"This is where you'll write," Sherrill told me, hand on a small blue table with a portable typewriter by the single window in the tiny dining room of the one bedroom apartment we'd rented in Oakland.

The tall nineteen-twenties building, embroidered on the front with stucco flowers and leafy scrolls, faced Lake Merritt, but our two and a half rooms plus bath and kitchenette were tucked into a back corner. Still, it seemed luxurious after Sherrill's studio apartment and my one room in Berkeley (across the street from each other—this was 1964, after all). For some reason I couldn't figure out, she cared about me and my writing. She'd proved this the year before when she typed an entire novel for me (pre-computers).

We soon established a routine: I was up early three mornings a week to watch lectures on classic Russian fiction on our black and white television and every morning by eight was at my Royal machine alternately working on a novel or a short story, both set in San Francisco's North Beach. Sherrill was back at the Oakland library, ordering children's books and telling stories. In the evenings and on weekends, we read or watched television. Sometimes, she posed while I drew or painted her.

Then, one day as we returned from shopping, she announced that she was pregnant.

Sherrill had medical coverage for both of us through the city of Oakland and would be able to take maternity leave with pay. As far as we could see all was well with the world.

Flash forward six or seven months: Sherrill was ostentatiously, gorgeously pregnant, I had more or less finished both the story and the novel, and we were going shopping. Our objective: buy her a handsome, business-like dress to wear to an interview for senior librarian. Not so easy, we discovered, for a young woman so very pregnant. Maternity dresses came in cute, charming, fussy, sweet, but not business-like, not simple and sophisticated enough to inspire confidence in a woman's management abilities. Apparently, a woman wasn't supposed to aspire to such realms when she was with child.

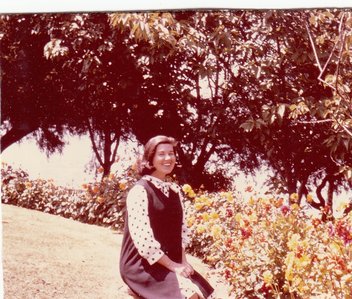

At last, after exploring almost every likely shop in the East Bay, we found the perfect outfit, a white under-dress with long full sleeves and a business-like bow, with discreet black polka dots, and black tunic that covered it except for the sleeves and bow. It definitely gave her the needed executive look. And she still had a week before the interview. I even took a photo of her wearing it in the park by Lake Merritt. Good thing I did, because that was only time she wore it.

The night before the interview, she woke me up. The baby was about to be born. I called a taxi and we were off to Kaiser hospital. All night and into the morning, Sherrill, the doctor, and the baby maneuvered while I waited below. In those distant days, fathers were not allowed upstairs. I had nothing to do but read most of the 600 pages of the Letters of F. Scott Fitzgerald. Finally, a nurse took me up to meet Sherrill and the baby coming out of the delivery room. Sherrill looked exhausted, but well. The tiny infant cuddled next to her was beautiful, although it seemed to have fringe growing on its ears.

"We got our girl," Sherrill told me as I kissed her.

Back at our apartment, I called the Oakland library department, to tell them why Sherrill wasn't at the interview.

"When can she have a make up interview?" I asked.

"She can't."

"But the baby was two weeks early. That's not Sherrill's fault. It's only fair that you let her have the interview later."

"We never do that. There's only one interview." The woman's voice suggested Inspector Javert with a southern drawl. "We pull a panel together once. Candidates all have to be there."

I argued, but the woman was stubborn. No second chances. No apology.

"Then when's the next scheduled interview for Senior Librarian? Six months? A year?"

"Never. It won't be necessary."

More arguing, more stubbornness. Another message that pregnant women shouldn't have career aspirations? Today, I might threaten to sue, but in 1965 it didn't occur to me.

Sherrill decided to name the little girl after Simone de Beauvoir. Looking out the hospital room window as we were leaving, she saw a giant rainbow—it was only the Rainbow Car Wash across the street, but she was sure that it was a good omen.

I plan to add a new installment to this blog every Monday. I hope you'll check back.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed