Sherrill, 2013

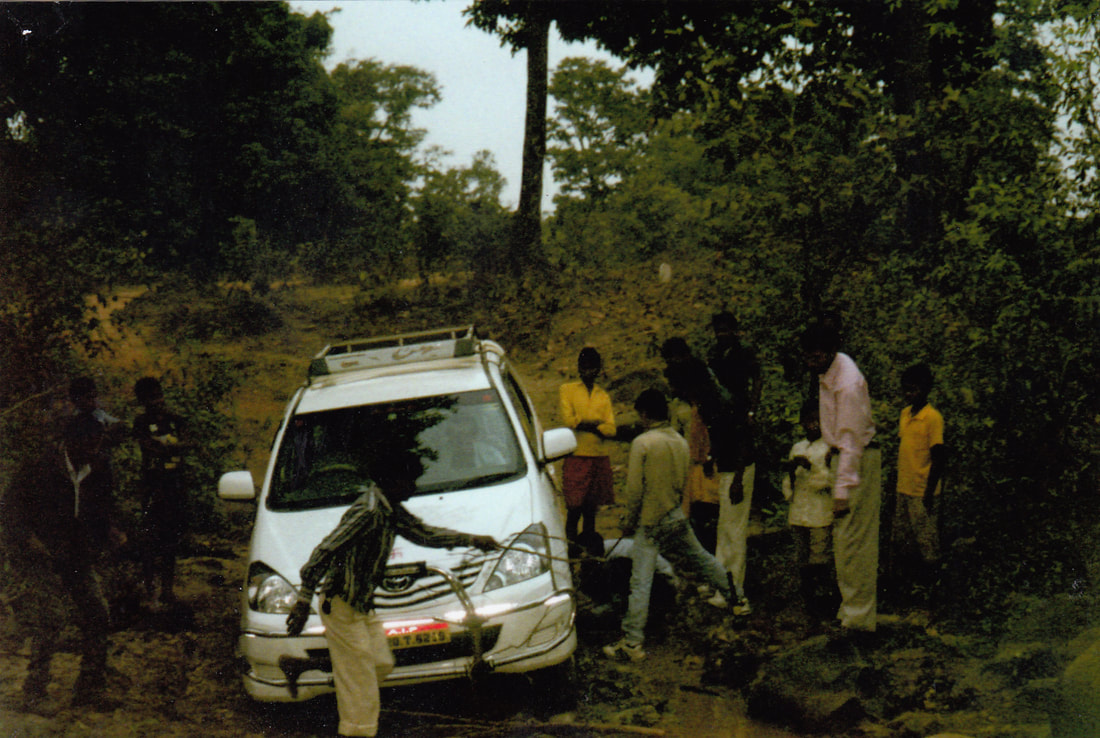

For four hours, our SUV bounced and lurched over narrow, crumbling, mountain roads to a remote village in a forested area where the people still lived as they had hundreds of years ago. When I checked the car as we got in, I couldn't find any seat belts where Sherrill and I were going to sit. I asked our handsome, dark-skinned young guide about it. He just smiled.

"We never use them."

"Well," I told him, "we're not going anyplace without them."

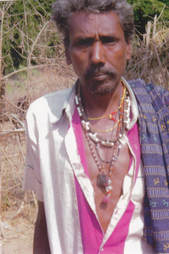

Tribal village man showing

charms to keep away

evil spirits

Bathra tribe villagers

"Probably back home drunk on mahua," our guide said.

This was a fermented drink made from a local tree, although they also brewed beer from rice or palm sap. As in many tribal societies, the village women did most of the work.

Sherrill shook her head. This pattern may have been traditional, but that was no reason to approve of it.

Tribal man collecting sap to make

an alcoholic drink

* * *

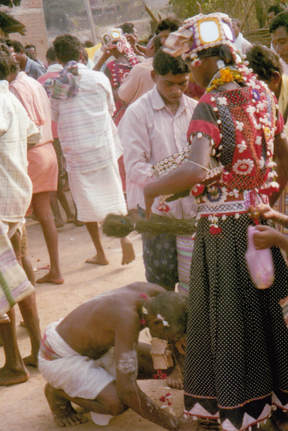

Village shaman about to purge "evil spirits" from his patient

Village shaman about to purge "evil spirits" from his patient Shoulders hunched forward, the shaman chanted prayers while burning incense and arranging orange marigolds. He was trying to communicate with some of the hostile spirits who roamed beyond the material world and enjoyed tormenting human beings. Behind him, wearing only an orange dhoti, waited the village man he hoped to cleanse of spirits that had "possessed" him.

Shaman & patient beginning purge of "evil spirits"

Shaman & patient beginning purge of "evil spirits" The shaman chanted louder, scattering more rice grains over the afflicted man, who doubled over, legs twitching, clutching his abdomen. The shaman and his helper could hardly control the flailing, retching, patient, his legs now doubled back under his writhing body. He might have vomited blood (as people say sometimes happens) or have bitten his tongue, but blood there was. Carefully, the shaman straightened the man's twisted, knotted legs and, at last, the man lay flat on the dirt, whimpering. Slowly, with assistance, he managed to stand. Whether or not evil spirits had been expelled from him, we had no way of knowing.

* * *

"I feel like a moth on a pin under a microscope," Sherrill whispered.

Preparing for village festival ceremony

Preparing for village festival ceremony As drums beat louder, one of the almost naked priests thrust his banner into a bamboo framework, then, moaning, let himself flow into the rhythm of the drums, rocking his head back and forth, body swaying as he slid into what seemed to be a self-induced trance. His eyes rolled, his mouth opened and closed, he fell and his body spasmed and convulsed on the hard-packed dirt. Beating himself with a flail, thrashing his bare back furiously with the many small whips of the flail, he fell to his knees, just a few feet from Sherrill and me. He seemed to be trying to rid himself of his physical body—or to drive evil spirits from it. I wondered how much more this thin brown-skinned man could take of this self-exorcism. Eventually, two other men in dhotis took the flail from him and led him away, despite his writhing and struggling.

One by one, each of the ten priests hurled himself into a trance that culminated in frantic flailing of his flesh until he was dragged away. These rituals, we were told, probably came with these tribes to the Indian subcontinent from Africa thousands of years ago. Would they, I wondered, survive in a changing world?

* * *

Youth being prepared for Coming of Age ceremony

Youth being prepared for Coming of Age ceremony As each youth went deeper into his trance, his body shaking, a priest completely covered his head with a white cloth. When it was removed, a needle-sharp bone spike now pierced both of his smooth brown cheeks, running through his mouth. How this was done without us seeing, I don't know, although we were only five or six feet away. Supposedly, because he was deep in his trance, he felt no pain. We didn't see any blood, either. He was lifted onto a decorated throne and carried in circles around the ceremonial area.

After all of the young men had been transformed and enthroned, they were carried in a procession through the gate, accompanied by the musicians and the rest of us, and through the market, avoiding stray cows, piles of small purple eggplants, green okra fingers, and baskets of tiny red tomatoes. Now, the village women could see the transformed youths on their dazzling thrones.

* * *

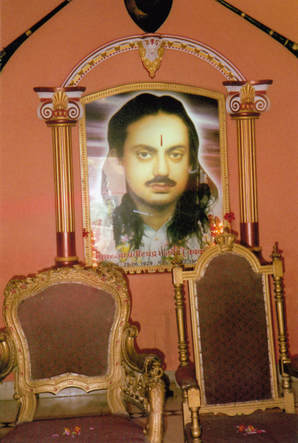

Throne room portrait of young Maharaja

Throne room portrait of young Maharaja Our clever young guide had arranged for us to visit one of the reigning royal households in Eastern India. Although India was a democracy, the young unmarried Maharaja of Y still thought of himself as a king. He was away on royal business, so we were received by his sister, the princess, a poised young woman of twenty-five. The sprawling white palace, with its columned arcades, wide terraces, arched windows, and ornate architectural details was built early in the 20th century, but designed to look older. One wing had been turned into a school, other sections also put to new uses. The entire walled complex had been swallowed by a growing provincial city.

The princess strode into the high-ceilinged room wearing a mix of traditional and Indian styles, a smart phone in one hand, greeted us, and urged us to feel "at home." She told us about her family's colorful and noble history and how hard her brother worked for his people. Sherrill and I looked at each other, but of course didn't say anything.

"They love him," she said. "When he sits on his throne in the public audience room downstairs, many come—not because they want favors, but because they want to see their beloved king." She gazed without irony at each of us. "They are happy with their lives and everything my brother does for them."

* * *

Our Hyderabad hotel required everyone entering the building to pass through an airport security style screening and all vehicles driving onto the grounds were checked for bombs, mirrors even slid beneath each car, truck, or bus. The new shopping centers and some famous historic sites also required security checks. This seemed to have become routine after the deadly bombings in Mumbai a few years earlier. Two weeks after our return from Eastern India, two bombs exploded in Hyderabad, killing sixteen people and wounding scores.

However, the lasting impression of this part of India wasn't only of violence. We also remembered the mother tiger exhausted from her effort to feed her cubs, colorful harvest festivals, private morning rituals along the streets of Kolkata, students in a village school, and a barefoot man wearing only a ragged dhoti sleeping on the side of a flower-strewn overpass above the Kolkata flower market, a chaos of fading petals for his pillow.

End of Part Two, Eastern India.

If you find these posts interesting, why not explore the rest of my website, too? Just click on the buttons at the top of the page and discover where they take you—including a bio, information about my four novels, along with excerpts from them, and several complete short stories.

Please pass the posts on to anybody else you think might enjoy them.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed