthday!" everyone sang.

"Where did that come from?" Sherrill asked.

Our friend Hala had ordered the cake by long-distance, even giving the recipe and decorating instructions.

"There were no cars in Vientiane," he said. "No modern amenities of any kind until recently, and the only medical treatment available was 'traditional.'"

Because of the relentless bombing of the country during the Vietnam War, he added, the need for humanitarian and medical aid still was enormous. Each year, he returned to Paris, but then came back to Laos to do what he could to help. The boat put-putted toward the center of the river, then as it slowly moved through the muddy water we talked and ate, the sun set, and lights started to glow on the two sides of the river, in Laos and Thailand.

To be continued....

Please pass the posts on to anybody else you think might enjoy them.

You also might enjoy reading the new bargain-priced e-book of my first novel, The Night Action. The book is available at Amazon and other online retailers. Click on the title or Here for the link.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed