Sherrill at Medieval cloister by Christopher Columbus's boyhood home, Genoa

Sherrill at Medieval cloister by Christopher Columbus's boyhood home, Genoa We'd talked about this in the past. We had traveled in Italy and France many times, but never got to either Genoa or Marseille. And although we'd been to Spain three times, we'd missed the northeast corner with Barcelona. A mop-up trip along the Mediterranean coast from Genoa to Barcelona, by way of Marseille and a stop in Montpellier in France would take care of it. We'd allow time in each city to wander and explore. And, I promised Sherrill, no driving. It would be easy and fun. Well, that prediction was mostly correct.

After a one night stopover in London, we flew to Cristoforo Colombo airport in Genoa. (Heathrow was as chaotic as ever, but once again we survived it. There was no point traveling, if we needed everything to be easy.)

19th Century Galleria Mazzini, Genoa

19th Century Galleria Mazzini, Genoa "This is the kind of day I like," Sherrill told me that evening, as we sat at an outdoor table at a small osteria hidden on a narrow hillside alley around the corner from our little hotel. "No schedule, no place we had to be."

No menu, either, but a young girl brought us delicious dishes and carafes of cheap but good red wine. Debris drifted on the cobblestone alley behind us and over nearby steps, but a little grunginess didn't kill the magic of the place. Music floated out of an open door next to the osteria: a jazz club called Count Basie. Later, four musicians wandered out and sat at the next table—one American, three Italians. We talked with the American, a saxophonist who looked like a middle-aged Matt Damon in need of a shave. As we left, Sherrill whispered that she was sure he was high on something.

"But he was good," she conceded. "Very good."

I trusted her judgment since she used to play both the clarinet and sax when she was younger and knew much more about music than I did.

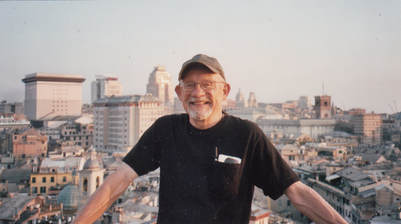

Overlooking Genoa

Overlooking Genoa Maybe what we liked best about Genoa were the people who came out every evening, strolling along the streets, dropping in at cafes, socializing. We enjoyed the city, but decided to go further afield, at least for a day, so we rode a bus to a tiny train station in the hills, where we caught a narrow-gauge two-car train that took us over steep, winding tracks into the Apennine range to the north. It was a treat to ride into the mountains, covered with green under the blue sky. As much as we enjoyed Genoa, we could breathe better up there, in the light pure air. At a village tucked into the hills at the end of the line, we got off and found a workmen's cafe, where we talked with a British couple from Wimbledon whom we'd noticed on the little train.

Marseille harbor seafood stalls

Marseille harbor seafood stalls "It's a treasure," he interrupted, blinking his pleasure.

"Steam trains are his real passion," she persisted. "He's always dragging me to ride on a train, someplace."

Norman soon was telling us about the steam trains of England and Scotland.

We liked trains, too—especially when we could gaze out at the sea and distant mountains, which was what we did a couple of days later on our way to Marseille. We'd heard that Marseille was a rough and rowdy seaport. It still was a working port, but didn't seem dangerous to us, even though our cut-rate hotel was in an area of narrow, twisting, rather seedy streets on the hills below the railway station. Sometimes, Sherrill found the hills hard for walking, but we still managed to explore the city, stopping along the way for some good meals.

Fishing and tour boats, Marseille

Fishing and tour boats, Marseille To get a closer look at the seagoing world that had made Marseille great, Sherrill and I took a long cruise through the bay and beyond, passing between the two old fortresses flanking the port entrance, then sailing among several jagged limestone islands. People once lived on at least a couple of them, since we saw several empty houses. On one island the remains of the prison of the Chateau d'If, made famous by Alexander Dumas in The Count of Monte Cristo, still stood. Then we sailed, among yachts, fishing boats, and small ships, along the rugged French coastline, broken up with small fjord-like inlets.

1909 Pathe Cinema, Montpellier

1909 Pathe Cinema, Montpellier Eventually, I learned that a crazy guy had attacked and injured a train controller on the track between Lyon and Strasbourg, prompting all the SNCF train controllers to go on strike. By late that night, oddly enough, a few trains had started up again, but not going our direction. In the morning, however, our train was one of the few moving. We never did understand the logic of what was happening, but it looked as if we'd get to Montpellier and even had hope that in a couple of days we'd reach Barcelona. The SNCF people, of course, wouldn't guarantee anything, but we knew after all these years that the only thing we could be sure of when traveling was that anything could happen.

14th century cathedral, Montpellier

14th century cathedral, Montpellier It wasn't spectacular, like Genoa and Marseille, but was loaded with charm. From its handsome Belle Epoch squares to the narrow winding streets of its medieval old town, the city quietly seduced us. For such an old city, it had a surprisingly youthful vibe. Then we learned that a third of its population was students attending its three universities. Without even trying, we found our way to the beautiful Place de la Comedie, named after an old theatre on the square, and filled with sidewalk cafes.

"It must be time for lunch," Sherrill announced.

As a matter of fact, it was, so we sat at one of the tables and, while being entertained by some youthful street performers, ate a fine lunch.

"I could sit here all day," Sherrill told me. "But I don't suppose you'll let me."

"The restaurant might not let us."

Around the corner, we discovered the headquarters for the French publisher Gallimard, which was celebrating its one hundredth anniversary with an indoor-outdoor exhibition of its history and the authors it had published, from Gide and Malraux to Sartre and Beauvoir, to Hemingway and Faulkner to Ionesco and the author of the Curious George picture books about a mischievous monkey.

Despite the train controllers' on-again, off again strike, two days later we were in Barcelona. We were lucky, our trains went through, although many did not. When we arrived in Figueres, where we had to transfer, the Barcelona train even was waiting on the same platform.

Sherrill and Bruce on cruise from Barcelona, Spain

Sherrill and Bruce on cruise from Barcelona, Spain "You never know who you'll meet," I said, as Sherrill and I walked down the Ramblas to the waterfront.

"It wouldn't be a surprise, if we did."

We saw no tourists in Montpelier and surprisingly few in Marseille, but Barcelona was clogged with them, including a team there for some event—lanky young men in white suits who popped up everywhere. Although Barcelona looked nothing like Venice, in one way it felt similar: magnificent and beautiful, but as if we'd arrived late at the party. Despite that, we enjoyed the city. Its weirdness appealed to us.

Gaudi's Casa Batllo,

Barcelona

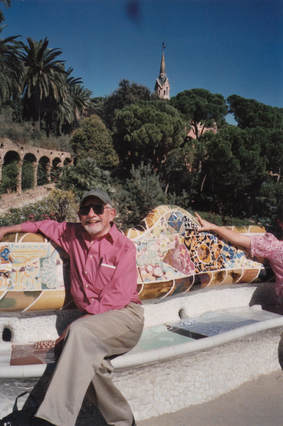

In Gaudi's Park Guell, Barcelona

In Gaudi's Park Guell, Barcelona A splendid day wandering among the dark, narrow streets of the Gothic Quarter and in the Picasso Museum reminded us that although many people are talented very few are geniuses. The astonishingly skillful and sophisticated work that Picasso produced even as a young boy, we saw, was the foundation for his later experiments. Later, while Sherrill rested, I wandered through the Dali museum deep in the Gothic Quarter—two floors of paintings, drawings, and sculptures—tantalized by his ability to paint absolutely realistic objects and scenes that unexpectedly slid into the absurd. His work gave the impression that he could do anything—if he chose. Sherrill joined me for dinner at the 4 Gats restaurant in the Gothic quarter, the same place once frequented by the young Picasso, Gaudi, and other artists. Walking through the curved arch of the entrance did feel like stepping into a lost, enchanted time.

We'd been told that we couldn't visit Barcelona without going to the basilica and monastery atop the saw-tooth ridge of Montserrat. The darkened wood statuette of the Virgin and the complex around it didn't particularly interest us, but we rode the train and cable car to the top. We conceded afterwards that the whole experience, including the all-boy choir and the crowds of pilgrims, was fascinating, in its way. We watched and listened, hopefully respectful observers, but definitely on the outside. Human beings were complex creatures, we saw once again, but that didn't mean that we had to share either their beliefs or experiences.

Dali Museum, Figueres, Spain

Dali Museum, Figueres, Spain The museum/theatre (as he called it) was, itself, a vast work of art, as well as filled with the world's largest collection of his art. At least half of the time, if we looked closely at a work we discovered that it wasn't what we thought it was at first. Either it had changed or our perception of it had changed. To keep us off guard, he even had slipped in genuine paintings by masters ranging from El Greco to Marcel Duchamp. The jokester artist never quit, never backed down.

To be continued....

Please pass the posts on to anybody else you think might enjoy them.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed