The road ahead, they all admitted, was not going to be smooth, but they believed that with time they would emerge as a functioning democratic nation with a stable and growing economy. Sometimes, it was hard for me to understand how they could believe this so passionately.

Looking from our hotel room window, sitting in a basement café, walking through morning crowds, we were struck that most people in Kiev dressed in black. Mostly, the clothes were of cheap fabrics and not well made, despite the elegant designer clothes displayed in some shop windows. The large men we saw standing in small groups near expensive black automobiles, however, wore pricy leather coats. In smaller cities, we noticed many thirty year-old Russian Lada cars, usually decorated with dents and rust. In Kiev, we saw foreign imports, Mercedes, Porches, and BMWs, for the powerful few, but most people crowded onto the cheap buses and subway trains (only 3 hryvnia a ride, about twenty cents). Despite all this, we often were told that “Ukrainians are optimists.”

Life, they admitted, isn’t easy, but “we’ve been through so much that we are used to coping. We know that life will get better. It just takes time.”

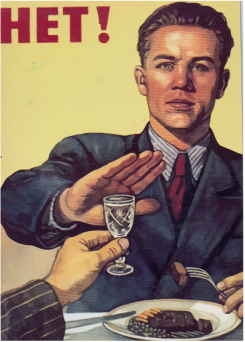

Independence from the Soviet Union in 1991 created hope for the future, but also enormous hardship. The change was especially hard for men, women told us. Suddenly, many of them had no jobs and couldn’t support their families. Women, able to adjust to change better than their men, stepped in, taking any available jobs, frequently becoming the major providers in their households. This drove the men to drink more than ever. We saw posters urging men to say no to drink, but the campaign didn’t seem to be working. The average Ukrainian male died before he reached sixty.

Working women were visible everywhere, often in low level jobs or selling whatever they had managed to scrounge together. For generations, the babushka has been a symbol of both Russia and Ukraine: the middle-aged or older woman who does whatever she can to keep herself and her family alive. We saw them sweeping leaves in parks; sitting guard in museum galleries; peddling fruit or vegetables; selling beer, vodka, cigarettes, and lottery tickets; collecting tickets; scrubbing floors.

Younger women, savvy about technology, fluent in foreign languages, and flexible enough to cope with a changing world, were moving beyond old stereotypes and seemed able to find better paying jobs. Young women, as well as young men, worked in the hotels, banks, and high-end stores, but many older Ukrainian men shuffling along on the streets and selling trinkets at small tables seemed to be suffering from shattered morale.

“This is a serious problem,” a woman told me. “Women do more and men do less.”

Unless, I suspected, they managed to become part of the mafia-like groups that seemed to lurk everywhere.

After centuries of being controlled by other countries—Poland, Russia, the Austro-Hungarian empire, the Nazis, and the Soviets—Ukraine seemed to be able at last to determine its own future, if it could overcome economic stagnation and the corruption that came with it. Maybe the Western nations should have given it more aid, just the Marshall Plan after World War Two helped Europe to rebuild.

The Ukraine was so desirable because of the rich black soil that made it the bread basket of Europe. The land fed whatever country occupied it and much of Europe beyond. World War Two was notoriously hard on the Soviet Union, including the Ukraine. At least twenty-eight million Soviet soldiers and civilians died during what they still call The Great Patriotic War. Every Ukrainian town and city boasts at least one monument honoring those who died fighting the Nazis. Many cities in Ukraine were devastated by battles and bombs. The economy never really recovered—a situation aggravated by Soviet central planning.

Finally, the collapse of the USSR gave the party heads in Ukraine the chance to declare independence. However, the privatization of businesses and industries that followed meant that a few individuals acquired the major assets of the country. The rich got richer, the rest got leftovers.

In spite of all that they’ve suffered, people told us that they were hopeful about the future.

“We see progress,” they said, “however slow it may be.”

Maybe an old woman we met outside a small chapel near the waterfront in Yalta best symbolized this spirit. When we peered through the open door into the ornate Orthodox chapel, she rushed out, showing her single tooth and gums in a smile and asking in simple English where we were from. When we said America, she grinned even more broadly.

“Amerrrica!” she shouted. “New Yorrrk!”

And she told us that once upon a time she had danced at Radio City Music Hall. Did she expect us to believe that she’d been a Rockette in her youth? Well, why not? Attractive young women often made their way to America. But she had returned to her homeland and seemed to be cheerfully accepting her present life. Her husband was dead, her children were gone, but she insisted that life was good and would get better.

I think about her, from time to time, and wonder how she is doing and whether or not she still feels so optimistic.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed