I remember my father sitting at our oilcloth-covered kitchen table with a shoebox in which he kept the bills. Every week, he worked through that box, deciding which bill to pay, which he could ignore, which needed something on account. There was no way he’d pay all of them, or even keep all the creditors happy, and the struggle grew worse as Christmas approached.

Five days a week, before I was out of bed, he drove off in his old Plymouth coupe, on his way to work. Boring, filthy work. Work that battered his body, scarred his hands, and left him exhausted. Work that he’d done for decades, in one city or another. Work that could drive a guy nuts. Maybe, I sometimes thought, listening to him racing the engine before he roared down the street, it was driving him nuts.

I remember the year my Mom was hoping for television set for Christmas. We were the only family in our neighborhood who didn’t have a television, but a TV set didn’t fit into that shoebox. A new television that I admired in a store window cost $371. Fifteen bucks fed the four of us for a week. This was before credit cards, but most folks bought their TVs on time. Dad refused to get into debt more than he was.

“Why should I pay two weeks salary,” he demanded, “so you can watch some idiot named Red Buttons dance a jig and make stupid noises?”

Dwight Eisenhower was president, then, and his Secretary of Defense, Charles Wilson, the former CEO of General Motors, had stated, “What’s good for General Motors is good for the country.” Except that maybe it wasn’t. Corporations were making out like bandits during those years, but people like my Dad were still having a tough time. We never owned a house, never had a new car, never could be sure that the shoebox of bills wouldn’t explode in my father’s scarred face.

It was clear to me that we weren’t going to get a TV that year, and I didn’t expect a bike, which was the only other thing I wanted, so Christmas didn’t mean a heck of a lot to me. Christmas Eve, I got up to go to the toilet and caught my father in his thermal underwear crouching by the little Christmas tree, putting together a prefab stamped-tin doll house, its Sears box beside him.

“Going to the bathroom,” I said.

“Well go ahead, then get back to bed before you wake your sister.”

I was glad that she was getting a doll house, but it made me feel even worse. That doll house wasn’t nearly as expensive as either a bike or a TV.

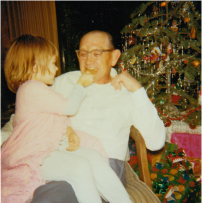

But the next morning, a red bicycle stood in front of the Christmas tree, beside the doll house. Closer inspection revealed that the bike was secondhand, a coat of scarlet paint not quite covering its original blue paint, but that didn’t matter to me. He always did the best he could – and sometimes worked wonders with that shoebox. Maybe he couldn’t pull a tiger out of it, but from time to time he managed a rabbit or two. And eventually he did find a television there.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed