Abandoned French Colonial house

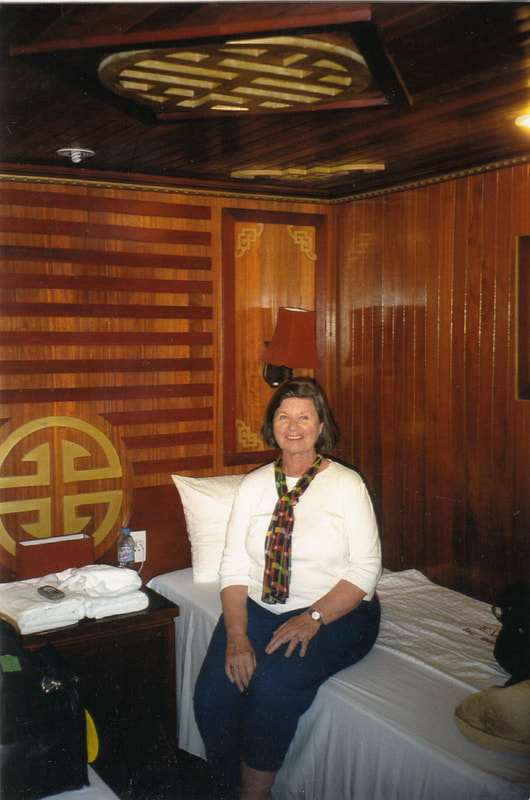

Abandoned French Colonial house Sherrill and I were surprised to see so many buildings that obviously dated back to the French and Chinese colonial periods. The ornate old architecture, with its frills and gestures to a long-vanished past, gave Hanoi a distinct charm, even when it was decaying. The government in the unified Vietnam was Communist, but the economy was capitalist, our guide told us. People often worked at several jobs, even working at the sides of streets, selling food, cutting hair, giving massages, whatever they could do.

Ho Chi Minh Mausoleum, Hanoi

Ho Chi Minh Mausoleum, Hanoi "But it's a beautiful country," the young husband told us. "And the people are the most gentle and kind-hearted you would find anywhere."

Parents on motorbikes waiting for school to let out, Hanoi

Parents on motorbikes waiting for school to let out, Hanoi  Young farmer & water buffalo

Young farmer & water buffalo  Sherrill & figurehead on junk, Ha Long Bay

Sherrill & figurehead on junk, Ha Long Bay  93 year-old betel nut chewing woman at fish farm.

93 year-old betel nut chewing woman at fish farm. On our way south to Hoi An, we stopped at a fish farm, where large cages were immersed in the water between plank catwalks and houseboats. Climbing down onto a wood walkway, we watched sea creatures hauled up in nets: monster shrimp, huge striped sea snails, crabs, a shark-looking fish, and some sea beasts that we didn't recognize. With the help of a translator, Sherrill talked with a woman in her nineties sitting on her haunches on the planks chewing betel nut.

"How long have you been chewing betel?" Sherrill asked.

"Since she was seven," the translator replied for the old woman.

"No wonder her teeth are black." I stepped closer, asking in pantomime if I could take her photograph. She nodded, then spat red betel nut juice on the planks.

The subject of the war was never far away during this trip. We stopped at China Beach, the once famous R & R location for thousands of American soldiers. It was quite an emotional experience for the woman who had entertained troops there. She walked barefoot into the surf, a tiny figure on the long beach, lost in private thoughts. Afterwards, she talked with Sherrill and me about her memories.

"The soldiers loved it when our troop was here. They took us out into the water in little boats and things. One of our girls drowned, though. I can remember it so clearly."

Turning away, she stopped talking for a while.

We passed Da Nang, which she also remembered. The entire city was a vast military base during the war, she told us. Now, it seemed to be turning into a city of high rises.

Floating village by Gulf of Tonkin

Floating village by Gulf of Tonkin  Lantern-making shop

Lantern-making shop

Several thousand people lived in small clusters on the slopes below the mountain of Lang Bin, many of them of the Lat tribe. Although the area generally was poor, they filled their lives with color. In one of the long houses, we saw some beautiful fabrics being woven on fairly primitive looms. The hands of the young weavers moved like hummingbird wings as they pulled the threads into place, their naked feet working below at the same time. At another place, we watched with fascination the complicated process of constructing beautiful lanterns from wood and silk. In the evening, we sipped rice wine while listening to folk songs and watching traditional dances around open fires—a very different experience than anything in the cities.

Political posters, Saigon

Political posters, Saigon  War Remnants Museum, Saigon

War Remnants Museum, Saigon  Sherrill, Mekong Delta

Sherrill, Mekong Delta

The next day, we rose before dawn to begin our long journey--once again staying overnight in Bangkok en route--back to San Francisco and Berkeley.

To be continued....

Please pass the posts on to anybody else you think might enjoy them.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed