Bruce & Sherrill on the Mekong, Cambodia

Bruce & Sherrill on the Mekong, Cambodia

"The city has a population now of about one million," she told us, "but under the Khymer Rouge it was empty. Everyone was sent to the country to work—unless they ran away or were murdered. Intellectuals, professionals, most educated people, were killed or driven out of the country and young, ignorant people from the country were recruited and brainwashed."

Phalla seemed determined to make sure that we understood the horror her country had endured. Despite the elegant Cambodian silk scarf around her shoulders, Sherrill told me later, Phalla reminded her of a nun teacher she'd had in grammar school.

"She always looked like she was badly disappointed with us. She liked swatting kids with her ruler—but never me."

From 1979 through 1989, the population of Cambodia dropped from seven million to four million. When Sherrill and I were there in 2000, it was about 11 million, half under fifteen.

Sherrill on the Corniche, Phnom Penh, Cambodia, 2000

Sherrill on the Corniche, Phnom Penh, Cambodia, 2000 "I was from a province near Siem Reap," Phalla said, balancing at the front of the bus as it careened over the uneven roads, "but my mother sent me to Phnom Phen because of war danger. Later, I returned and married, but when the Khymer Rouge took over the country, my husband and I were sent to a village far in the north. My son died because there were no medicines and two of my brothers were killed by the Khymer Rouge. Those were bad times."

"Look at that!" Sherrill pointed out the window.

In the center of a traffic roundabout we were circling, a giant revolver balanced on its hilt, barrel pointed skyward—twisted into a knot. It symbolized peace, but peace came too late for these people. All across Phnom Phen, we saw maimed and mutilated men and women and sometimes children, most of them war victims, often maimed by land mines. When we were on foot, they pursued us, displaying their wounds and stumps.

Later, we stopped at the park from which Phnom Phen Hill rises, a stupa and temple at the top, and climbed the stairway up, past giant statues of seven-headed nagas, sacred guardian snakes, to shrines not only to Buddha but also to Vishnu and other holy figures.

"People here," I said, "seem to be open to all possibilities."

"Or are hedging their bets," Sherrill countered. "And the way they drive around here, they need to!"

Sherrill at the Royal Palace, Phnom Penh, Cambodia

Sherrill at the Royal Palace, Phnom Penh, Cambodia During the Khymer Rouge period, we learned, the National Museum lost many important pieces, but we did see a few surviving sculptures that gave us an idea of Cambodia's artistic history. Later, we stopped at some workshops in which new Buddha statues were being made. Apparently, so many religious images were destroyed when Pol Pot ruled that now there was a boom in producing new ones—although most of the new statues we saw were crudely made. When they were finished, they were tarted up with scarlet lips and fingernails.

The cyclo drivers stopped to tug worn awnings over us, but they gave little protection from the wind-driven rain. We cycled along historic streets and new parts of the city, some people on bikes and scooters around us now holding umbrellas, but most were stoically becoming drenched. Finally, our little procession stopped in front of the Hotel de Royale, an old colonial place recently refurbished by the Raffles Group. Abandoning our cyclos, we squished up the driveway and into the luxurious hotel.

Dripping through the elegant lobby, we maneuvered around expensive wicker furniture, to a central courtyard. Hala told us that when she came to Phnom Penh nine years before she tried to stay at the hotel but it was so run down, with rats running through the halls, that she moved after one night. Now, it was the finest hotel in the city. The rain refused to stop, so we returned to our cyclos. Around us, traffic struggled in what turned out to be the last monsoon storm of the season. Peering from under my shredded awning, I saw a sad little elephant being led through the gray, slanting rain.

Village on Tonle Sap Lake, Cambodia

Village on Tonle Sap Lake, Cambodia Phem Lorm, our temporary guide there, a portly middle-aged fellow dressed in the loose brown shirt and pants of the Cambodian professional, spoke surprisingly formal English. As we bounced over massive potholes in the road, someone commented that it was like a battle zone. He turned to her with a fierce expression.

"Madam, this was a battle zone." Just as in Phnom Penh, he explained, the local population was sent out of Siem Reap—to the mountains. "Many of my relatives and friends died. Some were shot, others from diseases. But I survived, ladies and gentlemen. I was lucky. I didn't speak English for four years—afraid they would think I worked for the CIA."

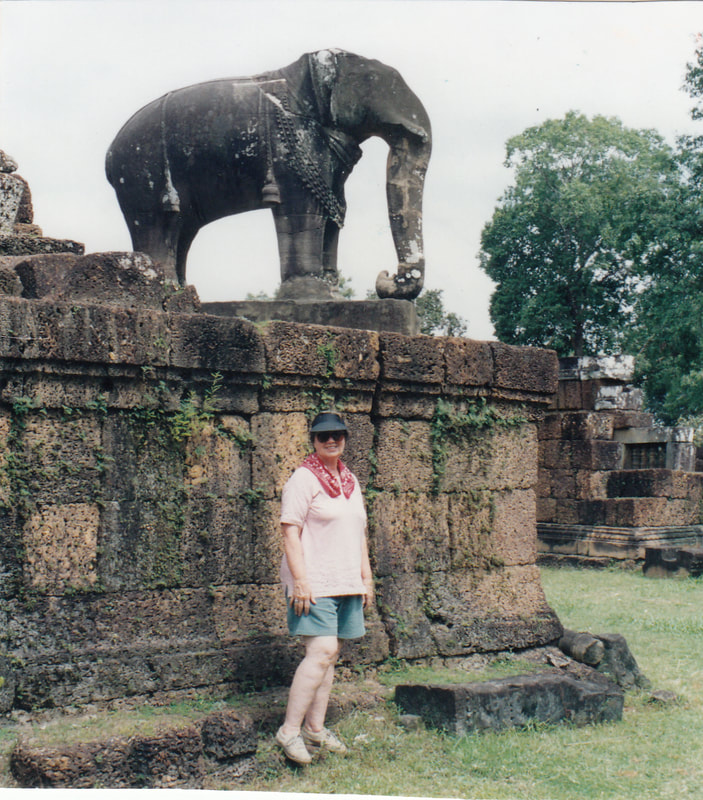

Sherrill at Rolous temple group, Angkor, Cambodia

Sherrill at Rolous temple group, Angkor, Cambodia "These villages look poor to you," Phem Lorm said, "but now people have food. Under Pol Pot, even animals died of starvation. At least, now, individual citizens can own land, animals, private property. It is okay to be educated. But much of the area still needs to be cleaned of land mines."

It was hard to believe that this countryside of sun-dappled fish ponds, palm trees, rice fields, and bamboo houses standing like storks on stilt-like legs had been the site of fierce fighting. We bumped and jolted to the Rolous group of temples. Climbing past guardian lions, we reached the first ninth century stone temple. Deeply cut bas reliefs caught the morning sun, creating bold patterns of light and dark. The foliage sprouting on the temple's tapering crown suggested fuzzy green hair.

Although recently the stone mountain of Angkor Wat was smothered by rain forest, now it was open to the sky again, with a huge moat representing the ocean. Kwon told us about the fighting here during the civil war. The Khymer Rouge soldiers were illiterate peasants who thought nothing of stealing sculptures from the temples to sell to the highest bidders.

"People died here," Kwon told us, "defending the temple."

Bullet holes, we saw, as we hiked across the causeway to the temple, still pockmarked the paving stones. The bullets hit at an angle, leaving troughs in the sandstone, as if mineral-eating worms had infested the causeway. We gazed up at the towers, impressed by their strange beauty and what they'd endured over the years.

"Our empire," Kwon told us, his features taut with pride, "stretched from China to central Vietnam and the South China Sea."

"They look like Kwon," Sherrill whispered to me.

She was right: the same broad cheekbones, wide mouth, and high forehead above shadowed eyes—the same proud dignity.

As we hiked across the dark dirt, we saw that all of them were missing body parts. Feet, hands, legs had been replaced by stumps and scars. Looking up at us hopefully, they played their makeshift instruments with increased vigor. What could we do, but tuck tattered riels and dollar bills into their belts and pockets and drop coins into the tin cans waiting on the hard earth?

Landmine warning, Siem Reap, Cambodia, 2000

Landmine warning, Siem Reap, Cambodia, 2000 To be continued....

Please pass the posts on to anybody else you think might enjoy them.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed