One of the pleasures of exploring India is the feeling of existing simultaneously in several different worlds. There Sherrill and I were, after another marathon journey (including six hours in a transit hotel in the Singapore airport), still on California time, in the coastal city of Chennai (formerly Madras) on the Bay of Bengal near the tip of the Indian subcontinent, surrounded by Victorian-era buildings from the days of the Raj, about to explore some of the most ancient and dramatic sites in India. Once again, since I couldn't sleep, I went for an early morning walk the day after we arrived.

Great Temple. Tanjore

Great Temple. Tanjore Religion, power, and business had been stirred together into a lumpy curry during India's long history. Our exploration started with Fort St. George, built by the East India Company in 1653, and the accompanying British Anglican church, then moved on to the first Catholic cathedral in India: dueling European churches in a Hindu land? Then we plunged into the colorful chaos of a seventeenth century Hindu temple, where we watched a Brahmin priest with his sacred string across his bare chest reciting prayers, followed by a non-Brahmin repeating them in the local language of Tamil—a recent development.

Sherrill took my hand and together we maneuvered our way out. The smoke and incense were making her sick. Neither of us was comfortable among people working themselves up into such a frenzy, probably because we didn't understand where it might lead.

Villagers with rice powder medallions in front of houses for Pongal Festival

Villagers with rice powder medallions in front of houses for Pongal Festival The word "pongal," we learned, means "boiling over." We watched some pongal rice being cooked its special pot. When it boiled over, people looked to see which direction it spilled over—it would foretell their future.

After several hours in the village, we left on one of the crowded local buses, riding it to Tanjore. The bus stopped for gas opposite a big tent next to an old Catholic church. A Christian revival meeting seemed to be going on—although the area was Hindu. (In fact, I'd actually heard a Moslem call to prayer at 5 a.m. In India, now, religions seemed to weave around each other, not competing as much as co-existing—although we knew, of course, about the religious violence after Partition.)

Dravidian priest on pilgrimage

Dravidian priest on pilgrimage

While we were in Pondicherry, we saw the first of several posters urging parents to value female children, part of a campaign to stop the killing of girl babies.

"Too little, too late," Sherrill commented.

"Better than nothing," I said.

"Better than nothing? Yes."

M. G. Ramachan, Tamil movie star & politician

M. G. Ramachan, Tamil movie star & politician We also saw a bigger than life-size statue of one of India's biggest movie stars who retired to become a successful politician and then started free lunches in the schools throughout the state of Tamil Nadu—which prompted the farmers and other poor parents to send their children to school for the free food, which eventually increased the literacy level in the state to 80 percent.

Sacred cows and termite mound with Cobra "temple"

Sacred cows and termite mound with Cobra "temple" "You would've hated the narrow cliff road, sweetie," Sherrill told me when she got back that evening, "but you missed some wonderful smells!"

Backwater canal ferry pulled by rope, Kerala, South India

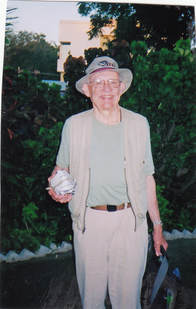

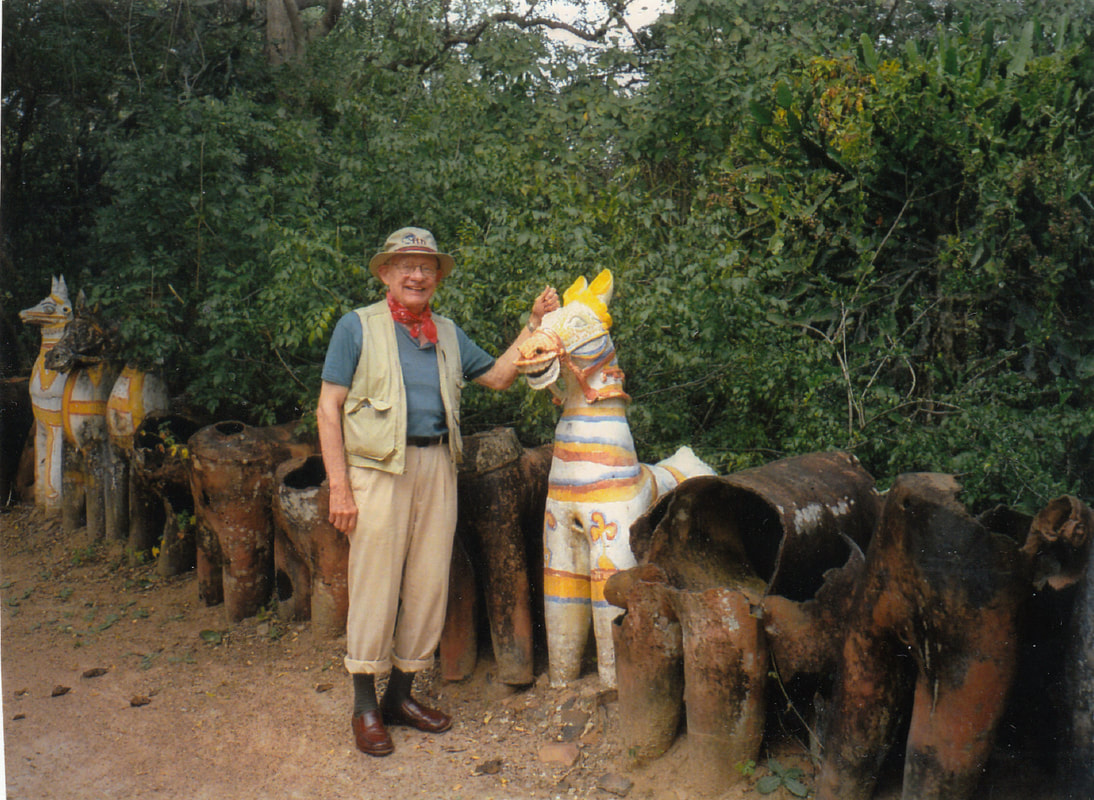

Backwater canal ferry pulled by rope, Kerala, South India  Sherrill & Bruce, South India, 2008

Sherrill & Bruce, South India, 2008 To be continued....

If you find these posts interesting, why not explore the rest of my website, too? Just click on the buttons at the top of the page and discover where they take you—including a bio, information about my four novels, along with excerpts from them, and several complete short stories.

Please pass the posts on to anybody else you think might enjoy them.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed