Sherrill & friend, Cremona Duomo

Sherrill & friend, Cremona Duomo A 25-minute train trip from Mussolini's bloated Milan station deposited us in medieval Pavia, where we discovered narrow cobblestone streets, a covered bridge, and a 14th century castle turned into the city museum. As far as we could tell, no one else was in the museum except us and a young red-haired security guard in baggy orange pants who scurried along with us unlocking doors and then locking them again. She tried to make conversation with us, despite her shaky English and my worse Italian—and the interruptions of her walky-talky—compensating with smiles for what she lacked in vocabulary. I had the feeling that she'd keep on opening and closing doors as long as we needed her to do it.

18th century wax model, science museum

18th century wax model, science museum Sadly, we had to disappoint her, since we didn't travel with a U.C. Berkeley mug.

We always felt comfortable, at ease, in Italian towns, but we especially enjoyed our evenings in Cremona, the next town we visited, when everyone—families, couples, and individuals—came out to walk. It was like the paseo that we had seen in Spain, quietly joyous and civilized. They stopped for a glass of wine and a snack, then later had dinner in a trattoria or restaurant. Why, we wondered, didn't everybody live like this?

Mincio River, Mantova

Mincio River, Mantova How could I miss them? And she was right about the daddies. Often, it was the fathers who were caring for the little kids. Italian men did seem to be good parents.

"Look." Sherrill nodded toward a young father and his two-year-old daughter barking at each other over and over after a dog had passed them. A little later, she pointed out another dad and his tiny son saying "ciao" repeatedly to a friend trying to leave them.

"Ciao!" "Ciao!" "Ciao!"

We could still hear them as we wandered down a narrow street lined with violin-making shops, passing three young musicians playing violins together, an open violin case on the cobblestones in front of them.

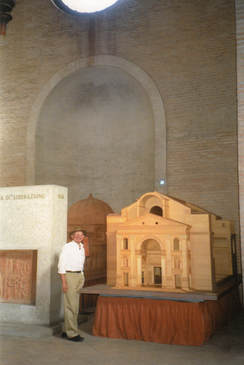

Bruce with basilica model, Mantova

Bruce with basilica model, Mantova Spontaneously, one morning, we hopped on a train south to Modena for the day because Sherrill wanted to see the Romanesque church there, but when we arrived couldn't find the way from the station to the center of town. When I asked a young local fellow for directions, he took a city map from his backpack, opened it to show us the route, insisted that we keep it, and walked part way with us to make sure we were heading the right direction. Despite our impetuousness, it turned out to be a good day.

Graduate acting the fool

Graduate acting the fool "If we hadn't missed that boat," I told Sherrill at lunch, "we wouldn't have had this wonderful meal."

"Okay, Pollyanna, if you say so."

Sirmione from the lake

Sirmione from the lake "Why not?" Sherrill asked me, mischievously.

"You see?" said the old lady. "The signora agrees."

While we were there, we also got to know a young woman from Venezuela who had lived several years in Hawaii, married an Italian, and now was happy in Italy—although it did take her a while, she admitted, to get used to the Italian way of life.

"Not like Venezuela or the United States."

Roman Forum, Brescia

Roman Forum, Brescia On the bus from Sirmioni to Breschia, however, we decided to stay there for a bit, instead of immediately going on Bergamo, as we'd planned, so we got a room in a hotel by the station, left our bags, and set out. Breschia, we discovered, had not one, but two cathedrals—a new Baroque one and an 11th century old one (Sherrill's favorite), in the Lombard Romanesque style with a domed interior plus several lower levels that descended to an even older crypt. We allowed ourselves only two days in Breschia, but made the most of them, hiking to the remains of a large Roman forum, up a steep hill to a medieval castle, and among narrow winding streets (more cobblestones) and odd-shaped piazzas. We were glad not to have missed any of it.

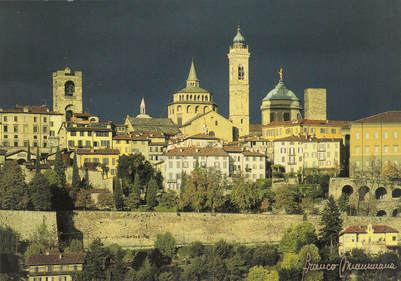

Bergamo with its defensive walls

Bergamo with its defensive walls A couple of happy incidents: When Sherrill and I slipped into a small church in the upper town to see a Titian polyptych behind the altar, the place turned out to be empty and dark. Nevertheless, we stumbled through the church toward the altar, trying to peer through the gloom at the painting. An elderly caretaker limped up out of the shadows and—instead of telling us to go away—explained in Italian that we could go behind the altar and climb the steps that the priest used. We hesitated, but he urged us to go on up.

"Si! Okay!" he said, using what I guessed was the only English word he knew.

Obeying him, we reached a spot where the light from the side windows illuminated the Titian so that we could see it perfectly. As we left, I tried to give him a tip, but he refused with a sweet smile, saying that he was glad to do it for us.

Sherrill, Lecco, Lake Como

Sherrill, Lecco, Lake Como "I have my teacher certificate," she explained, "but I want this one, too, because I believe in the Montessori approach." She was excited when Sherrill told her that our grandson had gone to a Montessori school and loved it. "Most people I talk with," she told us, "have never heard of Montessori."

She was there for six months, taking classes in both English and Italian, studying hard, hiking from a room in the lower town to the training center in the upper town except when she splurged on the funicular.

"I feel encouraged, now," she said, as we separated, "after talking with you."

Sherrill and I celebrated our forty-fourth wedding anniversary by taking the train to Lecco on Lake Como, where we walked along the lake front, had lunch at a restaurant crowded with crusty local people who apparently ate there often, toasted each other with sparkling wine, and then rode the train back to Bergamo—all very spontaneous. Afterwards, we wished that we'd asked someone to take our photograph, but at least we had the memory.

Sherrill, Bergamo Botanical Garden

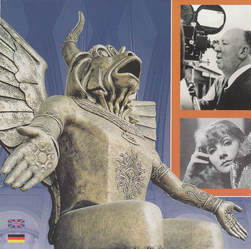

Sherrill, Bergamo Botanical Garden  Cinema Museum, Torino

Cinema Museum, Torino Started in 1863, this strange building with an elongated dome topped by a Greek temple topped with a pointed spire grew until it reached the height of 167 meters, the highest brick building in the world and the tallest building anywhere until the Eiffel Tower. Now, it housed the greatest museum in the world dedicated to the history of the motion picture—six of its floors around a central atrium, full of endless movie clips, still pictures, and more. We took the glass elevator to the top, gazed out over all of Turin—at the red tile roofs, domes, towers, palaces, office buildings—then went back down to the spiraling ramp and the history of the moving image, starting with shadow dramas.

"We can't do all this in one day," Sherrill told me, lowering herself into a chair.

She was right, so we returned the next day.

To be continued....

Please pass the posts on to anybody else you think might enjoy them.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed