Sherrill about to explore the Dalmatian Coast

Sherrill about to explore the Dalmatian Coast The summer of 2007 broke records for heat and wild fires along the Adriatic Sea from Slovenia in the north to southern Greece. That also was the year that Sherrill and I set out with our friend Tom to explore the five countries along that coast. The temperature didn't start out unusually hot, but it steadily, relentlessly, rose. When our little Slovenian plane from Frankfurt to Ljubljana dropped through the clouds enough to give us a view of Lake Bled circled by forested mountains, it didn't occur to us that an historic heat wave was starting down there.

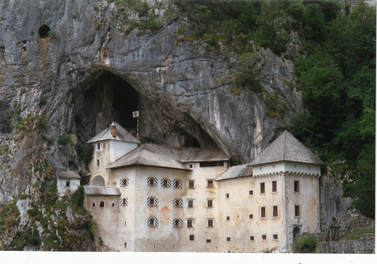

Predjamski Grad Castle, Slovenia

Predjamski Grad Castle, Slovenia Our young guide, from neighboring Croatia, took our little group to dinner in a small town hidden in one of the forests, the front walls of many of its seventeenth and eighteenth century buildings decorated with frescoes. A drive into the mountains one day brought us close to the Italian and Austrian borders, where we visited the largest cave complex in Europe. A tram took us through a long tunnel and several large chambers until we reached a cathedral-sized space where we continued on foot. During World War II, the Russians forced prisoners to build new walkways and bridges to expand access to additional chambers.

After the serenity of Lake Bled, we expected the capital city of Ljubljana to be jarring, but we enjoyed walking along the city's narrow streets, past parks and handsome old buildings. Several streets were pedestrian only and many were lined with open-air cafes and markets. With a population of only 200,000, it hardly felt like a major city.

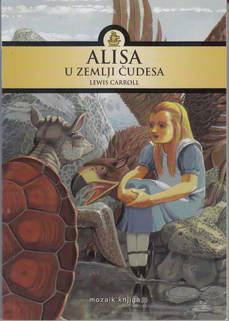

Croatian edition of "Alice in Wonderland"

Croatian edition of "Alice in Wonderland" The next day, we saw people lighting candles and praying at shrines inside the shadowy gate to the upper town, remembering victims of the Croatian war for independence. From 1991 to 1995, the Serbs often attacked the city, but never occupied more than its outskirts. One woman we met said that as a child during one siege period she spent six months in a basement.

Sherrill on the ship "Athena"

Sherrill on the ship "Athena" "It always happens," Sherrill whispered, "every trip—weddings."

"It must be symbolic."

She smiled. "If you want symbolic, look over there."

Down the path, we saw two young men in dark suits with clip-on ties and little badges on their breast pockets—a pair of Mormon missionaries. We seemed to run into them almost as often as wedding parties.

Sherrill, Plitvice Lakes, Croatia

Sherrill, Plitvice Lakes, Croatia "Croatia is shaped like a crescent, Bosnia-Herzegovina pushing at its center. The border here once was the line of defense against the Ottoman Turks."

"More symbolism," I whispered to Sherrill.

We continued south, passing through more ruined towns and villages, toward the ancient city of Split, where the Athena, our 50-passenger ship waited. Our guide gave us a short history of the area—leading up to the birth and then the death of Yugoslavia, a bloody tale of ethnic conflict from the seventh century into the twenty-first. Landmines still lurked around there, she told us.

"For your own safety, I can't stop the bus, not even for photos."

"Just like in Cambodia," I whispered to Sherrill.

Entrance to Diocletian's palace, Split, Croatia

Entrance to Diocletian's palace, Split, Croatia The legend was that Diocletian's palace was so huge that eventually an entire city fit within it. Soon, we saw that this was not just a legend. With a footprint of more than 260,000 square feet, it easily had held the shifting populations of ancient, medieval, and renaissance towns. Even now, at least 3,000 people of the modern city lived inside the palace, many behind walls constructed 1,200 years ago. In the center, we found what once was the palace's great hall, now an open-air square. Nearby, we heard singing: five men in black, we discovered, their voices rising powerfully in a gigantic domed room. One of the sixteen granite sphinxes that Diocletian brought from Egypt pointed the way to the main "street" just beyond. Only three of the sphinxes survived; the others were smashed by early Christians.

Hopscotching from one era to another during the next days, we drove across a small bridge to the medieval island town of Trogir and hiked along its narrow streets to a little square, complete with a miniature Romanesque church, where we found in a small chapel a bearded figure hanging upside down from a hole in the ceiling.

"What is that supposed to be?" I wondered aloud.

"It's God," Sherrill said, pointing. "Look."

The clue was that he was holding the world in his hand.

Sherrill on the "Athena," sailing the Adriatic Sea

Sherrill on the "Athena," sailing the Adriatic Sea "What is that?" he asked, pointing to the streamlined plastic shell of the orange tender bobbing in the water. "A submarine, or what?"

Hvar, long ago a haven for pirates and now known more as a summer resort than for its thirteenth century walls, was pretty, but the next, larger, island that we reached two days later appealed to us more: Korcula, birth place of both Marco Polo and our guide.

"That's where I went to kindergarten." She pointed to a limestone building shimmering in the sunlight above a great stone wall. "My father was a sea captain—so was the father of a boy in my class. We'd stand at that big window and look out to sea for our fathers."

As we began hiking past the city walls and towers, the day already was getting hot.

"That's the way it is, now," she told us, "extreme. Very hot or very cold."

I noticed a sign that someone had painted on the seawall and asked her to translate.

"Look at us," she read, "we're still here."

The street pattern was designed to prevent winter winds from howling through the city. However, that also meant that we didn't get any breezes to help with the heat. We went into the Romanesque cathedral primarily to cool off, but were rewarded with a recently restored Tintoretto painting of St. Mark flanked by St. Bartholomew and St. Jerome, its rich colors of burgundy, gold, black, and white freed from centuries of dirt and varnish.

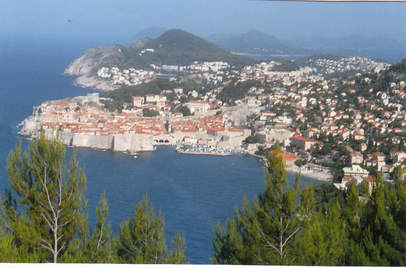

Dubrovnik, Croatia from cliff road

Dubrovnik, Croatia from cliff road Why? What compelled them to do it? That was our question when, early the next day, we drove along the road winding above this unique city and looked down from where the Serbs had shelled it. And why, although Dubrovnik had been designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site, did no one from the West try to stop the attack? With mixed feelings, we walked across the historic bridge and through the old gate into the city. The streets were narrow enough to shade us from the heat of the day—except when I went up to walk on the old walls while Sherrill wandered among the crowds on the streets and shops below. From above, the rich colors—scorching blue sky, dark sea, orange and red tile roofs, and gray stone walls—might have been painted by an old master.

War damage, Dubrovnik, Croatia

War damage, Dubrovnik, Croatia One evening, our guide took several of us to visit and have dinner with some local people at their farm close to the Montenegro border. "During the war," she told us, "the Montenegrins invaded and occupied this area. They burned many of the farms, including the one we're visiting." Until the Serbs under Milosevic stirred up ancient hatreds, the people on both sides of the border had got along together.

Luko and Mira, a middle-aged couple married thirty years, welcomed us at a stone farmhouse with an orange tile roof, blue wisteria draped over the entrance. Opposite, behind a fence, a lazy-eyed donkey and some sheep grazed.

I asked, with our guide's help as translator, if they were surprised when the Montenegrins invaded. Of course, they said, they had never imagined that such a thing could happen. They showed us snapshots taken by neighbors of their burned and gutted farmhouse. Luko had stayed to fight, but Mina and the children went to Dubrovnik where they lived in a hotel for eight years—even though the city was under siege.

Looking down on Kotor, Montenegro from the defensive mountain walls

Looking down on Kotor, Montenegro from the defensive mountain walls We'd waited until 5 PM to start, but the heat still was fierce. We gulped from our water bottles and mopped our faces with handkerchiefs, sleeves, whatever we had, stopping now and then to gaze over the tile-roofed town to the bay and along the gray rocky face of the mountains, continually changing shape as the light moved. Finally, more than an hour later, drenched with sweat, we congratulated each other on reaching the top. Then, after a brief rest, the seven of us began to trudge down over the slippery broken stones and loose gravel. The first to reach the harbor stripped to his underwear and jumped into the water.

"What were you four Croatians doing when the war started in 1991?"

Our guide explained that she'd left her home on Korcula for the first time and was starting university in Zagreb, so on top of adjusting to university life she also was coping with daily air raids and curfew. The Hotel Manager was at his home in central Croatia, where they were bombed daily. The Second Officer was from Dubrovnik and was there during the war.

"I can't talk about it," he added, "because I can't be objective."

The other tour leader was working outside the country at the time, he said, so he was safe, but worried about family and friends back in Croatia.

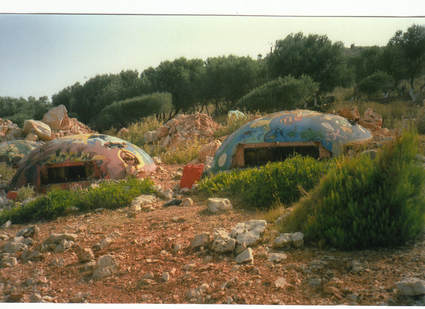

Some of the more than 750,000 bunkers Albanian dictator Hoxha had built around the country

Some of the more than 750,000 bunkers Albanian dictator Hoxha had built around the country The unfinished buildings we saw everywhere, she explained, were an investment in the future. Privatization allowed people to claim parcels of land, but they had to be working on it to retain ownership. The country was still poor, despite a decade of progress.

"After forty years under Enver Hoxha's dictatorship," she admitted, "we're still on the way from the Middle Ages to the present—not an easy or quick trip."

Thanks to Hoxha, she said, Albania became completely isolated. We drove past some of the 750,000 bunkers built around the country and coastline to "protect" Albania and its people from outsiders. Many of the bunkers had been broken and damaged and "decorated" since the dictator's death. Now, they hunkered along the rocky shore like giant multi-colored tortoises. Vast sums of money had been spent on those miles of fortifications. Why? According to Hoxha, to keep out the rest of the world, which was insanely jealous of what the Albanian people had. Since no Albanian could leave the country or have contact with anyone beyond the fortified borders, nobody could contradict him.

Sherrill, Temple of Apollo, Delphi, Greece

Sherrill, Temple of Apollo, Delphi, Greece There wasn't much that we could see in Albania then and few roads to get us anywhere, so we sailed early the next day, stopping at the Greek island of Corfu on our way to Delphi and then Athens, the end of the trip. The heat had continued to escalate, climbing as high as 111 degrees. All over Greece people had to be hospitalized and the Acropolis in Athens was closed. By the time we reached Piraeus, the port for Athens, the sky was darkened with clouds of smoke as forest fires spread across the country.

The temperatures began to drop a little the next day so the three of us could explore Athens a bit. Sherrill and I hadn't been there since 1984. The Acropolis reopened, so Tom and I climbed up to the Parthenon while Sherrill tried to stay cool below. Two days later, after watching an orange sun struggle into the grimy sky, we left for the airport.

To be continued....

Please pass the posts on to anybody else you think might enjoy them.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed