Aleksander Nevsky church, Sophia, Bulgaria

Aleksander Nevsky church, Sophia, Bulgaria  Palm Sunday lighting of candles

Palm Sunday lighting of candles The next day was Palm Sunday in the Bulgarian Orthodox Church, which we and our friends acknowledged by dropping in at services in the multi-domed Alexander Nevsky cathedral that Sherrill and I had passed the afternoon before. The streets around it now were lined with people selling flowers that the faithful could take as offerings. In the dark cavern of the giant church, we found crowds of people, mostly women, lighting enough candles to illuminate all of Sophia.

St. Lazarus Day dancers

St. Lazarus Day dancers

Orthodox Church priest at Rila Monastery,

surrounded by frescoes.

Mountain village of Pirin "Mysterious Singers" welcoming us

Mountain village of Pirin "Mysterious Singers" welcoming us  Village men: no jobs, no place to go

Village men: no jobs, no place to go "Look at the men." Sherrill nodded at a row of old men sitting on benches in the village square near the river that cut through town.

She was right: the old men looked tired and bored and content to sit around complaining and gossiping while the old women tried to change what was happening to their village. As we traveled through the country, we saw this in other villages, too. Maybe the women would succeed, but it wouldn't be easy.

Ali and Carmela in Muslim village

Ali and Carmela in Muslim village "There's no work for us," Ali told us. "because we're old."

L., our new Bulgarian friend and guide, was translating. Ali and his wife were only in their fifties, but considered themselves old—and, to be honest, their hard lives had aged them prematurely.

We had driven much of the day on narrow mountain roads to this Muslim village in southern Bulgaria. The women all wore the traditional Muslim Pomak dress of pantaloon-like pants with long jacket, apron, and kerchief. Sherrill smiled at a local woman as they met on the narrow hillside street. The woman hesitated, looking confused by our appearance. They never saw foreigners in that village. L. stepped up, explaining who we were. Shy, but friendly, the woman invited us to her home nearby.

Carefully inching on muddy steps past a lean-to animal shelter, root cellar, and storage area, we entered a one-room house hanging on the cliff side. She asked us to sit on the two narrow beds against the walls and brought a bucket of goat's milk, which she poured into small glasses, and homemade feta cheese. Ali, her husband, joined us.

"Life is more difficult, now," L. translated for Ali.

At least, he said, under Communism they had jobs. He drove a tractor then and his wife worked in the tobacco industry. The switch to free market lost them their jobs and they couldn't find new ones. With their goats, growing vegetables, and producing some tobacco, they managed to earn only about 3000 lev a year, about $2000, and prices were higher, now. She also sewed and wove, making most of their clothes, as well as gifts, carriers for babies, and felt slippers to sell.

"Young people do better, Ali continued. "They have hope. Not old people like us."

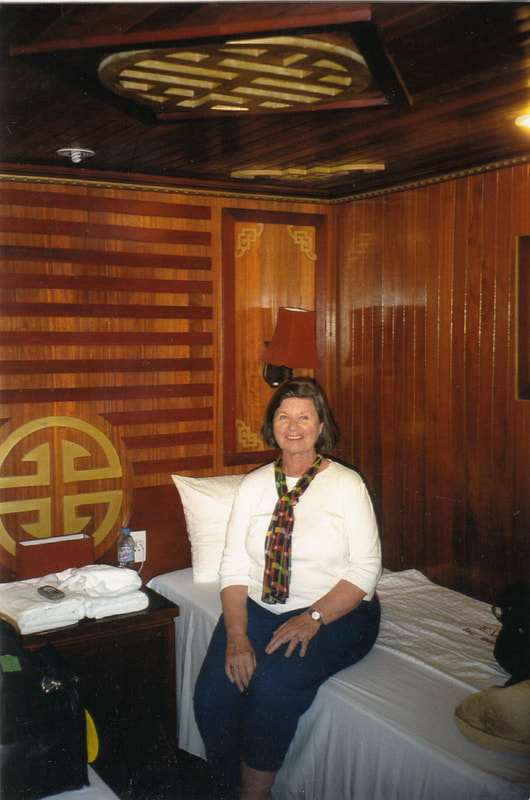

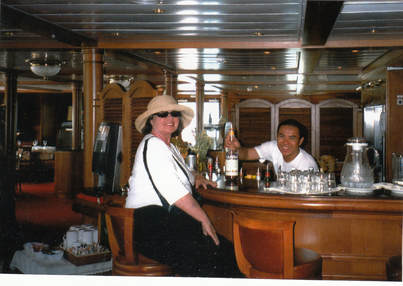

Sherrill in historic hotel, Plovdiv

Sherrill in historic hotel, Plovdiv "The Militia belongs to the people and the people belong to the Militia."

L. translated it for me from an old sign on a wall. An ominous message, attributed to Todor Zhivkov, the Party leader in Bulgaria,1954 to 1989.

Getting around the hilly city of Plovdiv with its streets of oversized cobblestones was difficult (even painful, as Sherrill discovered), but the old city was fascinating, especially the Ottoman mansions with their overhanging second and third floors, beautiful woodwork, and painted decorations. Once upon a time, before Communism, fine craftsmanship was appreciated. We also found, hiking along Plovdiv's hills, the remains of a Roman forum and amphitheatre. There seemed to be no place in Europe where they hadn't left their mark.

Villagers welcoming us, Easter Sunday

Villagers welcoming us, Easter Sunday  Roma villager with Easter lamb

Roma villager with Easter lamb And a feast it was: all homemade dishes prepared by the villagers, plus local wine and rakia—a homemade brandy popular all over Bulgaria, different in each region, but always lethal. About half way through the feast, which went on for hours, the songs started. Then the speeches between the songs: they made speeches, we made speeches, we toasted each other. They took photos of us, we took photos of them. We took photos of each other together. Everyone was enthusiastic and happy.

"We have the pony cart!"

It all was touching because they were completely sincere and happy that we were there, sharing the day with them. Nothing like this had ever happened in their village before. It was hard for any of us to get away.

Vocalizing village woman at

Easter Sunday feast

"See what you can do when you have a money and a staff?" Sherrill told me.

"You have me," I pouted.

"I know, sweetie." She patted me on the cheek.

Sherrill and 9th century frescoes in

Sveti Stefan church in eastern Bulgaria.

A UNESCO World Heritage Site

Part of women's exhibit, Rousse museum

Part of women's exhibit, Rousse museum  Village priest singing to us

Village priest singing to us  Sherrill in Royal train car, Rousse museum

Sherrill in Royal train car, Rousse museum To be continued....

If you find these posts interesting, why not explore the rest of my website, too? Just click on the buttons at the top of the page and discover where they take you -- including, a bio, information about my four novels, along with excerpts from them, and several complete short stories.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed