Sherrill gazing up at an oversized Buddha wedged into a pagoda, representing an imprisoned Burmese king.

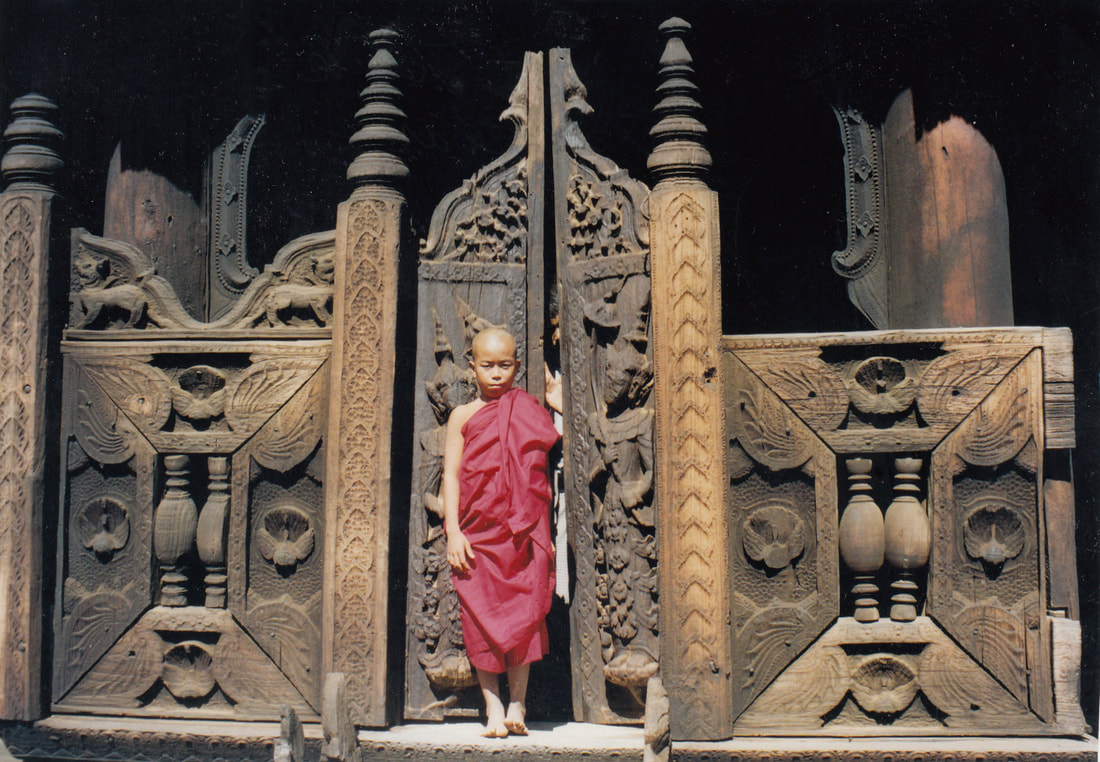

A child monk with shaved head and innocent eyes at the door of a teak monastery.

A 1950 bus built from teak in a jungle village.

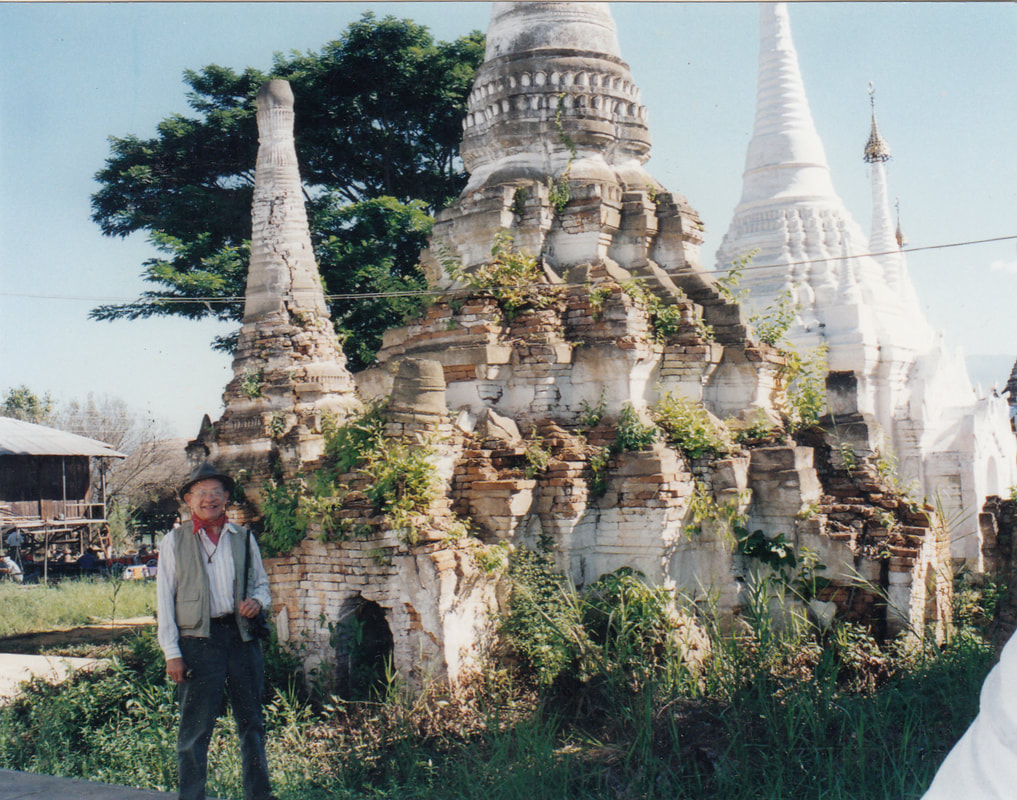

A forest of ancient Buddhist stupas.

Old teak bus, Burma

Old teak bus, Burma Sherrill shook her head. "Some poor employee is probably in a back room rerolling toilet paper to make these mini-rolls,"

The next afternoon, before the evening balloon rising, Sherrill and I walked down the hill from our hotel, past guest houses and old homes that had been around since the days when the colonial British came to escape summer heat, to the main street, now lined on both sides of the pavement with temporary booths. Most of them were selling food and drink, but some were hawking posters and photos of Burmese musical stars, souvenirs of the festival, and toys—especially plastic guns, some of them very realistic.

Then, in our warmest clothes, flashlights in hand, we followed our friend Hala downhill to the festival as music throbbed through the trees, joining local people going the same direction, including groups of monks, some as young seven or six years old.

"Look!" Sherrill told me, gesturing to a very small Buddhist monk with shaved head and red robe, eyes wide with excitement, his hands clutching a teddy bear purse.

From our vantage point on a small rise, we watched the undulating sea of human silhouettes, the candles of vendors flickering among them.

As that balloon continued its ascent, another group began readying their balloon and a third brought in theirs on a decorated truck and trailer, led by men and boys playing drums, chanting, and dancing. Seventeen balloons went up that night and more than 400 ascended during the week-long festival.

We could enter the temples, now, only through arcades selling religious souvenirs and offerings for Buddha. Shoes weren't allowed in the arcades, any more than in the temples, which forced us to maneuver our naked feet among bird droppings and red globs of betel nut juice spit.

After a barefoot hike through the arcade at the Maha Muni Temple, we came to a crowd of men shuffling toward a platform where we could see only the top half of a serenely smiling bronze Buddha. As we got closer, we discovered that his lower half had been transformed into a lumpy gold mass—the result of countless small offerings of thin gold leaf pressed onto him. Women weren't allowed into the shrine surrounding the statue because they would've had to pass in front of praying monks, which would have been—we were told—disrespectful.

"That," Sherrill declared, "is ridiculous. And sexist."

The other women in our group agreed, but they all had to wait below.

The next day, I still didn't feel well enough to go on the scheduled expedition, so I wrote, drank water, took my temperature, wrapped myself up, and sweat. And sweat. Later, as long as I was hanging out in the hotel, I went down to reception and asked if I could send an email. The clerk told me that I could use word processing to write my email onto a disk. They would send it for me. Well, I decided, it was better than nothing. I had no doubt that it would be scrutinized before it was sent, but my daughter back in California did get the email and it even seemed to be what I'd written.

Sherrill en route to ancient capital

Sherrill en route to ancient capital  Shwezigon Pagoda, Pagan, Burma

Shwezigon Pagoda, Pagan, Burma Some of the temples were decorated inside with delicately drawn frescos, some rose to astonishing heights, manmade mountains of ornate stone, many were covered with otherworldly shapes. One temple built in 1218 rose in two levels to a hundred and fifty feet. A twelfth century temple rose in wedding cake tiers to 200 feet. Several of us climbed the huge Mingalazedi Temple to watch the changing hues of the sky wash over the temples and pagodas as the sun set. Climbing down the precipitous, uneven steps in the dark was less fun.

Sherrill and temple, Pagan, Burma

Sherrill and temple, Pagan, Burma

Back home, reading a history of the Pagan area, I discovered that it nearly became the site of a major World War II battle between retreating Japanese forces and the allies. Fortunately, one man, G.H. Luce, a scholar who had devoted his life to studying Burmese history and culture, went to the allied headquarters to stop the pursuit through the archaeological zone. For this, whether people know his name or not, G.H. Luce will always be one of the heroes of world civilization.

"People are afraid of informers," he told me. "Only when we were trekking in the wilderness would they open up to me."

When they did talk freely, he said, they expressed anger about corruption in the government. Despite profits from agriculture, oil production, ruby mining, lumber harvesting, and other resources, the people grew poorer. The money all was channeled, he told me, to the military dictators. The people were angry, but afraid. He'd been surprised to see that the young Burmese were sincere and devout Buddhists, but felt that the religion made them too docile.

To be continued....

Please pass the posts on to anybody else you think might enjoy them.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed