Sherrill & Bruce, Rangoon, Burma

Sherrill & Bruce, Rangoon, Burma

It was like, Sherrill said, Dorothy opening the door of her gray Kansas house to find herself in a very hot Technicolor Oz. Some of us, when we adjusted to the glare and heat, joined the line of the faithful buying tiny pieces of gold leaf to have affixed to the stupa's spire.

"I can't decide which channel is the most boring," I told Sherrill.

"Definitely the speeches," she said. "At least, we can't understand them."

We arrived so late that we couldn't see much as we drove into Rangoon—or Yangon, as it was officially called, just as the generals preferred the name Myanmar to Burma. The country had been closed to the rest of the world for more than thirty years. "David," the guide who met us at the airport acknowledged this, but added that slowly it was starting to open up—and we were among the first to be welcomed under this new policy. Soft-spoken and gentle, he wore the traditional Burmese outfit: a short jacket and an ankle-length sarong known as the longhi tied at his narrow waist, with sandals. Often, he seemed to have a wistful tone when he spoke.

"The Burmese are not good at living systematically," David explained. And, of course, the British were great organizers. Apparently, the Burmese generals ruling the country were pretty good at controlling the population, as well.

We were there during the 2000 election in the United States. The weather in Burma that autumn was okay for traveling, but the political climate we'd left behind at home was uncertain. We had mailed our absentee ballots before leaving, but were kept in suspense about what was happening in the U.S. because of Burma's communication blackout.

"The goal of Buddhism is freedom from attachments," David explained.

Weaving cloth for Buddha

Weaving cloth for Buddha Also, people worked to collect "merit" so they could enjoy a better next life. They believed in reincarnation and karma—what you do returns to you. In one temple, just below a massive Buddha, several women were weaving gold cloth to drape on the statue. They were earning "merit," but also competing for a prize to be awarded to the woman who wove the most cloth.

"What's the significance of that?" Sherrill asked, indicating the pale tan designs and marks on the faces of many women and children.

"Sandalwood paste," David explained. "For beauty and sun protection."

And what about the black and red smiles on many people's faces?

That was from the betel nuts that they liked to chew because it gave them a mild "high." It also explained the red puddles we saw spattered across the pavement.

Down on the waterfront, lean, sinewy men in longhis were bent almost double as they unloaded heavy rice bags from boats and carried them up steep ramps to waiting trucks. Back and forth they marched, in a machine-like parade. Behind them, British-era ferry boats crossed the river, sometimes continuing to other delta ports. Hiking along the narrow streets, dodging pedestrians and carts, past weathered colonial buildings and open markets, we passed unfamiliar vegetables and fruits, hunks of raw meat, and fish of unusual shapes and colors, patient, fatalistic vendors behind the stands.

Heading off on my own to look for bookstalls, I took a cab to a different part of town, riding with a middle-aged cabbie who spoke English. He wanted to talk about the presidential election in the United States. The generals may have imposed a news blackout in Burma, but the people knew about Al Gore and George Bush and had opinions. However, when I mentioned the 1990 election held in Burma, when Aung San Suu Kyi, daughter of General Aung San, assassinated founder of the democratic state, won, but wasn't allowed to take office, the cabbie became silent, then started pointing out places of interest that we were passing.

Glass blowing workshop

Glass blowing workshop "This country needs more lawyers," Sherrill commented. "Or, at least, OSHA."

We both knew, however, the generals weren't likely to start up an Occupational Safety and Health Administration and the Burmese, taught to endure what life handed them, weren't likely to demand it.

When we arrived at the Heho airport, a trio of military VIPs seated at the front of the plane began to follow a tall bodyguard in a longhi to the door at the rear when the stout peasant woman blocked their way with her shopping bags and large plaid-covered backside. With surprising patience, the VIPs gestured to their bodyguard not to worry and waited while the woman pulled herself together.

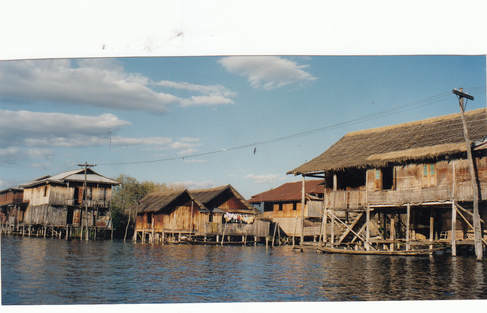

Sherrill, Golden Island Cottages

Sherrill, Golden Island Cottages "Buy me that, daddy," Sherrill teased, pointing to a copper-colored betel nut cutter on one of the tables. She seemed almost surprised, when I did.

On a large stucco gate to a side road we saw a sign in both Burmese and English announcing a combination golf course, resort, and amusement park.

"Who will go to that?" I asked.

"Chinese Shan," the local guide told us, "rich from the opium trade."

We were in the Golden Triangle that grew opium poppies for the Thais and Chinese. Ultimately, heroin was made from the opium and shipped to other countries, including the United States, so we weren't too surprised when we saw armed soldiers and warning signs in both Burmese and English.

"And they let us get this close?" asked Sherrill.

I shrugged. "Just don't try any funny business."

To be continued....

Please pass the posts on to anybody else you think might enjoy them.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed