"Thank you for your courage flying so soon after the events of September 11," he said. "New procedures are now required on the plane. No wandering or milling about. You'll have to stay in your seats and ask the flight attendants to go to the lavatory."

After we'd boarded, our captain repeated what the first had said, adding: "For the first twenty minutes of the flight no one can get up, not even to go to the lavatory."

Later in the flight, I noticed that before one of the pilots came out of the cockpit, a flight attendant blocked the aisle with a food cart until the pilot was locked again behind the cockpit door. When we flew into Kennedy, where we changed planes for Paris, we saw the Manhattan skyline minus the twin towers. The Empire State Building again dominated the view.

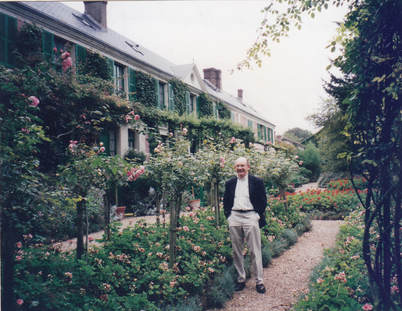

Bruce at Monet's house & garden, Giverny, France

Bruce at Monet's house & garden, Giverny, France "They look just like the paintings," Sherrill said, as I followed her among Monet's gardens and ponds.

As a gardener, Sherrill loved exploring the paths and alcoves of the gardens, studying the range of colors, the textures and patterns, the way the light drifted across the flowers, trees, and water. Years before, in Japan and after, we'd learned a little about Japanese prints and admired those that Monet had collected, hung in his house, loved, and been inspired by. After a glorious half day in Monet's flowery wonderland, however, we discovered that there was no bus back to Vernon.

"Okay," I said, "I guess we'll walk."

"Don't worry." She patted my back. "It'll be fine."

So we did, three miles back to the Hotel d'Evreux, in a restored medieval building, where we cleaned up under the sloping ceiling of our room before descending to the cave-like dining room and a Michelin two-star dinner that we savored despite the glassy-eyed stares of an antlered deer and a bristly boar on the wall above our table.

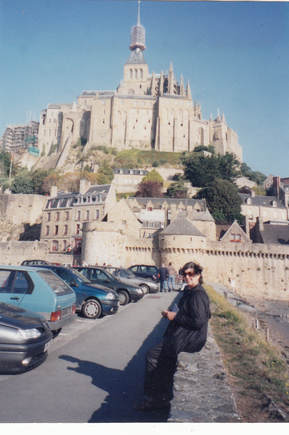

Sherrill on Mont St. Michel Causeway

Sherrill on Mont St. Michel Causeway "You wouldn't have a room for us, would you?" I asked the receptionist at a small hotel wedged into a sharp bend on the steep main street.

"Of course, monsieur," she smiled. "A nice one with a view toward the bay."

"Virtue rewarded," Sherrill whispered in my ear.

That evening, after exploring the island and abbey, we relaxed with drinks in a cocktail lounge looking over the bay, while young French people played bagpipes and danced on the dry mudflats below. Later, after dinner, we walked out onto the causeway to look back at the island and abbey. With the day trippers gone, it was easy to imagine this still was the medieval town. Before we left a day later, the hotel receptionist called ahead to Tours, our gateway to the Loire valley, to reserve a room for us.

"Come stay with us again, madam," she told Sherrill. "We enjoyed having you."

"Anybody with a ruler can do that," she muttered, "but it's not what I call a garden."

Bruce at Tintin Museum, Cheverny

Bruce at Tintin Museum, Cheverny The other palaces of the Loire had their charms, but two especially stand out in memory. The chateau of Chambord was ridiculously huge, but we were amused by the twisting double staircase designed by Leonardo so that Francis I's queen and mistress could pass without confronting each other. The palace of Cheveny was the model for the chateau shown in the Tintin illustrated adventure stories that our son-in-law and grandson had enjoyed. In fact, a museum on the grounds was devoted to the character of Tintin, his comrades, and their adventures—too bad that Paul and Leo weren't with us.

It was becoming clear that the world was never going to be the same—and probably in ways that we couldn't imagine, yet.

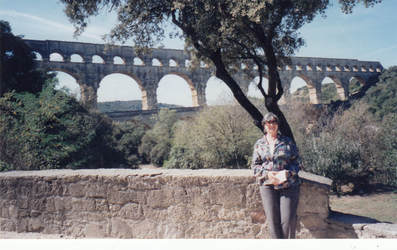

Sherrill, Pont du Gard, Nimes, France

Sherrill, Pont du Gard, Nimes, France Suddenly, there it was, the huge aqueduct, stretching across a steep gorge above a river bed, as impressive as ever after two millennia. We walked across it, gazing back from different vantage points. People were sunbathing on the gravel beach below, swimming in the river, and hiking around it, as if it were a natural phenomenon, something they might find in Yosemite or Yellowstone.

"Remember that black olive pie?" Sherrill or I would ask the other years later, and we'd nod and smile and reminisce.

For a while, we were afraid that we'd have to sleep in a doorway of the monumental Pope's Palace in Avignon, but finally we found a modest room and spent the rest of the day being awed by the magnificence of the Pope's court and wandering the twisting medieval streets until we reached the river and the "Pont d'Avignon," where Sherrill sang the old song to me. Everything, we congratulated each other, worked out for us. Then it was on to Milan, by way of a couple of days in Nice, staying in a seedy little hotel run by a talkative old lady with hennaed hair and scarlet toenails, right out of a Tennessee Williams play—French version.

Lee & Sherrill outside Venice apartment

Lee & Sherrill outside Venice apartment The train hurtled across the top of Italy, through Brescia, Verona, Vicenza, and Padova—all places we'd return to on later trips—reaching Venice in the late afternoon. By the time we bought our week passes for the vaporetto and made the trip on the #1 the full winding length of the Grand Canal to the Arsenale stop, it was five o'clock. We discovered our friends sitting under an awning at a cafe facing the waterfront, eating gelato and sipping coffee. It was hard to believe that it had been several years since we'd seen each other. We joined them for coffee until the "Capitano," the colorful fellow who was renting us the apartment, arrived to turn over the keys—which he finally did with a flourish and many explanations, pronouncements, and good wishes.

Karen, Bruce, Sherrill at Arsenale, Venice

Karen, Bruce, Sherrill at Arsenale, Venice  Sherrill, Trieste Marina

Sherrill, Trieste Marina "They beat us here!" Sherrill gestured at the fancy boat. "They could've given us a ride."

Visitors to Trieste can get a James Joyce walking tour map now and will pass a statue of Joyce as they walk up from the train station and harbor, but none of that existed then. Still, we knew that Joyce and his Nora left that same station when they arrived in 1904 and he parked her on a bench across the street while he found a place to stay—and got drunk. As we walked those streets, passing the marina and turning toward the hills, we couldn't help but think of Joyce—after all, he lived there 15 years. At the top, we looked out at the red tile roofs in front of the blue-green Adriatic, visited the remains of a Roman forum, and then strolled down to the old town for the two-hour train journey back to Venice.

Over the years, Italy had become our favorite destination: we knew that we'd never discover all of its treasures, but it was fun to try. From Ravenna, we rode the train to Verona, another city in which the ancient world and succeeding centuries were jumbled together. The bathroom in our hotel room was so small that we had to put our feet in the shower to use the toilet, but nearby stood the Romanesque Basilica of San Zeno, Sherrill's second favorite church in Europe (after Vezalay in France).

The trains in Italy were frequent and usually on time. From Verona we sped up to Lake Como, where we bought a ferryboat pass so we could explore the towns around the lake. Then it was back to Milan. Early one morning, we waited outside Milan's Tourist Information Office until it opened so we could buy timed tickets for the day's three-hour city tour that included a guaranteed visit to Leonardo's restored "Last Supper" mural, now protected by a modern security system and bullet-proof glass. We'd seen it 20 years before, but not since this restoration. The colors and lines of the painting were truer, now, making it easier to feel the human drama of the scene.

A few more days in Milan, where we ran into our friends Lee and Karen again, and it was back to California, but this wouldn't be our last trip to France and Italy.

To be continued....

If you find these posts interesting, why not explore the rest of my website, too? Just click on the buttons at the top of the page and discover where they take you—including a bio, information about my four novels, along with excerpts from them, and several complete short stories.

Please pass the posts on to anybody else you think might enjoy them.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed