Sherrill, Ukraine, 2013

Odessa: "Birth of the New Era"

Odessa: "Birth of the New Era"  Sherrill & Tom, Pushkin statue, Odessa

Sherrill & Tom, Pushkin statue, Odessa The 200 year-old Odessa catacombs that hid resistance bands during World War Two could have been from another old movie, but even more fascinating to us were the great caves at the Black Sea military port of Sebastopol, still the biggest maritime base for the Russian and Ukrainian fleets—and Russia's only warm water port. Deep underground, we explored huge caverns that had been a secret nuclear submarine installation during the Cold War, even a vast underground dry dock for submarines. Although these caverns no longer were used, the port still was an active military base, so we weren't allowed to take photographs outside the caves.

Sailing on the Black Sea and up the Dnieper River through the heart of Ukraine was the best part of the trip for Sherrill. The stops along the way to visit various towns, churches, palaces, and historic sites were interesting, but moving along the cloud-speckled water under the transparent blue sky, watching the variegated colors of the shore pass by, feeling the caressing motion of the four-deck river ship, made her the happiest. The river flowed down to the sea, but—passing through five locks—we chugged against the current all the way up to the 1,500 year-old capital city of Kiev, called in Ukraine "the Mother of Cities."

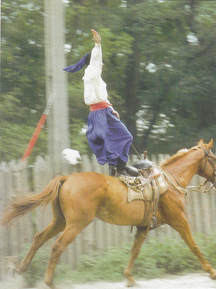

Cossack horseman

Cossack horseman The names of the cities along the way sounded as exotic as the sights we discovered in them. Two that I especially remember: Kherson , founded by Catherine the Great and home to the fabulous Cathedral of St. Catherine, and Zaporozhye, where we discovered Neolithic goddess figures displayed in a park and where the Cossacks stunned us with their skillful, frantic, insane horsemanship. Every town had raised a huge monument to the Great Patriotic War against the Nazis and Lenin's stolid bulk was on display more often than we'd expected.

They remembered that although the Ukraine was considered the bread basket of the Soviet Union, 7 million of its people, mostly children, had died of malnutrition because Stalin insisted that the grain it produced be exported. Peasants were shot if they hid grain for their families. One old lady in Kiev, her little body hidden under her kerchief and raincoat, constantly rearranged her treasures to tempt people who might pass—bulky socks and scarves that she'd knitted, an old table lamp, several ashtrays of varying sizes and shapes, dishes and glassware that had survived from once complete sets, small figurines, a bust of Lenin, Communist medals. We didn't need any of it, but Sherrill and I wanted to give her a few hryvnia.

"Okay," Sherrill told me, tugging at my shirt collar. "but not Lenin."

"Babushka" selling flowers by old tram, Kiev

"Babushka" selling flowers by old tram, Kiev Walking along the city streets and boulevards, sitting in a basement cafe, exploring shops and museums, we were struck that the people of Kiev dressed almost entirely in black, often black leather (or faux leather) jackets and dark blue jeans. For the most part, the clothes were of cheap fabrics and badly made, but the large men we saw standing in small groups near expensive black automobiles wore the real thing. In smaller cities we'd visited, we'd noticed thirty year-old Russian Lada cars, often decorated with dents and rust, but here we saw shiny Mercedes, Porsches, and BMWs, although ordinary people crowded onto antique buses and streetcars. Kiev was a city of contrasts, rich or poor, new or old, powerful or weak, ordinary citizens or those with "contacts."

Maybe a woman we met outside a small chapel near the Yalta waterfront best symbolized this optimistic spirit. When we peered through the open door into the ornate Orthodox chapel, she rushed out, showing her single tooth and gums in a smile and asking in simple English where we were from. When we said America, she grinned even more broadly.

"Amerrrica!" she shouted. "New Yorrrk!"

And she told us that once upon a time she had danced at Radio City Music Hall. Did she expect us to believe that she'd been a Rockette in her youth? Well, why not? Her husband was dead, now, and her children were gone, but she insisted that life was good.

Woman selling aprons, Kiev

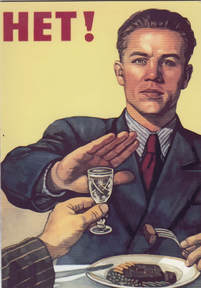

No vodka! poster, Kiev

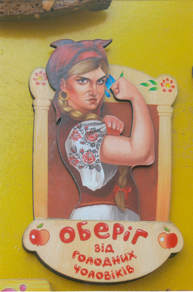

"Taking Care of the Hungry Man"

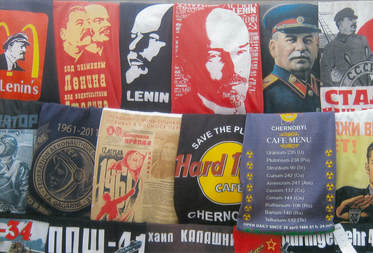

Tee shirts for sale, Kiev

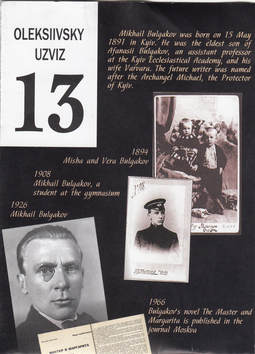

Tee shirts for sale, Kiev Several times, talking with people in Ukraine, we heard how the former Communist leaders quickly dominated the new government and snatched control of major industries and utilities during the privatization process—embracing the future by using tricks from the past. This was an irony that the great Ukrainian satirist Mikhail Bulgakov would have appreciated. Bulgakov struggled against Soviet censorship though his whole career. His greatest work, the novel The Master and Margarita, wasn't published until 26 years after his death in 1940.

Before we left Kiev, Sherrill, Tom, and I gave ourselves a splendid, typical Ukrainian dinner at a hillside restaurant in a wooden 19th century building with traditional scalloped trim that looked out over much of the city. It probably was overpriced, but still was an enjoyable way to say goodbye to Kiev and Ukraine. I'm not sure which of us ordered what, but I remember green borscht with nettle, dumplings with mushroom sauce, goose pate (that was Sherrill), duck breast, and Chicken Kiev. Plus a local wine and to finish local cheeses and Cake Kiev.

For more than 20 years, Ukraine had struggled to get its arms around its new independence—the first time in its long history that it had been independent. Or was it independent? That was the question that many Ukrainians were asking. Was the country a province of Russia—or was that where it was headed? Despite the corruption and threats, the Ukrainian population seemed determined to pull through, this time.

If you find these posts interesting, why not explore the rest of my website, too? Just click on the buttons at the top of the page and discover where they take you—including a bio, information about my four novels, along with excerpts from them, and several complete short stories.

Please pass the posts on to anybody else you think might enjoy them.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed