Sherrill on the Spring Wild Flower Express, 2016

Sherrill on the Spring Wild Flower Express, 2016 The following spring, we joined a garden club trip visiting Bay Area gardens and nurseries and later our daughter and son-in-law took us on a North Bay trip riding a restored old train through sea-like fields of wild flowers, their blossoms tossing on waves of wind-blown grasses. Sherrill enjoyed those excursions, but insisted that she wasn't finished exploring the larger world.

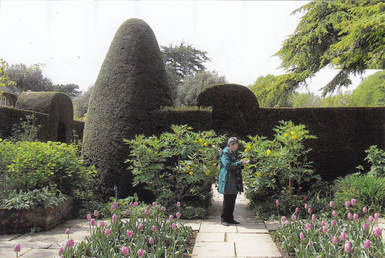

Sherrill on Garden Club tour

Sherrill on Garden Club tour We weren't traveling, now, but we still were seeing family and friends and occasionally went out to a play. When she felt like it, we worked together in her garden.

"Look," she said, one evening, after several months, "I want to go someplace."

The tour began in Phoenix, the desert city named after the beautiful bird that never died, that forever flew ahead, scanning the horizon, exploring distant worlds, the bird that symbolized our ability to extend our lives by opening up to the world around us—and even beyond.

"Nothing stays the same," I commented.

"Not even us, sweetie."

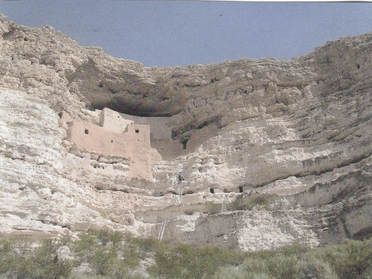

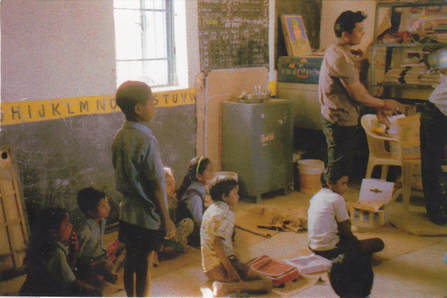

Montezuma's Castle, Arizona

Montezuma's Castle, Arizona "I don't want to spoil it for you," she told me.

"Don't worry, you're not."

"Well, I don't want to," she insisted, tugging at the hairs on the back of my neck. "And you need to use your razor back here."

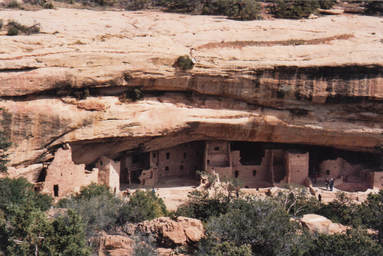

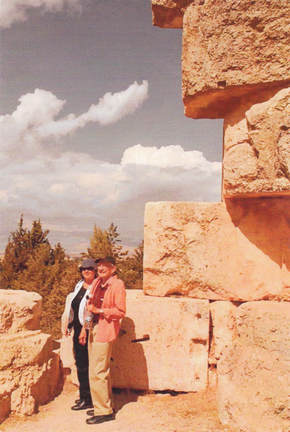

We could see why the five-story complex of 20 rooms wedged into a niche in the massive cliff face seemed wondrous to the Europeans who discovered it. Even to our eyes, with the early afternoon sun glinting off the wind-and-storm-shaped golden stone, it seemed almost miraculous.

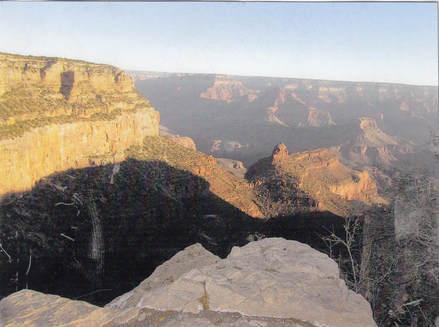

Grand Canyon National Park

Grand Canyon National Park "I love this," Sherrill murmured, as we watched light moving across the landscape, changing color from shades of orange to red.

We glanced into a few of the art galleries and shops that lined Sedona's streets and bought lunch in a restaurant with a view of the precipitous sandstone cliffs. Then we rejoined the group and drove through the deep gorge of Oak Creek Canyon, continuing to its much bigger cousin, the Grand Canyon. Back in 1967, on our way home to California from the Expo '67 World's Fair in Montreal, we'd stopped at the Grand Canyon for a couple of days, but hadn't been back since. This time, we stayed in a modern section of the lodge on the canyon's south rim, with our meals in historic El Tovar, a short walk along the rim.

The seven-thousand foot altitude made it difficult for Sherrill to explore for very long at once, but we did it in stages, resting whenever we felt like it. As the sun moved, changing the views of the canyons and rock formations in front of us, it almost seemed as if we were hiking along the rim, ourselves. We had the next day to explore on our own, taking a shuttle bus to specific lookout points.

"You don't have to stay," she'd tell me.

"I know."

Occasionally, when I returned from a walk I brought something to eat from one of the cafes or restaurants nearby. Best of all, we watched two Grand Canyon sunsets and two sunrises.

Monument Valley, Utah/Arizona

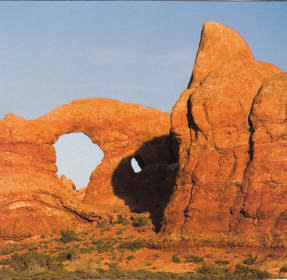

Monument Valley, Utah/Arizona Monument Valley, where John Ford filmed many now-classic western films, starting with Stagecoach in 1939, had long been high on our list of places to see. At last, we got there. Navajo guides took us in jeeps into the restricted backcountry of the Valley, now a Navajo Tribal Park, among the buttes, arches, and dramatic red sandstone formations. We'd brought masks to cover our noses and mouths, because the jeeps stirred up thick waves of orange dust as we careened over the meandering dirt roads. Even through a fine curtain of dust, the scene around us was more spectacular than we'd expected. This wasn't the first time that we felt as if we'd wandered into an old movie, but it was one of the most memorable.

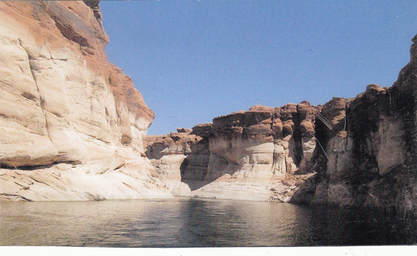

Antelope Canyon, Lake Powell

Antelope Canyon, Lake Powell Variegated red sandstone cliffs rose on both sides as Sherrill and I peered down into the reflecting blue waters toward the bottom of the drowned canyon. As spectacular and beautiful as the canyon we could see was, we saw that it plunged much deeper below the water. Slowly, our boat navigated the hairpin turns, sometimes the jagged cliffs above us almost touching. Other times, sunlight streamed through places where it looked as if a gigantic hand had scooped away fistfuls of the rust-colored rock. Shadows sank deep into the water, at one point even the moving shadow of our boat.

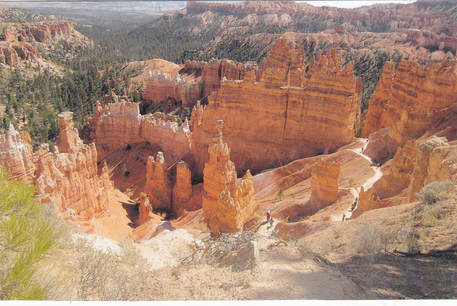

Bryce Canyon, Utah

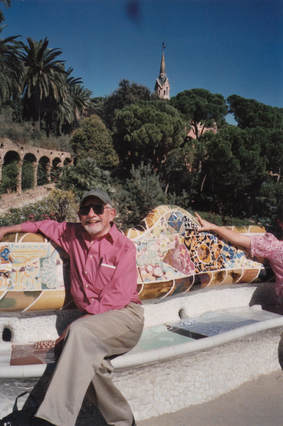

Bryce Canyon, Utah Kanab's other claim to fame was as the gateway to Bryce Canyon National Park, which was spectacular in a different way than the Grand Canyon. Actually, we learned, Bryce Canyon was not a canyon, but a collection of giant natural amphitheaters stretching side by side for more than 20 miles. Each of the amphitheaters reached out for 8, 10, or more, up to 18, miles of variegated sedimentary rocks, all of them crowded with eroded rock columns known as "hoodoos" or "fairy chimneys" that stood elbow to elbow like commuters on a train. Some of the columns stood as much as 200 feet tall, flaunting their red, orange, white, and pink stripes. I'd been there with my family when I was young, but this all was new to Sherrill, although we'd seen hoodoos in the Cappadocia area of central Turkey.

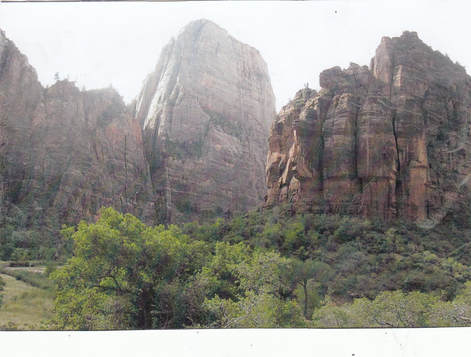

Zion National Park, Utah

Zion National Park, Utah Finally, to show her that I wasn't worried about her, I left her on the bench, gazing at the riot of red and orange hoodoos and explored farther afield, among family groups and couples who were taking each others' photographs with the hoodoos, brightly lit by the afternoon sun, stiffly posed behind them. A few times, I was afraid that a tourist taking a "selfie" was going to back up right off the side of the cliff.

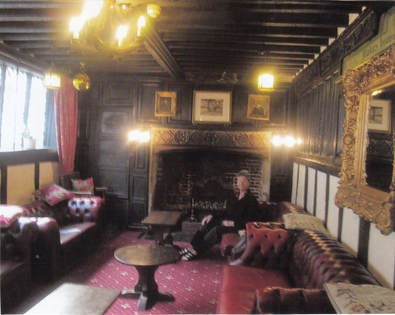

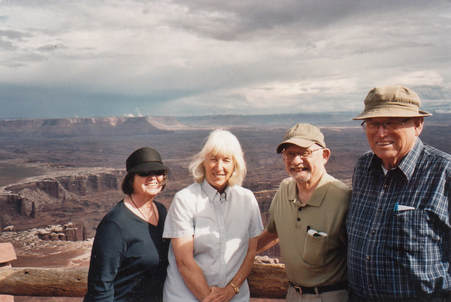

As often happened when we traveled with a group, Sherrill and I became friends with another couple during the tour, short as it was. Easy-going and fun to be with, they were from Oak Park, near Chicago, where Hemingway spent his youth. As it turned out, the wife also was a writer. After Sherrill and I returned home, I ordered her book, a tightly written historical novel that I enjoyed. When Sherrill felt up to socializing, the four of us had meals together. Other times, I ate with them and took food back to Sherrill in our room.

The Lodge where we stayed in Zion was perfectly located on the valley floor, surrounded by the massive ramparts of towering cliffs, and a short walk to the dining building. An elephant train took us around the valley, stopping at strategic points so that everyone, even those who didn't feel like hiking, could experience the spectacle of the enormous sandstone cliffs and rocky peaks. Later, while Sherrill rested in our room at the Lodge, I indulged in an independent walk, past the rock monoliths, cliffs, and streams.

"The Trump Hotel," our guide told us, "is the only hotel in Las Vegas without a casino. They weren't allowed to put one in because Mr. Trump had filed for bankruptcy."

Although some of buildings looked familiar, many of them were new to us.

This was the last trip that Sherrill and took together, but we had fifty-two years of exploring the world behind us, fifty-two years of turning to each other and asking, "What do you think of that?" Fifty-two years of sharing everything.

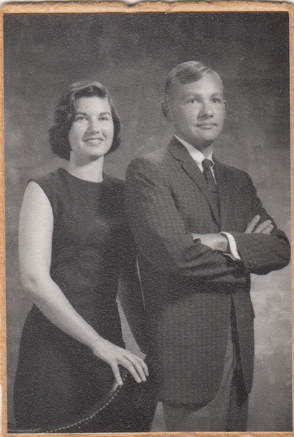

Sherrill and Bruce, 1965

____________________________________

Now, I'm developing the 81 blog posts about our

travels and life together during the 52 years

of our marriage into a book. I'll let you know

when it is published.

_____________________________________

RSS Feed

RSS Feed