Freedom of speech is an irrelevant concept, as far as these angry individuals are concerned. Of course, this isn’t new. Intolerance has been around for millennia. Now, however, these individuals feel they have the right to eliminate those who dare disagree with them. Nazi Germany, the Soviet Union, and other dictatorships had their methods of eliminating open disagreement, but today anybody might decide that you should die because you’re a danger to his—or her—beliefs.

Will they succeed in stopping free expression? Even the Nazis and the Communists eventually failed.

The Communists were still in power. The year: 1988. The place: the territory and city of Kaliningrad, named for a buddy of Joe Stalin. My wife and I were exploring the bleak, gray remains of several centuries – none bleaker or grayer than those produced by the Soviet Union.

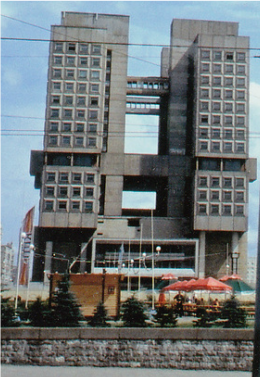

Kaliningrad, Konigsberg under the Prussians and Germans, is Russia’s only Baltic port that never freezes over. For decades part of the USSR, it’s separated geographically from the rest of Russia. After World War Two, the German survivors were driven out by the Soviets and the German language replaced with Russian. Much of the old city was destroyed and replaced with typical monstrosities of Soviet architecture. Even the Prussian Royal Palace was displaced by the later abandoned House of Soviets, a huge structure of remarkable hideousness.

The middle-aged woman showing us around Kaliningrad shuffled gloomily from site to site, giving us the official explanations. Then, as we said goodbye, I handed her the fat paperback copy that I’d just finished reading of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s epic The Gulag Archipelago, about the Siberian prison camps of the USSR.

“For you,” I said, putting the dog-eared paperback into her hand.

“For me?” she cried, clutching the volume to her chest, then quickly lowering it discreetly, almost hiding it. “Oh my! Solzhenitsyn! For me!”

All books by Solzhenitsyn were forbidden in the Soviet Union, even in this outlying territory of Kaliningrad, but I hadn’t anticipated such an emotional response for the gift of a well-used paperback – and in English translation, at that.

Almost in tears, the woman hugged us and said goodbye as we boarded the boat that would carry us on the rest of our journey. I still see her, in that shapeless patterned dress, long gray sweater, and down-at-the-heel shoes, standing on the dock as we pulled away, holding the hefty paperback as if it were box filled with rare treasures.

Today, it’s hard to imagine the excitement a physical book could create, the thrill of holding in one’s own hands a volume that was yours, that you could read, share, annotate, love. I wouldn’t have been able to pass on a Kindle to that sad woman, even if it had existed in 1988. It’s a different world, today, connected in different ways. Maybe it’s better, now, as words fly across the globe in many different formats. Tweets, blogs, Facebook posts, emails, text messages, and more keep us constantly, relentlessly, joined together.

In some ways, it may be more difficult these days for dictators to ban literature and ideas that they don’t like, but governments, religious leaders, and giant corporations still are busy “protecting” us from all truths but theirs. Where this evolution may take us is frightening to think about.

Words have great power, as that woman on the dock in Kaliningrad knew. If words are free and able to communicate ideas, emotions, hopes, dreams, fears, ambitions, the entire spectrum of the human mind, maybe we’ll be okay. Maybe.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed