The violence may have been in the distant past or very recent. When my wife and I first visited London, the city still showed scars from World War II. Walking out the Strand, we passed two of Christopher Wren’s little churches that were still empty black shells from the Blitz. Farther afield, we saw the remains of factories and warehouses bombed during the war. Today, the East End and Docklands are London’s hot new districts, spectacular modern structures rising where bombed docks and warehouses stood as reminders of the most horrible war in history.

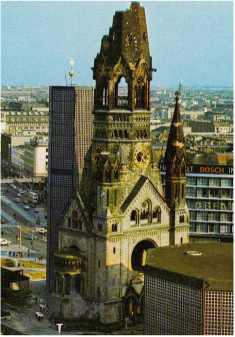

When we visited divided Berlin a few years later, we knew that the shiny modern buildings of the western sector stood where the old city had been bombed. On the main drag of Kurfurstendamm, the blackened central tower of the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church, destroyed in 1943, still stands as a reminder of the war. On the other side of Checkpoint Charlie, when we explored East Berlin and Museum Island, we saw countless bullet scars on the old stone buildings. The great empty square of Alexanderplatz, once the busy heart of prewar Berlin, told its own story of total war.

All across the Soviet Union, we encountered memorials to The Great Patriotic War, as the Russians still call World War II. It’s almost impossible for us to grasp the carnage the USSR suffered. The 872 day siege of Leningrad killed some 1.2 million people, the siege of Stalingrad at least 1.4 million. Huge areas of those cities are filled with Soviet-era apartment blocks, hideous but necessary to house the homeless millions after the war. When we visited Minsk, now the capital of Belarus, we saw almost no buildings from before the war. The USSR as a whole lost at least 20,000,000 people.

Warsaw and Gdansk in Poland also were flattened during the war, although both cities have been rebuilt, sometimes superficially reproducing the outward appearance of the old cities. The facades, we discovered, may be copied from old photographs, but step through the door and you’re in a modern building.

When we visited Egypt in1997, we stopped to look at the temple of the great female pharaoh, Hatshepsut. The next day, a group of Egyptian militants massacred 58 foreign tourists and several others trapped in the same temple. The attack was carried out by a group that hoped to destroy the tourism-based economy and build anti-government feeling. We were accompanied by armed soldiers for the rest of the trip.

Back in Cairo, I ventured out on my own, exploring the narrow streets of the old city, leaving behind my camera and trying to blend in with everyone else. I felt quite safe, wandering among the neighborhood people, street vendors, and shops. The holes in the pavement seemed more dangerous than any human beings. During the years since then, the Egyptian tourist industry has been devastated, contributing to increasingly violent social and political unrest and aggravating the conflict between religious conservatives and more liberal secularists.

During the weeks we spent exploring Syria a few years ago, we fell in love with the people and country. Although huge menacing posters of the president loomed everywhere, the people we met were welcoming, generous, and honest about their lives. When we visited the once beautiful city of Hama, we saw lingering evidence of the massacre of 1981, when 25,000 died when Hafez-al-Assad put down an uprising. Since the recent rebellion against his son began in 2011, many of the historic and cultural treasures we visited have been destroyed or badly damaged, including UNESCO World Heritage Sites such as ancient Palmyra and Aleppo’s vast covered souk and great Citadel, and countless human lives lost and ruined.

While visiting eastern Turkey, we met Kurd refugees who had fled Iraq just to the south. They and their children didn’t mix with the Turkish Kurds and the children weren’t allowed into the schools because they didn’t speak Turkish. Several times a day, groups of low-flying planes roared past overhead.

“They’re going to Iraq,” we were told. “From a U.S. airbase near here.”

What could we say?

When we spent three weeks in Ukraine in October 1913, we heard many times that people were unhappy about the widespread corruption and the income gap between those in power and everyone else. We certainly saw evidence of both, but didn’t expect the dramatic protests that soon erupted. Now, the Crimea has been wrenched away from Ukraine and pro-Russian rebels are trying to rip apart the country further.

Today, there are no guarantees anywhere. In our time, almost every city we’ve visited – from Mumbai to London to New York City, to Damascus and Rangoon and most recently Paris -- has experienced violence, ranging from bombs in subways to attacks on hotels to random shootings.

Exploring the world is becoming a series of close calls, but maybe if people continue traveling and meeting each other and communicating, and then go home and tell what they’ve seen and learned, these exchanges can help bring understanding and eventually peace.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed