This was saying something, since by this time she'd seen a good chunk of the world. I couldn't contradict her, though, because we had run into some outrageously sexist behavior there. However, despite that and because of the efforts of our good friend Hala, Morocco turned out to be one the most exciting and memorable of our travels.

By day eight of the trip, our little group was on its third national guide. The first two had resented working for a woman and had assumed that their job was to take us to pricy shops where they'd get kickbacks. Marwan, our third guide, was different. His English was a little shaky, but for the rest of the trip, in his full-length djellaba and pointed yellow babouches (slippers), he helped us through cities and over mountain paths, actually happy to show us his country.

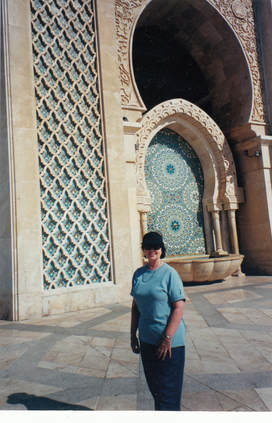

Sherrill at Hassan Mosque, Casablanca

Sherrill at Hassan Mosque, Casablanca "Why isn't there space down here for women?" Sherrill asked her.

"Oh," replied the guide, "women are free to worship the same as men—up there."

Later, we learned that the 38 year-old new king, Mohammed VI, had recently married a commoner who was a computer engineer. And, we were told, the new parliament about to open had thirty-five women members. The crowds of young people and swarms of children that we saw verified that 71 percent of the Moroccan population was under 25 years old. Maybe there was hope for the future.

Medina gate, Fes, Morocco

Medina gate, Fes, Morocco A drive through more olive groves on another day took us to Volubilis, the Roman empire's most remote outpost. From here, lions and Barbary bears were sent to Rome to battle gladiators and wheat and olive oil were shipped to feed the restless masses. Less than half of the site had been excavated, but what we saw was impressive—especially the huge, richly detailed mosaics. Bulky stork nests balanced precariously atop some of the limestone columns, waiting for their tenants to return from the north.

Medina, Fes, Morocco

Medina, Fes, Morocco  Weavers, Fes souk, Morocco

Weavers, Fes souk, Morocco Outside the medina, we could see a dozen minarets of different sizes and shapes rising out of a sea of brown buildings. Five times a day, we heard the competing calls to prayer. One afternoon, I walked through the nearest gate into the medina. Young men and boys rushed up to guide me. I refused them, but they followed me down the steep, narrow streets, haranguing me in broken English. I could see that I'd get lost among the abrupt turns and dividing and re-dividing lanes, so I found my own way out.

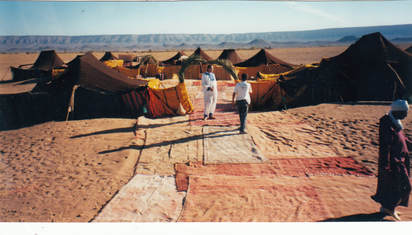

Bedouin camp with wild cat "rocking horse," Morocco

Bedouin camp with wild cat "rocking horse," Morocco Continuing past volcanic cinder cones, we entered a rugged country of bizarre rock formations, mines, and fossils. After a while, we stopped in a small Berber settlement for lunch. While the rest of the group was having tea, I crossed the road to a shed in which a Berber man had set up a rock shop that included geodes, nautiloid fossils, trilobites, and other fossils. I bought a perfect trilobite bigger than my fist, still within its rocky covering. Later, Don, a geologist in our group, assured me that it was the real thing.

Sherrill on High Atlas Range road, Morocco

Sherrill on High Atlas Range road, Morocco We had traveled 450 km over the mountains in one day, partly along the winding Ziz river gorge, the result of centuries of erosion, then following ancient caravan routes into the desert. Often the road was bordered by coppery red strata that had been upended and twisted by ancient cataclysms. When we passed through small towns we noticed that people in the south dressed more conservatively than in the north, the women in black chadors with face veils—although they seemed to be doing most of the work while the men lounged in cafes, drinking coffee or mint tea.

Sherrill, lunch stop, Todra Gorge, Morocco

Sherrill, lunch stop, Todra Gorge, Morocco A party of Germans, we discovered, had ridden out on camels even earlier and already were silhouetted on the highest dune against the sky as it slowly turned pink. The blue robes of their camel drivers stood out sharply against the rosy color of the dunes.

Valley of the Kasbahs, Morocco

Valley of the Kasbahs, Morocco The next morning, we set out across hard-packed desert, continuing deep into a gorge where red and orange desert cliffs soared to 2,000 feet, only a narrow strip of blue sky between them. That night, we stayed at a mud brick hotel modeled after the kasbahs of old, then in the morning drove into another canyon of high cliffs, following the road of "A Thousand Kasbahs," until we reached the hilly city of Ouarzazate and its ancient kasbah that was being restored with help from UNESCO.

Sherrill at Jbel Zagora Oasis, Morocco

Sherrill at Jbel Zagora Oasis, Morocco A classic car club from France touring Morocco had reached Ouarzazate just before we arrived, their cars corralled in the hotel parking lot, ranging from a fifties Impala to a couple of antique Citroens to old MGs, Mercedes, Jaguars, and BMWs. Most of the drivers were in the hotel when we arrived, but a few still wandered among the cars, dusting them and stroking their shiny skins as if they were race horses cooling down after a run.

A day later, we began the trip south on the old caravan route across the rugged Anti-Atlas range, passing villages populated by Berbers and desert Arabs. When we reached Zagora, the last oasis before the Sahara, we saw the town long before we entered, standing on the edge of the desert like a mirage. Although there had been an oasis there for centuries, much of it had been rebuilt. In the late afternoon, we drove a short distance to the base of the Jebel Zagora mountain, where trekkers were getting Land Rovers ready for desert exploration. We, however, were going to climb the mountain so we could watch the sun set from its summit. Four of the women, including Sherrill, elected to ride camels, rather than climb.

Marwan led the rest of us up a trail, zigzagging among rocky outcroppings. Several times, as the sun sank lower in the sky, we stopped to catch our breath and look at the view. By the time we reached the summit, we looked out at an impressionist painting of red, maroon, dark green, black, and brown running together. Marwan called on his cell phone to order a couple of Land Rovers to take us back down. However, when I saw how narrow, twisty, and steep the rocky road was—and how far the drop over the edge was—I decided to walk down. One other person said she'd walk down with me, rather than wait for the Land Rovers.

Desert camp on the edge of the Sahara

Desert camp on the edge of the Sahara A multihued wall of tent material hung from poles, beyond it a circle of tents illuminated by strings of small electric lights. Beyond the camp, we saw only blackness. As we stepped through an opening in the fabric wall into the first of two large circles, Bedouin men greeted us and took us to the tents where we'd spend the night. Around midnight, we were told, the electric lights would be turned off to save the generators, but lanterns would be set out.

We cleaned up as well as we could, then sat at two round tables where a feast of Moroccan dishes appeared. After all that exercise, we were starving. It had been quite a day and evening. When we woke up in the morning, we saw that we were surrounded by rolling waves of sand. A gold and brown scorpion crawled onto the red carpet, barbed tail aloft.

"It won't bother you," Sherrill told me, "if you don't bother it."

Just the same, I wasn't happy until I'd crushed it and got rid of the remains.

After breakfast, we drove back along the route we'd come, returning to Ouarzazate, past rugged rock formations and several kasbahs, some crumbling, others still standing on the cliffs.

Medina street, Marrakesh

Medina street, Marrakesh Returning to the other side of the river, we found a little outdoor restaurant with a view of the kasbah. The food was good, but the place was swarming with flies. We had to spread paper napkins to protect our plates.

"One of reasons that Jimmy Carter was given the Nobel Peace Prize," Sherrill told us, "was his work to eliminate the flies in Africa that get in people's eyes and cause blindness."

"Thank you for sharing that," replied one of the group, waving flies away from his face.

"Does North Africa count?" asked somebody else.

Then we began our climb into the High Atlas mountains, through a lunar landscape of red, orange, and brown cliffs and canyons. It was hard to imagine camel caravans making their way along that route, but they did for hundreds of years. Finally, we descended into the valley and reached thousand year-old, pink-hued Marrakesh, for centuries an important caravan stop, then a French city, now a major arts center and the base for our final week in Morocco.

One morning, we explored the notorious Marjorelle Gardens, owned then by Yves Saint-Laurent, but created between 1922 and 1962 by French painter Jacques Marjorelle. Sherrill was amused by the stylized garden, the palm trees, cactus beds, fountains, and ponds. Vivid blue pavilions, urns, low border walls, and a blue and rose-brown house helped set off the plants. Morocco seemed to be a land of dramatic contradictions, of economically desperate people doing whatever they needed to survive and ferociously stylish decadence.

Sherrill, Marjorelle Gardens, Marrakesh

Sherrill, Marjorelle Gardens, Marrakesh A side trip through harsh but oddly beautiful country took us to the coastal town of Essaouira, where Orson Welles filmed part of his low-budget Othello in 1948, shooting part of it in a steam bath with his cast draped in sheets because he couldn't afford costumes. Small blue boats rested on the stone embankment below an 18th century Portuguese fort. Several of us of walked out to a small seafood restaurant. Sherrill ordered sardines and was astonished when she got a platter so large that we shared it with three other people.

To be continued....

Please pass the posts on to anybody else you think might enjoy them.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed